The Hard Problem (National Theatre, Dorfman)

For Tom Stoppard, the hard problem is the degree to which we can account for consciousness. For me, it’s writing this review. The Hard Problem is as slippery as a bar of soap with the water running; the play’s not so much beyond one’s grasp as never quite within it.

Stoppard’s first stage play for nine years is a parting gift to outgoing artistic director Nicholas Hytner and an unashamedly clever, not to say cerebral, not say "let’s check this out with the published script the minute we get out of here" kind of evening, which has always been the joy, and the difficulty, of the playwright.

I’m not sure that the acting is of a sufficiently subtle, idiosyncratic and lip-smacking quality to carry us through the narrative hoops and linguistic niceties of biology, philosophy, psychology and neuroscience pertaining to the story of a researcher, Hilary Matthews (Olivia Vinall), who has a buried past of – is it? – criminality and – yes, definitely – maternity in a research project at a luxuriously funded European brain science institute.

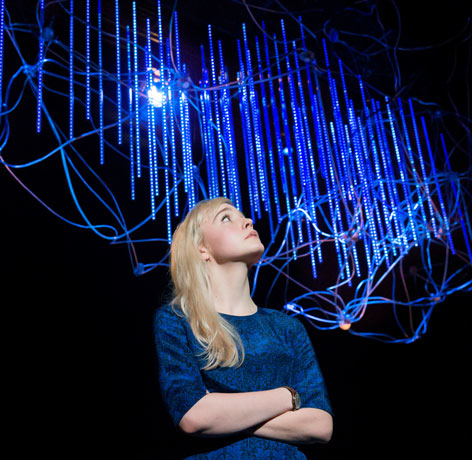

But there’s no doubt that in these agnostically quizzical times of angst about levels of consciousness and the "human" instincts of animals or computers, there’s no-one out there who’s not going to be intrigued by Stoppard’s tautly drawn drama, presented by Hytner and designer Bob Crowley beneath a spaghetti-like cranium of tubular veins that light up to the inter-scene playing of Bach’s preludes on the piano (sounds like Glenn Gould to me).

Bach shows how emotion forces its way through theoretical formulas, and Hilary’s other hard problem is one of intellectual conflict with her first mentor, and lover, transatlantic Spike (Damien Molony), her new boss Leo at the institute (Jonathan Coy) and the billionaire founder Jerry (Anthony Calf) who’s made his money in hedge-funds and has a recalcitrant daughter, hardly surprising as he only talks to her when fixing deals or firing people on the phone.

Stoppard’s last play for the National was a panoramic trilogy of Russian philosophy and revolution, The Coast of Utopia (2002), followed four years later by Rock ‘n’ Roll at the Royal Court, inspired by the Velvet Revolution in Prague and the music of the Rolling Stones and the Plastic People of the Universe. The physical, though not the philosophical, panorama is narrower here, the whole hilarious idea of a round table on consciousness in Venice summoned by a single gilt hotel bed rest. And every line – Stoppard never writes a duff one – is a point of view, or a diagnosis, or a theory.

The play spins cleverly, too, into Stoppard’s first look at unconventional sexual politics, with the partnership of Lucy Robinson‘s domineering Ursula and Rosie Hilal‘s Julia (an old friend of Hilary’s, and her Pilates instructor) muscling into the framework alongside Vera Chok‘s Bo, a conflicted guinea pig in yet another hard problem Hilary has, that of trying to understand other people’s minds when she doesn’t really understand her own.

And now, if you’ll excuse me, I’ll go back to the text, which I’ve already read twice – and Stoppard’s fascinating programme notes, which include a dialogue with Richard Dawkins and a low down on Cartesian dualities. The dancing girls are on hold.

The Hard Problem runs at the NT Dorfman