Glass Eels

Here we go again. Last time out in Comfort Me with Apples, Somerset

playwright Nell Leyshon gave us blight and decay in an orchard. This time,

it’s heat and arousal by a silt-ridden river where a teenage girl, Lily,

misses her drowned mother and hunts down a fellow old enough to be her

father.

Her real father is messing around with another woman and her grandfather, a

retired mortician, is bossing her about big time, demanding food and

scratching his groin as his underpants liquefy in the stifling temperature.

Nell Leyshon and director Lucy Bailey discovered early in their

collaboration that they both hailed from the same part of the cider county.

The trouble with their rural background is its dreary pessimism, heavy

symbolism and inbred, adolescent air of repressed sexuality.

A river runs through Lily’s dilapidated, darkly lit house, under its big

double bed and around grandpa’s work table. The kitchen, too, seems awash

with effluent, so dinner parties were never going to be much fun even if

they had them.

Lily, played with engaging gawkiness and attenuated limbs by Laura

Elphinstone, is gagging for sex and getting wetter with each passing scene.

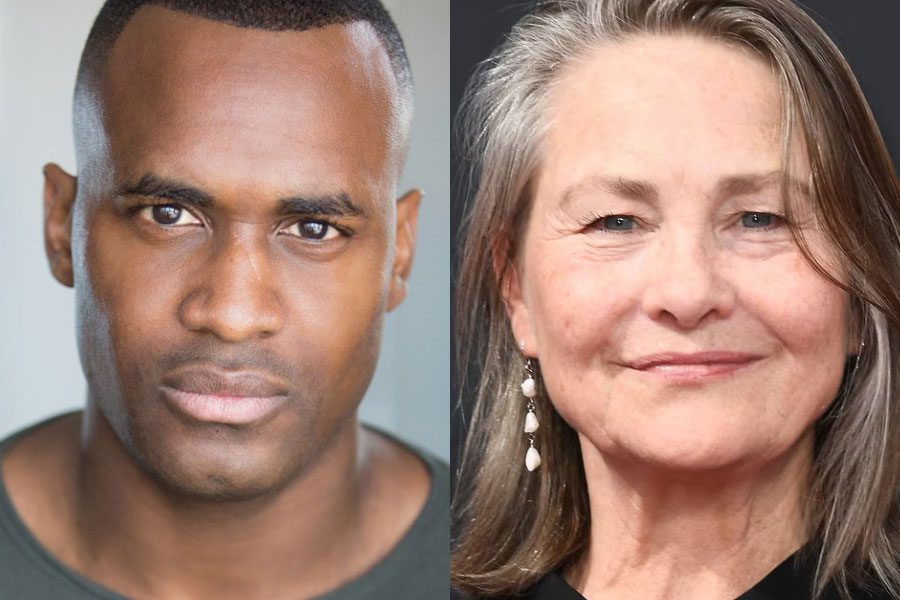

Yup, the play is that crude. Her dad Mervyn (Phillip Joseph), a terrible

bore with a fixed expression of total blankness, fondles a window frame. A

fly is trapped there.

Don’t tell me that fly is Lily. Okay, I won’t. Mike Britton‘s set is

dominated by a large, leaning glass – aha! – pane daubed with a child-like

cut-out sun. And in the river mud there wriggle and writhe a whole bunch of

eels, and what these slimy chappies represent you’ll simply have to work out

for yourselves.

At one point, grumpy grandpa Harold (Tom Georgeson) skins an eel, as

though he were – watch out for the metaphor – laying out a body on the slab.

Clunk! (I did warn you.) “Done this to enough women,” the old goat mutters,

“peel the stockings down. Them little cotton button things. Bit of thigh

above.”

The rest of the time, the characters — Diane Beck is dad’s fancy woman,

Tom Burke Lily’s reluctant lover — talk about going to the river,

smelling of the river and staying out late by the river until you wish

they’d all just go and jump in the ruddy river. I will concede this, though:

one man’s water torture is another man’s (or, more likely, woman’s)

atmospheric nirvana.

The Leyshon/Bailey connection is clearly devoted to its cause of moody,

maundering metaphysics but I much preferred their work together on Don’t

Look Now, where the script had more edge and bite and the water lapping

properties of sex and death in Venice more poignancy and narrative grip.

–Michael Coveney