Review: Blackthorn (Summerhall, Edinburgh Festival)

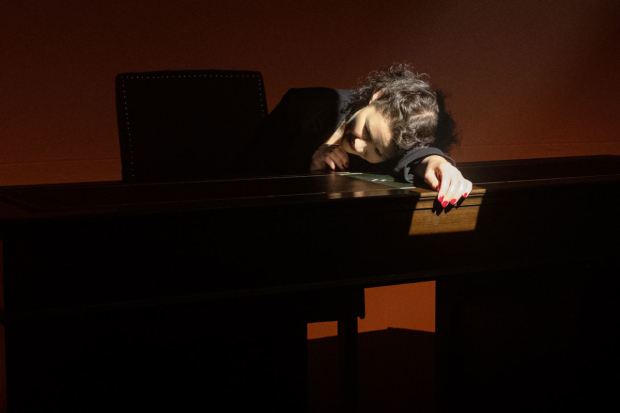

© Anthony Robling

Blackthorn – or sloe, as it's more commonly known – is beautiful when it comes into bloom. For one week a year, its thorny branches burst into white blossom. Its violet berries can be infused into gin. For farmers, however, it's a year-round "f***ing nuisance" – a rampant pest that's almost impossible to uproot.

In Charley Miles' tender debut, first seen at Leeds Playhouse in 2016, the plant offers a glimpse of a deepening rural divide: a lovely thing to look at, an irritant to live with. Blackthorn pits the harsh realities of country life against a countryside idyll as seen from afar.

The split's embodied by two lifelong friends, the first children born in a Yorkshire farming town for 20 years. One (Harry Egan) leaves school at 16 and lives his whole life locally. The other (Charlotte Bate) makes for London and university life. As the two of them loop in and out of love, differing circumstances see them drift apart. Skipping through that inconstant friendship, Blackthorn charts Britain's rural decline and it's urban rise: a widening chasm at the country's heart.

It's a slip of a play – two lives caught in snapshots at the points they entwine. As children, the pair play together in the fields. As teenagers, they test the possibilities of a relationship, only to end up, as adults, in different places, with different people and different points of view. But something always draws the two of them back to each other.

Despite a few loose ends, Blackthorn's keenly felt and delicately done. Miles tees up her oppositions with careful aplomb, nodding to motifs of change in The Cherry Orchard, and watching as two people who know each other inside out both change altogether even as they same the same. The land around them does much the same: still green, still pleasant, but harder and harder.

Jacqui Honess-Martin's bare-stage staging finds an eloquent fluidity in the way two bodies entwine, and carries big ideas in a bittersweet tale.