”The Beekeeper of Aleppo” at Nottingham Playhouse – review

© Manuel Harlan

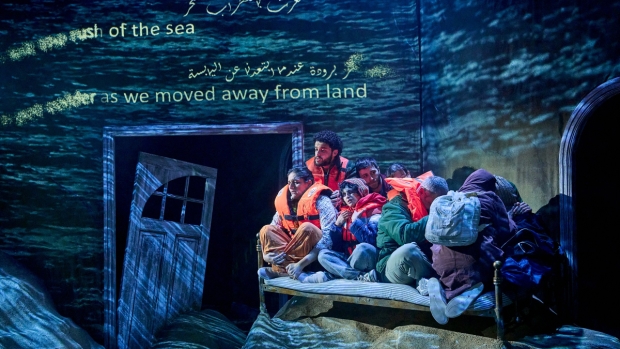

A home is stuck in the sands of time. In piles of dust, a hatch is a hiding place, an armchair is nestled and a single bed rests on top. They remain there throughout the piece as a reminder of what has been left behind and obstacles to overcome.

Nesrin Alrefaai and Matthew Spangler’s adaptation of Christy Lefteri’s best-selling novel follows a Syrian beekeeper Nuri (Alfred Clay) and his wife, Afra (Roxy Faridany), as they are forced to flee their home when war tears through Syria.

The Beekeeper of Aleppo opens with a booming interrogation voice at Heathrow as the couple seek asylum. As Nuri, Clay takes on the role of a narrator with instant warmth – but desperation lingers at the surface. Under Miranda Cromwell’s direction, the retelling of the couple’s journey from Syria, through Greece, and to the UK flicks back and forth in a way that is more jarring than drawing.

In flashbacks, we see the couple enjoying their past life in their adored Aleppo. Here, the sky is a gentle blue with soft blush clouds – a perfect backdrop for a social occasion with Uncle Mustafa (Joseph Long – who is a joy to watch). Conversation is easy; Afra’s art is impressing tourists, a teenage son won’t put down his mobile phone, and most importantly, their shared beekeeping business is bringing joy. It’s a slow scene of tranquillity, and one that we take for granted.

Soon, clouds turn to smoke and then to blots of blood. Film designer Ravi Deepres and light designer Ben Ormerod effectively transform the set by projecting bird’s-eye views of a war-torn city, inside of beehives, and feared choppy seas.

As Nuri’s narrative starts to blend and bend reality and nightmare, we rely more on Afra who has lost her eyesight at the helm of the horror witnessed. Faridany gives a considered and cautious performance that is at its strongest as she describes her reliance on other senses – the desire to taste pistachios, to smell kebabs and to touch fine silk. Tingying Dong’s sound design adds soothing buzzing and breezes and an acoustic traditional score feels authentic, but it is a shame that the sound is so delicate. I only wish we experienced more intensity to immerse in this heightened sense.

On stage, the grief is quiet but profound and particularly striking following current news of the earthquake devastation in Turkey and surrounding countries.

Influenced by her time working with refugees, Lefteri has crafted unforgettable characters and writer Matthew Spangler has given them free-flowing dialogue that really brings light to the story. A mighty ensemble cast shapeshift as the people that Nuri and Afra meet: particular heart-warmers are a Moroccan refugee with a new taste for tea with milk and a friendly Somalian woman who hums gently despite her pain. Their presence contrasts with tick-box concerned Western volunteers, selfish smugglers, and ignorant civil servants who draw scoffs rather than laughs.

The script is clever and candid; Nuri and Mustafa exchange emails that share the depth of their guilty consciences as fathers, whilst repeated motifs of the unconditional care the two gives to bees highlight the different treatment that they receive. On stage, the mirage appearances of the young and quick-witted Mohammed – Elham Mahyoub’s portrayal is a triumph – both heal the heart before shattering it over and over.

The Beekeper of Aleppo is wonderfully written and performed, but with a story so sharp the production needs a bit of a grit and could afford to have more sting.