Tis Pity She’s a Whore

The Actors Company bring Ford’s tale of incest and murder to this compact, bijou theatre. In many ways, it’s a strange choice of venue: the walls are bedecked with reminders of musical theatre, a stark contrast to the Italianate passion and villainy on stage.

Director, Tom Hunsinger has chosen to set it in a 50s Italy, tattered posters for I Vitelloni and La Dolce Vita hang on terracotta walls. It’s not a bad decision: it was a period notable for clashes between hedonism and austerity; between communism and the Catholic Church (and between the influences of two outside powers, the US and the USSR). Ford has a jaundiced view on Catholicism; the political influence of the clergy is a prominent theme of the play. But he also takes a strict moral line as he makes clear the consequences of licentiousness.

But the company fails to catch fire. When the Spanish henchman and assassin says to his master “Now you begin to turn Italian”, one wished it were true.

Like in many Jacobean tragedies the actors are propelled towards the inevitable bloody denouement by unwonted desires. Although Ford doesn’t have the subtleties of Shakespeare, the action moves briskly onwards. In many ways, it resembles Romeo and Juliet, although lacking the poetry of course. But the characters are far less complicated: pretty much everyone in the play is a nasty piece of work – which usually leads to some gripping scenes.

This all seems lost in this production. Too many actors chew over their words as if they were contemplating the merits of a cappuccino or an espresso after lunch.

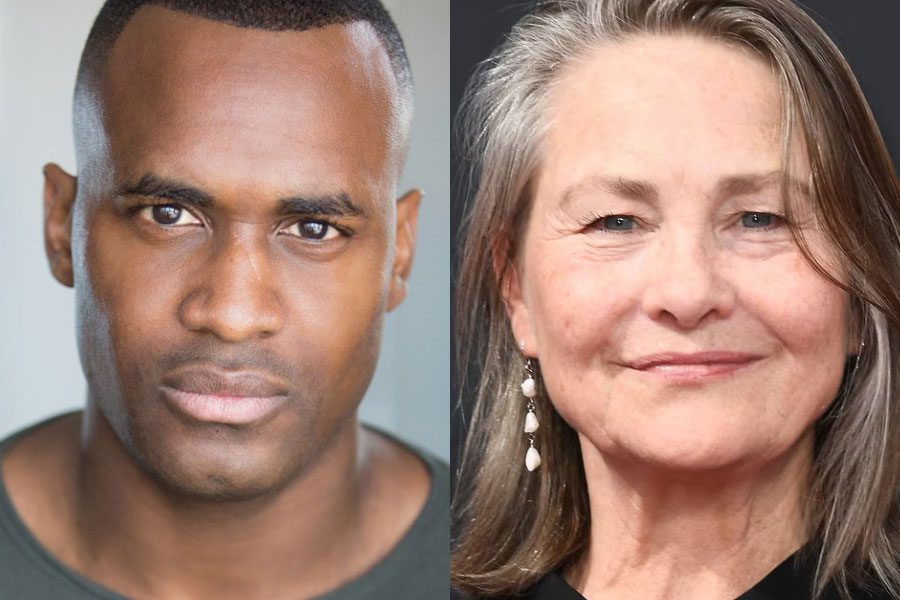

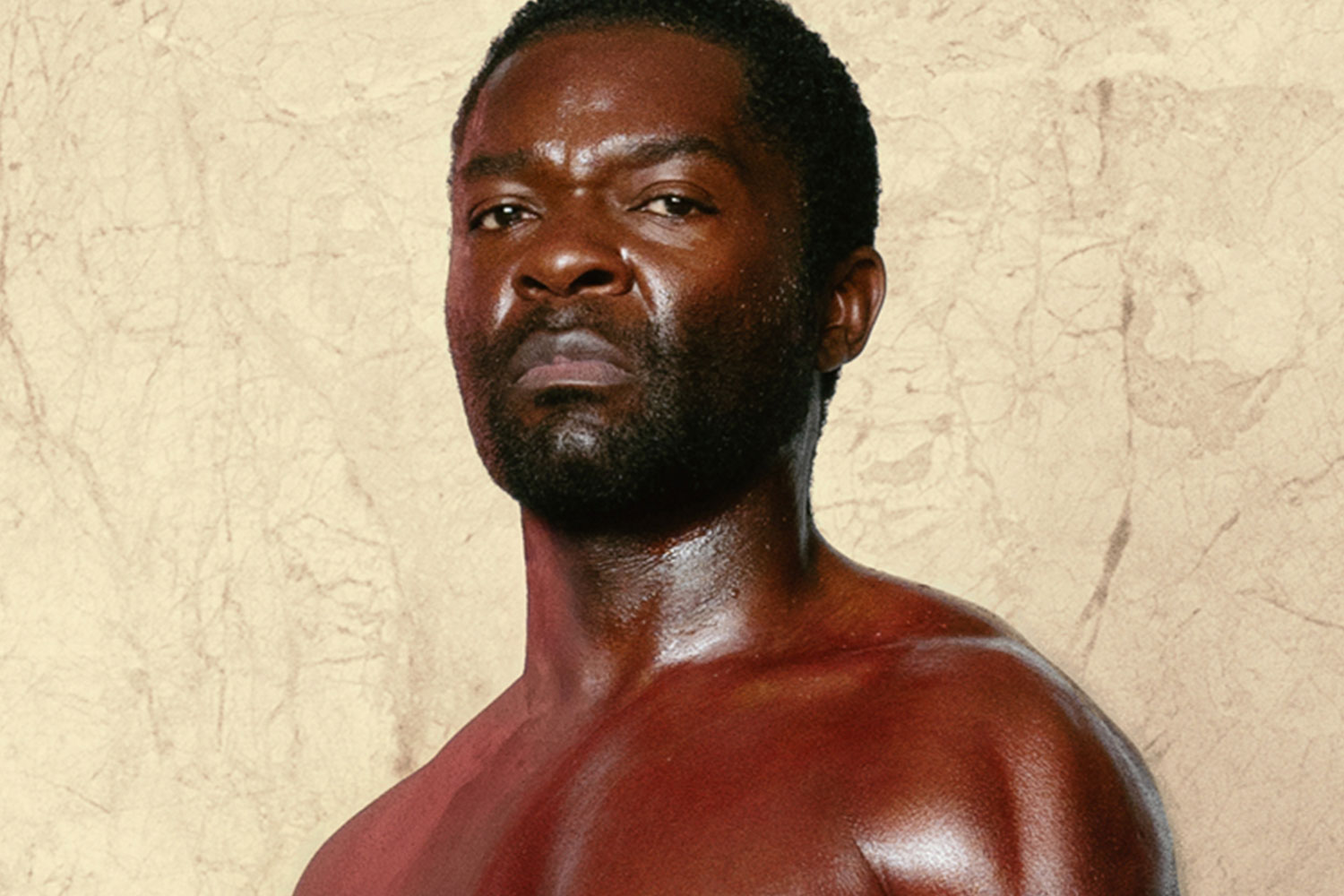

There’s an honourable exception in Lindsay McConville’s Anabella, the eponymous ‘whore’. She maintains a look of fragile innocence as events take their course. She’s particularly effective in the wedding scene; her white face, a mask of horror and disgust as she awaits her fate. Sadly, she’s not matched by her partner in incest, Daniel Tobin’s Giovanni who, until the final scenes, seems to be acting more like a sulky youth who’s had his iPod confiscated than as a lovelorn and guilty lover.

Remco Corman briefly entertains as a very camp Bergetto, the Mercutio character, and Brendan James is a Machiavellian cardinal, but the rest of the playing is rather one-dimensional.

This is a powerful story worthy of a Pasolini; instead we get a chamber melodrama; an Italian revenge drama as directed by Bergman, admirable in its way, but not a true tragedy. And that’s the true pity.