Why awards really do matter

Spare a thought for Dominic Cooke and John Tiffany today. At last night’s Evening Standard Awards, the two men were pipped to Best Director by Hollywood star John Malkovich. Tiffany had pulled together six spellbinding hours of Harry Potter. Cooke delivered a wonderfully rich, soulful August Wilson. Malkovich wasn’t even the best director in Kingston last year.

Every year, it’s harder to shake the suspicion that the Standards have enslaved themselves to celebrity. Malkovich’s win follows Nicole Kidman‘s last year; Helen Mirren‘s before that. In recent years, the process has shifted – an independent judging panel was swapped out for an advisory committee.

The price of the publicity is integrity. Every win that raises eyebrows undermines the rest

The Standard’s Awards are, of course, theirs to run as they wish and big name winners are inevitably good for the paper. They’re good for theatre, too. You’ll find London theatre splashed all over the front pages today, both in this country and around the world. That coverage will hinge off famous faces: Malkovich, Glenn Close and, er, David Attenborough.

The price of that publicity is integrity. Every win that raises eyebrows undermines the rest.

Awards matter. Not intrinsically – art isn’t a competition – but instrumentally. Rather than simply looking back, awards carry forward. I’ve previously made one case for their importance, namely that winners pass into the history books. Let me make another. Awards change the future.

An award is an asset – not just a recognition of success, but a testimony to it. They come with currency that can open up opportunities down the line. Talent plays its part of course, but a gong is a tangible thing. It reassures producers. It earns artists’ respect. It pulls in audiences. Awards are more than just statuettes. They are kitemarks and calling cards.

Giving awards involves conferring some status on an artist, and possibly, in the process, changing their career

When it comes to dishing them out then, judges have a certain power. The act involves conferring some status on an artist, and possibly, in the process, changing their career. Awards open doors.

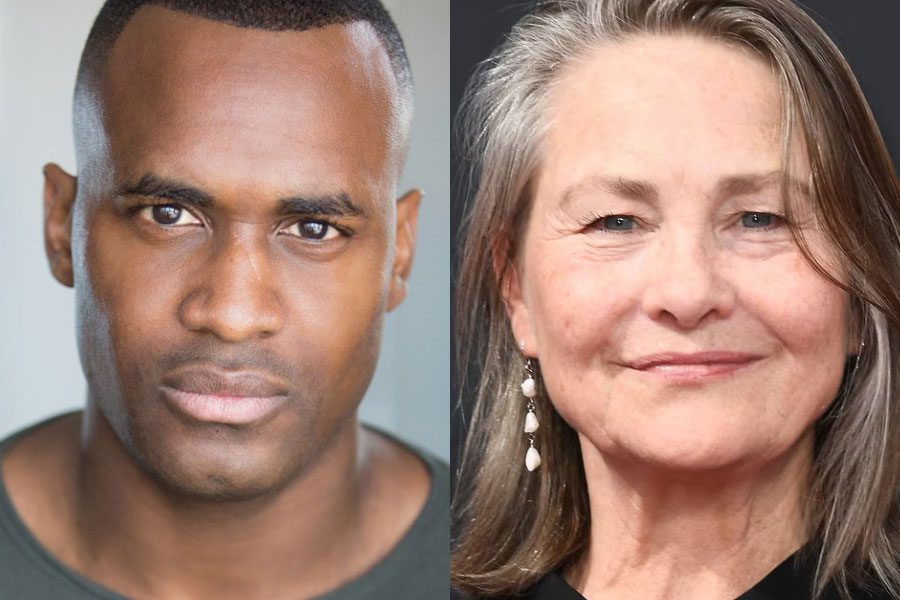

In a sense then, two awards at last night’s ceremony were more important than the rest: Tyrone Huntley‘s Emerging Talent Award for his performance in Jesus Christ Superstar, and Charlene James‘s win as Most Promising Playwright for Cuttin’ It.

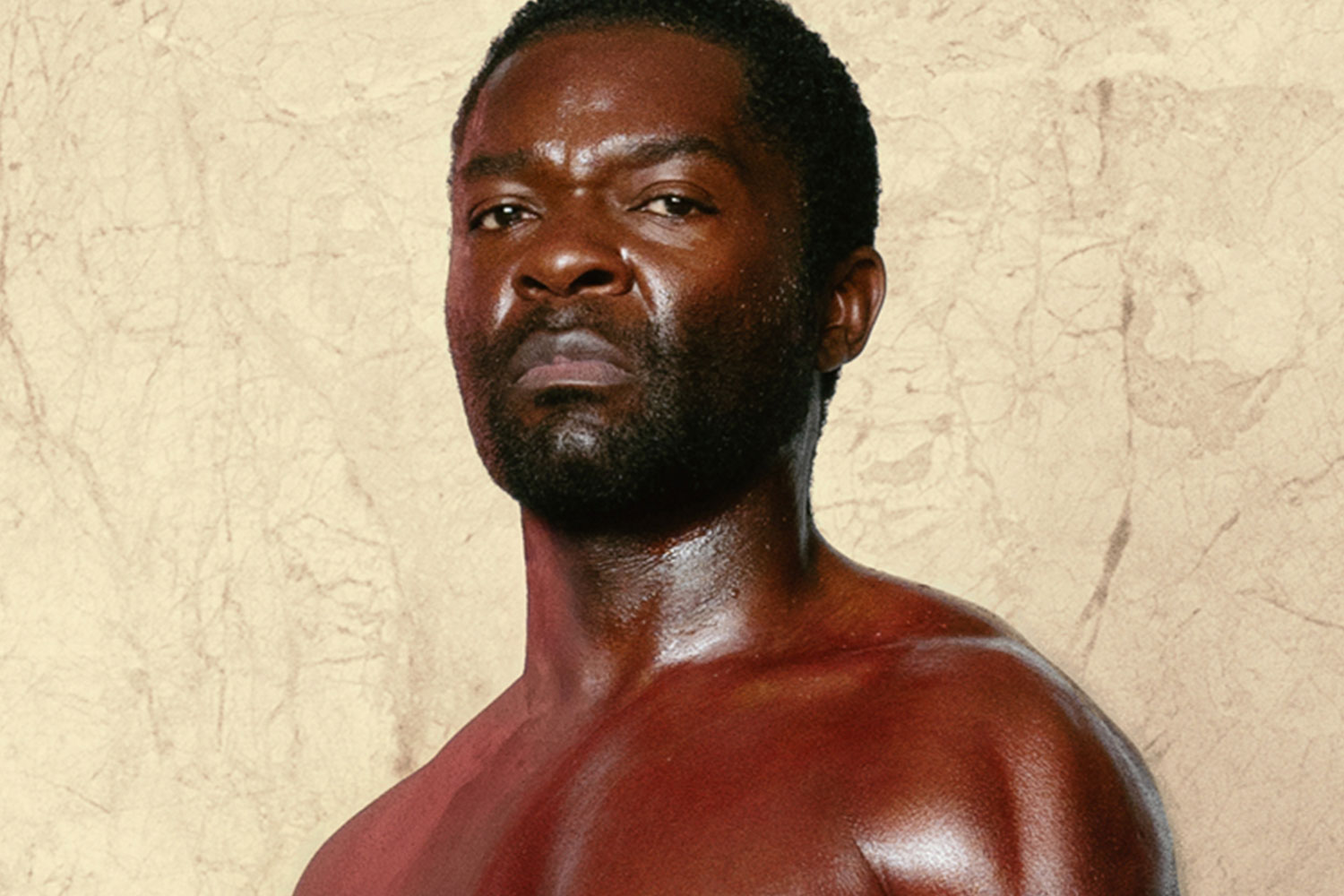

Both are thoroughly deserved. Huntley was a silky smooth Judas, a twitchy figure corroded by self-doubt with one hell of a singing voice, and James’ play took audiences right into the reality of a vital issue, Female Genital Mutilation, with both care and campaigning spirit. They will benefit from winning as others have before them. Look down the lists of winners and you find Chiwetel Ejiofor and Eve Best, Jez Butterworth and Kwame Kwei Armah. Awards didn’t make those artists’ careers, but they will have helped along the way.

Integrity matters, if not for its own sake, then because it preserves the currency of these early career awards. Without it, they can’t make a difference for artists and if they can’t do that, they count for nothing and if that happens, what's the point in the publicity?