Matt Trueman: WhatsOnStage Awards prove theatre is nothing without its fans

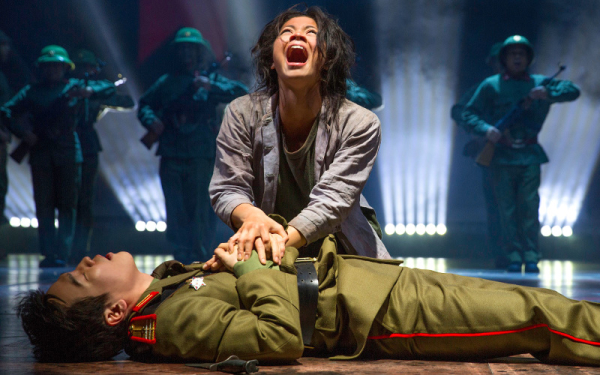

© Dan Wooller

It's easy to be cynical about the WhatsOnStage Awards. The biggest shows usually dominate: more people through the doors means more potential voters. You can spot some of the winners a mile off: those big-name vote pullers with their vast fanbases. And true, it would take an unhealthy theatre addiction (and a bottomless wallet) to be able to vote based on every single show.

That sort of cynicism misses the point entirely. Spectacularly. Stubbornly. Facepalmingly.

Because, frankly, isn't it absolutely brilliant that theatre – little old theatre – can still be a populist art-form? Audiences have more choice than ever before. Every movie ever made and every box set ever boxed is available at the click of a button, without your even having to get out of bed, let alone leave the house. Still theatregoers turn out in droves. Night after night. Week after week. Show after show. Doing so means buying a ticket, battling public transport just to get to the theatre, likely spending a few extras on food and drink en route, and then travelling home late at night on last trains and last buses. Theatregoing takes dedication and every vote that gets cast depends on that dedication. It wouldn't exist, either, if the shows weren't up to scratch.

Miss Saigon – last night's big winner with a record-shattering nine awards – draws more than 10,000 people every week. It opened last May. Almost half a million people and counting have seen Rachelle Ann Go and co. That's a lot of people. No wonder that producer Cameron Mackintosh turned up to accept Best Musical Revival and Best West End show himself, and seemed genuinely touched by the show of support. "I've always said the public knows best", he said.

NT Live has changed the game too. It's not just the long-runners that pick up the prizes these days. Vanessa Kirby – so sweltering as Stella in the Young Vic's Streetcar Named Desire – was named Best Supporting Actress because her performance was seen by audiences all around the world. The same goes for the Donmar Warehouse's Coriolanus, starring Tom Hiddleston and Mark Gatiss. It might have played to 250 people a night, benefitting from the brilliant, pin-drop intimacy of that boutique space, but it was beamed to tens of thousands in high definition. That's Shakespeare – and a difficult Shakespeare at that – as mass entertainment. Shakespeare winning a public vote: Best Revival.

Cynics might scoff that the big star names with their big worldwide fanbases inevitably pick up the acting prizes. The moment that Billie Piper and David Tennant were announced, Twitter's Whovians went crazy. Again, though, that's a big cause for celebration. Every former Doctor Who and every ex-assistant that steps onto a stage brings with them a raft of first-time theatregoers.

What's more, those fans are having an impact on the theatre that's getting made. They make it viable. They let producers take risks. Last night, the Menier Chocolate Factory's general manager Tom Siracusa told me that its current revival of Assassins – an infamously hard-sell, even by Stephen Sondheim's standards – was officially the fastest selling show in that theatre's history. Aaron Tveit, who was starring as John Wilkes Booth until filming commitments intervened, had been pulling audiences in from as far away as Japan. That's extraordinary, by anyone's standards.

Ultimately, I'm saying this: theatre is nothing without its fans. That's as true of the smallest shows as it is of the biggest. The Lyric Hammersmith's Secret Theatre ensemble has just opened the last of its productions and plenty of people have been sure to see every single one. Over the weekend, the blogger Megan Vaughan wrote a final paean to the company. It's criticism as fanmail. Other small-scale, off-beat shows have inspired similar outpourings of love – Christopher Brett Bailey's This Is How We Die, Alistair McDowall's Pomona, Three Kingdoms – and, thanks to the wildfire of social media, audiences attract audiences attract audiences.

The WhatsOnStage Awards might function thanks to economies of scale, whereby numbers trump ardor, but they celebrate the very thing that makes theatre possible: audiences. Without you – without us (the plural is key) – it doesn't make sense. More than that: it doesn't exist.