Review: Bitter Wheat (Garrick Theatre)

© Manuel Harlan

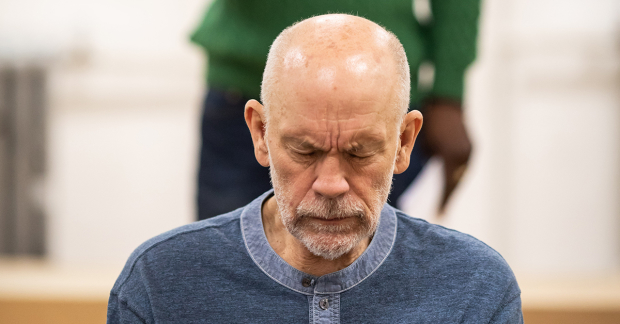

David Mamet has written some of the best and most provocative plays of the 20th century. And then he's written Bitter Wheat, which is not really a play at all but an unfocused and tawdry howl of anger which unforgivably wastes the talents of its greatest asset, its leading man John Malkovich.

Malkovich plays Barney Fein, a monstrous movie mogul who believes his greatest achievement is selling people sh*t and making them feel good watching it. He is puffed up with his own power, wealth and influence. Tackling a writer who stands up to him in the first scene, he sneers: "Use your words to wound me. I am going to cry all the way down to the helipad." He is a bully, a blackmailer, and a predator. He treats people like animals and is proud of it: "You pet them, you threaten them or you bribe them." He is also so fat that he can't lever himself out of a chair without great effort, and ascribes his behaviour to the fact that his fatness makes him rejected.

He is categorically not Harvey Weinstein and yet the play's entire first act, which culminates in his attempt to make a young starlet give him a blow job or watch him masturbate, seems to be based entirely on the testimony of the women who have levelled accusations at the disgraced movie producer, all of which Weinstein has denied. Oh, and it's also meant to be a farce, which means that in the second act, we tip into wilder territory about liberal values and the essential venality of all attempts at narrative.

There are, inevitably, because Mamet cannot write a dull play, some good lines – I particularly liked the idea that the producer has no idea he is on the board of the Metropolitan Museum. "Of art?" he asks, incredulously. But this is not Oleanna, or Speed the Plow, plays which harnessed an interest in power and human interaction to reveal bitter truths about academia and the rapaciousness of the movie industry.

All the playwright's fury with the film business, with liberal certainties – "I don't think you understand how much money I gave to the Democratic Party," Fein cries, wounded, mid-assault – is still in evidence, but he barely bothers to construct a structure in which to express it. The actress Yung Kim Li – who the running gag goes is brought up in Kent, though Fein insists on thinking of her as Korean – may fight back, but there is no sense of outrage on her behalf; the abuse is essentially a comic device. Fein is a pantomime villain, a buffoon rather than a real threat; when he traps her in his hotel room, he is disgusting rather than frightening. As directed by Mamet himself, the entire play lands on stage like an ugly lump of exactly the commodity Fein is so proud of selling to an unsuspecting public.

In the midst of all this, we have Malkovich, one of the most charismatic and dangerous actors of his generation. But, apart from a moment at the start of the second half, when the play takes an unexpected turn and he steps back from suicide, even his light seems dulled. He makes Fein truly repulsive, affecting a dull, threatening monotone of manipulation, wringing the best from lines such as "I could take this fucking footstool and make it a star". But even he seems becalmed by the play's sheer nothingness, its sense of thrashing around in search of a purpose. It feels symbolic that one of the biggest laughs of the night comes from the moment when he is lying on his back, waving his legs, beached like a whale.

As for Doon Mackichan, as the loyal, patient PA who acts as Fein's enabler and support, and Ioanna Kimbook making an impressive West End debut as the actress who is lured into his traps, they both do their best with virtually unplayable and criminally under-written roles. All the other characters are walk ons, there to allow a joke or two. It is shocking in all the wrong ways.