Benefactors (Sheffield)

In the programme Dan Rebellato cites the opening two lines and to a large extent they establish the style and tone of the play. “Basuto Road! I love the name!” says David, a successful architect. “Basuto Road. How I hate those sour grey words,” responds his wife Jane. But this is not just a difference of opinion; it’s a difference of time – he at the start of the Basuto Road project, she looking back on it – and by Act 2 he is echoing her words. Benefactors tells its story chronologically, but mixing action with narration and reflection both during and after the event, seamlessly knitted together, no joins visible.

The redevelopment project (not slum clearance, insists David) kills off his business and severely gores his marriage and friendships, largely owing to the consequences of David and Jane’s kindness towards the selfish bully Colin and his despised wife Sheila. In the early comic scenes we are within touching distance of sitcom-land, with the hopeless neighbours who eat the benefactors’ food, drink their wine, accept their lifts and let them look after their children. Soon the picture darkens as every good deed receives its due punishment.

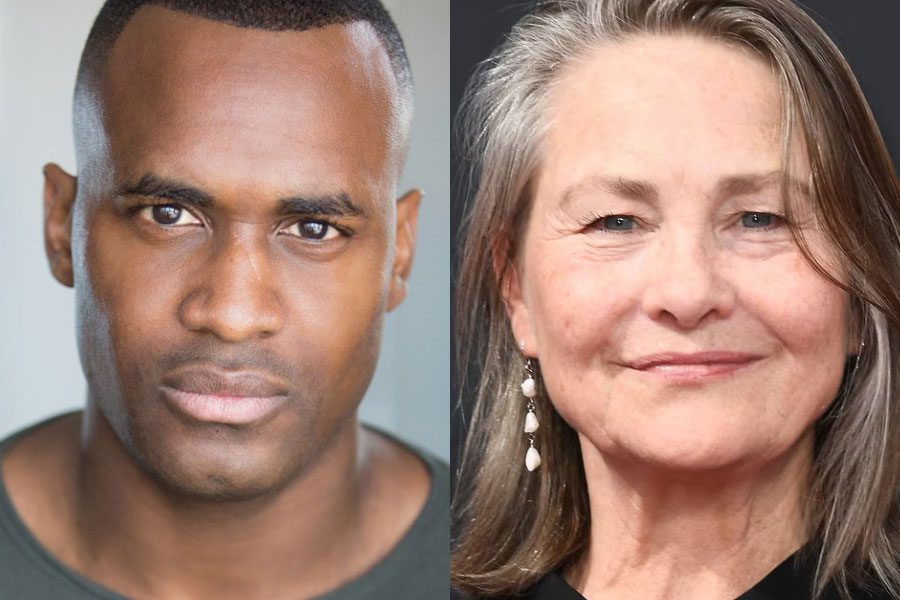

It’s an invigorating evening, with Charlotte Gwinner securing excellent performances from an ideally balanced cast. Simon Wilson (David) starts out with the puppyish enthusiasm of Richard Briers in a 1970s sitcom, becoming more rumpled and careworn as he fights to hold on to his idealism and innocence. Abigail Cruttendon, initially the “perfect wife” content to be an adjunct of the successful husband, plots the shifts in the balance of power subtly and skilfully. Rebecca Lacey’s Sheila, consumed with apologetic envy and admiration for David and Jane, personifies the power of helplessness and Andrew Woodall’s sneering underplaying gives the appalling Colin a hint of humanity. My only reservation about Gwinner’s production is that it takes too little account of the configuration of the theatre: mostly played square on to the audience in front of the stage, it doesn’t always serve the best interests of those in the side seats.