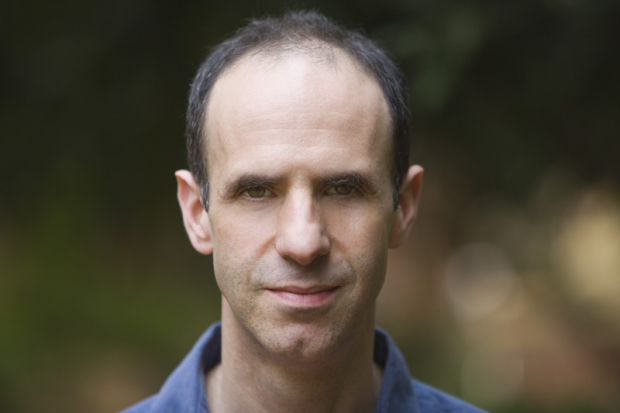

Tim Supple: 'I’m envious of people who can root themselves'

The itinerant director is back home in Britain to stage the new Grange Festival’s first opera

Once a ubiquitous figure in British theatre, nowadays Tim Supple is conspicuous by his rarity value. His absence doesn’t mean he’s been inactive, however. Like a latter-day Peter Brook, the director has spent much of the past two decades plying his craft overseas. He is currently two years into an ambitious long-term project with Dash Arts to explore Shakespeare’s King Lear through research and production across five continents.

Now back on home soil to direct Monteverdi’s opera Il ritorno d’Ulisse in patria, the inaugural production of The Grange Festival in Hampshire (previously the home of Grange Park Opera, ex-tenants who have confusingly relocated under that same name to the West Horsley estate in Surrey), Supple took time out from his lunch break on day one of rehearsals to talk to WhatsOnStage.

What is the difference in approach between directing a play and an opera?

It’s something I’ve thought about a lot. At heart it’s all theatre – telling a story, bringing characters and situations to life – so the fundamental principles are the same. But with opera the music determines so much.

One of the most enigmatic and interesting things for a director in Shakespeare, for example, is trying to work out the rhythm and shape of a scene. In opera the music does that. In fact it does more than that: it dominates the concentration and physicality of the singer.

Stanislavski evolved his method of acting through watching opera singers, because what he saw in them was an absolutely clear focus that was given to them through the music, and he felt that the acting of his time lacked that clarity of intention. So I’m very aware that spiritually it’s a brother-sister relationship between theatre and opera.

A frustrating one?

It can be, of course.

That may be because you’re a very organic director. There’s a free flow to your work.

Yes, I do think that. I ask myself the same question but I think it’s mostly structural – to do with the industry, not the form. If I could work in opera the same way I work in theatre, bringing people together in a different way over a longer time period – and if I could work experimentally and organically – I think the two would be far, far closer. But in the opera profession time is short and people’s ability to commit to a project is limited because they have other things to do.

What I do find frustrating is when habits of professional process are turned into immovable facts. For example, opera hours tend to be 10.30 to 1.30, then 2.30 to 5.30. That’s all quite strict and I respect it, but it’s quite different from the way I work when I’m in a freer situation.

Is this production of Monteverdi’s Il ritorno d’Ulisse in patria influenced by your work in Asia and elsewhere?

Inevitably it’s influenced by what I’ve learnt in India and in Arabic countries, and what I’m learning through other international research projects in post-Soviet countries.

What drives you to look abroad? Is it frustration with what’s at home or a thirst for new things?

Mainly the latter, though it’s sometimes prompted by the former. I think it’s very important not to be thoughtlessly wooed by the idea that other systems are that much better. Both in Britain and abroad people knock their own culture of theatre because the grass looks greener elsewhere. And of course there are things that are done better in other countries, or outside conventional theatre or in folk theatre.

In some ways I’m envious of people who can root themselves into their situation. In Moscow there’s a lack of desire to go elsewhere, and that’s rooted in a lifetime spent doing what they do and just getting it right. It’s a healthy attitude, but I don’t have that.

Would you ever consider taking all these experiences and running a theatre in this country?

I’d like to very much. Ever since I travelled to India I’ve knocked on doors with the idea of establishing a genuinely international theatre environment in the UK. I’ve been having these discussions for ten years. And it’s not off the table.

When you brought your Indian A Midsummer Night’s Dream to the Roundhouse ten years ago, was that a challenge to this country to shake itself up?

Bringing that show here was about my delight in those performers and the desire that people see the show. At that time I was trying to kick a door open at the RSC and see if I could help them establish an international aspect to their work alongside what Michael Boyd [then artistic director] was doing with visiting companies. It didn’t happen.

Yours is going to be the first new production by The Grange Festival, a new company. Have you had complete artistic freedom?

Michael Chance, the artistic director, has been fantastically open. The brief was to make a very strong piece of music theatre and do something special. Nothing else.

Il ritorno d’Ulisse in patria is a very early opera. Does that allow you more freedom to treat it as a blank canvas?

I’m not sure if it’s any easier to treat as a blank canvas than an opera by Mozart, say. If it is open to interpretation it might be to do with the spare nature of the music, but it might be to do with the mythic story.

It begins with an archetypal prologue, then tells a brilliantly adapted version of Homer. The balance of drama to music is more powerful than in many other operas, and you have to animate it with sensitivity and vividness.

In telling old stories we’re trying to touch the essence that has been true across the centuries. So while the production has to have a modern sensibility, it also has to reach back into the roots of time and theatre. That’s what we’re trying to do.

Il ritorno d'Ulisse in patria opens at The Grange Festival on 7 June. It runs in repertory until 7 July.