Absurd Person Singular

Alan Ayckbourn may have fallen out of love with the West End in recent years, but this triumphant restoration of his sardonic 1972 Christmas classic Absurd Person Singular shows just how much the West End needs him at the top of his game.

Director Alan Strachan is an Ayckbourn specialist, as he confirmed earlier this year with his meticulous revival of the lesser known How the Other Half Loves for the Peter Hall Company. But Absurd is something else: a knock-dead funny, brutally well constructed farce of drink, desolation and class warfare involving three couples in each others’ kitchens over three successive so-called festive seasons.

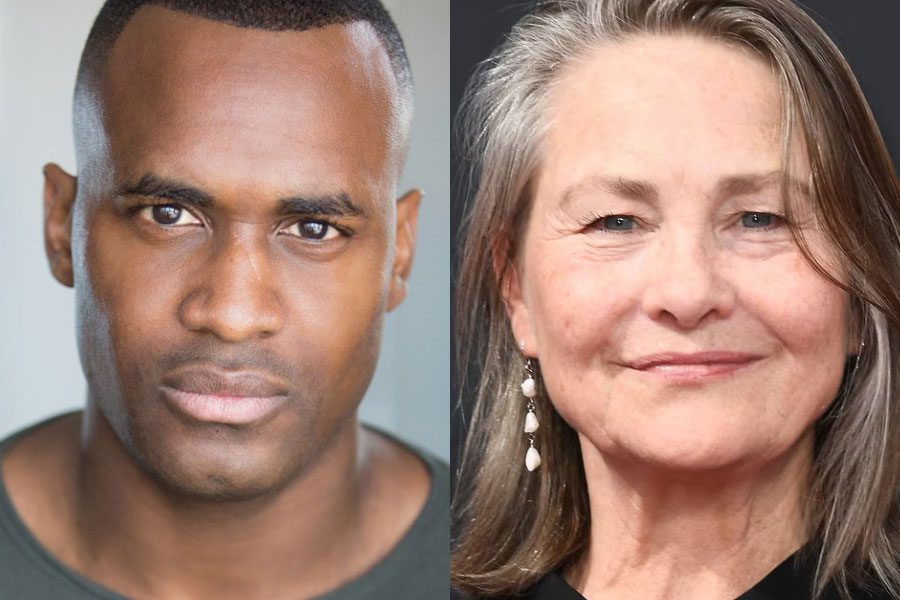

What I had forgotten was the extent to which the on-stage crises are perpetrated in a sort of backstage panic to the main event, the unseen cocktail party with the chatter rising each time the door opens and someone is ejected from the merriment. In the first act, the small businessman’s wife, Jane (brilliant, frenetic Jane Horrocks), is desperately cleaning down all surfaces (including her husband, David Bamber’s beaming Sidney) and searching for tonic water, a quest that involves a rain-drenched Outward Bound expedition in her own back garden.

In the second, the lizard-like architect Geoffrey (John Gordon Sinclair) is holding the fort – “What I lack in morals I make up in ethics” – while his zonked-out wife Eva (Lia Williams in a post-hippie frizzy hairstyle) tries to commit suicide by several means (Sabatier knife, gas oven, pills, light fitting flex). In the third, the company subsides into games-playing torpor while bank manager Sidney (David Horovitch) expatiates on “this woman business” and his wife Marion (Jenny Seagrove) settles into a gin-soaked immunity like some tragic remnant in Donizetti or Eugene O’Neill.

Seagrove doesn’t quite describe that extra dimension, but you can see where she’s going. None of the actors are playing for laughs, which is why they follow so thick and fast, Horovitch entering with a soaked trouser leg from a rogue soda siphon, or Horrocks and Bamber lying prone in a fit of misguided helpfulness, scrubbing the oven and seeing to the plumbing.

The rictus of hospitality conceals the power struggle of social hierarchy as a building development in the town involves all three couples in wheels and deals and financial misfortune manifest in the bleak midwinter of the third act. Here, the small business couple have risen like (and with) dough while the professional classes are in economic and spiritual retreat.

The action is retained firmly in the early 1970s, with Michael Pavelka’s design catching both the brave new world of fitted kitchen drawers and cupboards and the miseries of adapted Victorianism, and Brigid Guy’s costumes – shiny plastic dresses, floral patterns, flares and velveteen – providing a glorious period treat in themselves.

– Michael Coveney