The Late Middle Classes

There was a rumour, never confirmed, that “theatrical politics” kept Simon Gray’s The Late Middle Classes out of the West End ten years ago, linked to a snobbish assertion that a boy band musical (rather a good one, I recall) had replaced it on Shaftesbury Avenue.

So David Leveaux’s Donmar revival at least provides an overdue opportunity to test the critical suspicion that this might really be Gray’s lost great play. One always wants to be definite in these situations, but I find myself hovering. And the production is not totally persuasive, either.

A grown-up Holly, now a psychiatrist, returns from Australia to visit his old music teacher, Mr Brownlow, on Hayling Island. The grand piano swings round, and there is his younger self playing a bagatelle that Brownlow composed when he was his favourite pupil in the 1950s.

Mike Britton’s greenish set is a large wall-papered surface with outlines of doors and windows that never open. Young Holly, on the brink of adolescence, is trapped between the squabbling of his parents, Charles and Celia, and the refuge of Brownlow and his ageing, sherry-sipping mother.

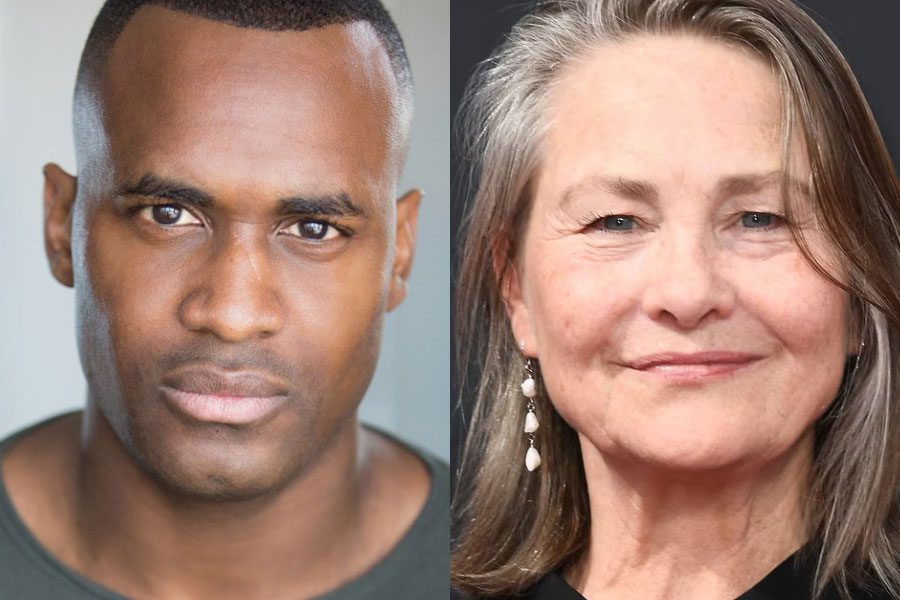

Charles is a staid pathologist, his wife a skittish, tennis-playing and vivacious woman who is suffering from a sort of post-war depression with rationing and the triviality of a provincial life. The role, first taken by Harriet Walter, is gloriously done here by Helen McCrory, switching between melodramatic gestures – she pretends to be dead, to attract attention – and bubbling, under-exploited vitality.

The play bristles with prejudice and suspicion over the relationship between Brownlow (Robert Glenister) and young Holly (Harvey Allpress is one of three boy actors, and chillingly impressive), which creates a marital rift blown open in the play’s best scene, an accusatory confrontation between Charles and Celia that is a poisoned well of mistrust and sorrow.

But none of the actors seem entirely at ease in their roles, a curious sensation. Peter Sullivan is a smoothly quizzical older Holly, but he’s one-dimensionally gruff as Charles. Eleanor Bron seems far too young to be Brownlow’s mother, but she suddenly turns from Viennese chatelaine to protective squaw with a vicious desperation.

We never quite know the truth about these people, but that is how life is, and at least Leveaux’s cast catches that resonating, flawed ambiguity. But the play still meanders too much, and the practical side of the music playing causes more problems than poetry.