Michael Coveney: Rylance rules the roost while Blanche is stranded

It was like old times for Mark Rylance on Saturday, as he dominated proceedings on the stage of the Apollo – scene of his Jerusalem triumph in the West End – with crowds thronging the pavement outside and leaping to their feet to acclaim a favourite son at the end of both Richard III and Twelfth Night.

And yet my guest, Anna Gruetzner-Robins, a professor of art at Reading University, Walter Sickert specialist and keen occasional theatre-goer, wasn’t quite sure who Mark Rylance was. His fame remains limited because he’s never had a hit television series, or a really big movie. Astonishing, but true.

Undaunted, I asked theatre owner Nica Burns if there were any plans to rename the Apollo the Rylance. She demurred, saying only that Rylance loved the theatre to bits, finding it very similar to the Royal Court with an extra circle, and relishing the company of the Apollo staff who are, said their owner, one big happy family.

Given that Saturday had been designated national Press day for some months, it was suprising how few critics took advantage of the two-play offer with a Shakespearean “feast” in between in the stalls bar.

Still, we happy few had a splendid day in one of the capital’s most beautiful theatres, surrounded by Rylance enthusiasts who included Richard Lambert, former FT editor and head of the CBI; Greta Scacchi; Stephen Fry’s partner Steven Webb; Linda “Baby Love” Hayden; and countless Shakespeare Globe regulars.

The interval “feast” was a decent game pie, a haunch of ham and a stilton cheese, which we enjoyed “to the lascivious pleasing of a lute” played by a musician from the acting company, poor fellow; you’d have thought he deserved a break without having to kowtow to a bunch of critics in his down time.

A quick check in the programme revealed our lutenist to be a Scandinavian, glorying in the name of Arngeir Hauksson, and proficient, also, in the theorbo (another kind of lute), the cittern (yet another Renaissance-style lute), the hurdy gurdy and drum. So, no flies on Arngeir, a fine specialist representative of Claire van Kampen‘s musical direction.

I particularly liked the very large recorders they play on stage, along with the sackbuts and cornettos. The amazing thing is that none of the music, nor indeed any aspect of the productions, sounds olde worlde or National Trust heritage (pace the Alan Bennett faction).

There is a wonderful freshness about these plays in the Shakespeare Globe performances, and I did sit there wondering where this now left the RSC, who seem to be struggling in the wake of the Globe (and indeed NT and Michael Grandage Shakespeares) to rid themselves of the shackling, conceptual interpretations that bypass the joy and spontaneity in Shakespeare, even in the tragedies.

Saturday was also the birthday of my guest Anna’s husband, the sociologist, writer and charity worker David Robins, who died five years ago. This added poignancy to the occasion, as he loved Shakespeare, and we left the theatre briefly to toast his memory around the corner in the ever welcoming Brasserie Zedel.

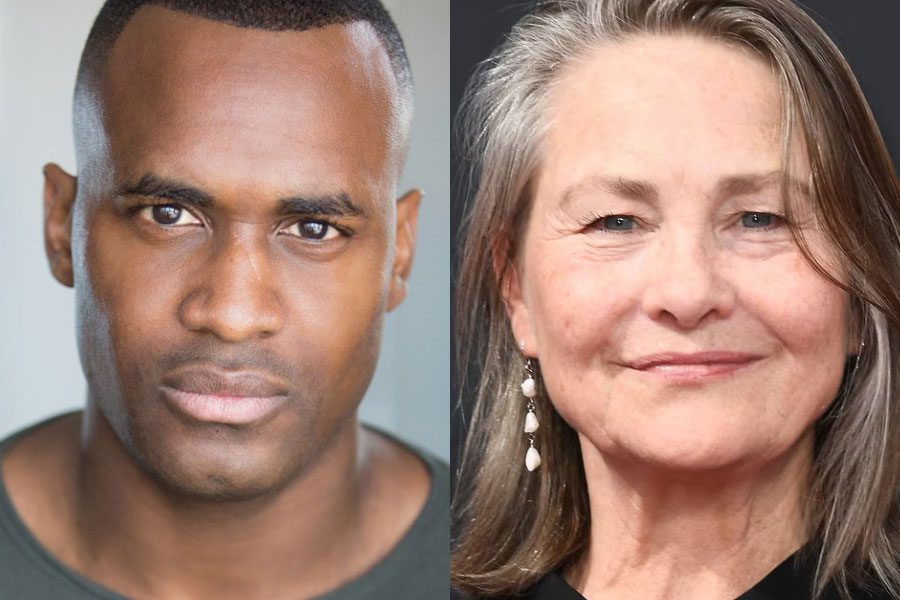

One surprising absentee from the Apollo was Blanche Marvin, indefatigable 87 year-old first-nighter and last week’s castaway on Desert Island Discs; perhaps she got stuck there or jumped aboard a slow boat to China by mistake.

Her choice of music was a bit disappointing, great stuff but hackneyed: Beethoven violin concerto, Shenandoah, the Liebestod from Tristan, Elgar’s Nimrod, Horowitz playing Mozart. And a song from Sondheim and Wheeler’s Sweeney Todd (“Not While I’m Around”).

Sondheim had “chanced to see,” he says, C G Bond’s Sweeney Todd play at the Theatre Royal, Stratford East, in 1973. We now learned that Blanche had co-produced that play with Joan Littlewood, saved the theatre and urged the adaptation on Sondheim, a series of heroic acts never mentioned before in any of the theatre’s histories, or indeed accounts of the musical.

I shall reassess her reputation immediately in the light of these revelations, though I was surprised to hear, later in the programme, that she’d told Peter Brook that he should support her fringe theatre awards because he himself had staged The Conference of the Birds in the Donmar Warehouse.

I’m not sure that’s true, though perhaps he rehearsed or “workshopped” it there if his own Bouffes du Nord in Paris (which had opened in 1974) had become suddenly unavailable before the show opened at the Avignon festival in 1979. I’d also missed that Blanche had “produced” on the fringe and had been with the Arts Council, so the programme was surprisingly and valuably informative.

One thing we did know was that Tennessee Williams had named Blanche DuBois for her in A Streetcar Named Desire. But I’d always thought this something you’d prefer to keep quite about, as the character has sad pretensions to virtue and culture and is a fading alcoholic with delusions of grandeur. Blanche herself, of course, couldn’t be more different. What’s in a name?