Edge

Sylvia Plath and Ted Hughes were literature’s equivalent of Posh and Becks. The talented and beautiful golden couple who provoked both wonder and envy.

Of course, their mythological status only really waxed once a 30-year-old Plath – deserted by Hughes after two children and seven years of marriage – committed suicide in 1963, but it hasn’t waned since, even with Hughes’ own death in 1998. The newly released film, Ted and Sylvia, starring Daniel Craig and Gwyneth Paltrow, pays testimony to how enduring our fascination is with these two poets and their ill-fated love.

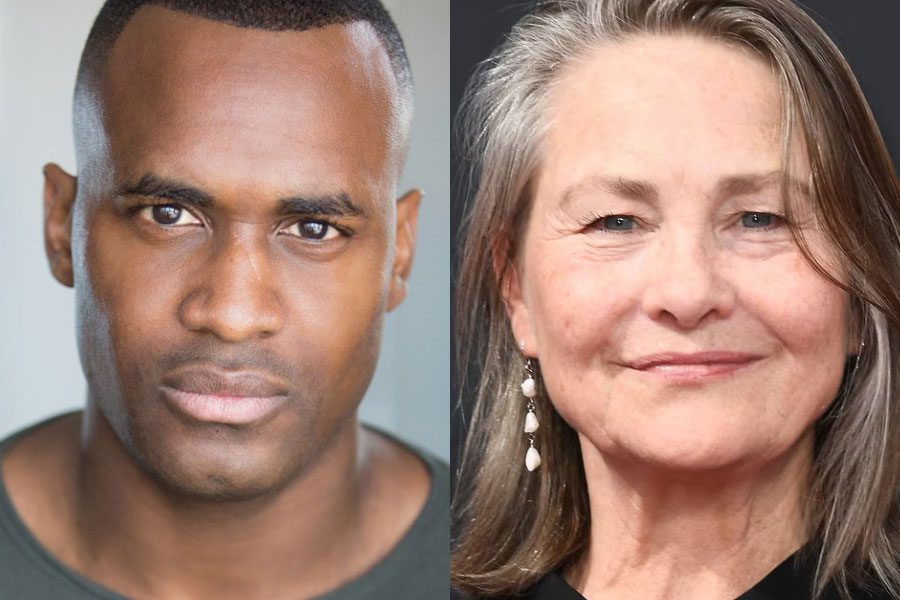

While there’s no competing with a Hollywood budget in the intimate staging of Edge at the King’s Head (or Hampstead’s New End, from where it’s just transferred), I find it hard to imagine how any amount spent on box office stars, locations, extras or period fixtures could offer a more searing insight into the tortured soul of Plath nor how any actress could ‘spill her blood’ in performance more wrenchingly than Angelica Torn.

“This will be the last day of my life,” Torn’s Plath begins, without a hint of remorse. Then, over the next two hours, she paces back and forth across the stage – dressed only with a chair, a desk and typewriter and a short stack of books and notepads in which she frantically scribbles – and across the years to explain how she arrived at this point.

Edge is written and directed by Paul Alexander, who has also authored a book about Plath, so it’s small wonder that the biographical details ring true. And yet – though Hughes, the ‘monster’, the ‘bastard’, the ‘black witch’, the betrayer’, is presented in a highly unflattering light – we’re in no doubt that Plath herself is not the most reliable of narrators, nor the most blameless of victims.

She admits to the addictive nature of her love and her hatred, and she recognises that, in marrying Ted, she was also embracing the ghost of her similarly cold and abusive father. ‘Not that I’m bitter, not that I’m vengeful, not that I’m a keeper of slights,’ she insists, letting us know just the opposite with a wry smirk.

This Plath is a thinker and so, as Voltaire would have it, life is a comedy, and we are in on the joke, even if, despite her pretence of being unfeeling, her own life ends in tragedy. A horrible waste that makes for harrowingly brilliant drama.

– Terri Paddock