The Tempest at the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse at Shakespeare’s Globe – review

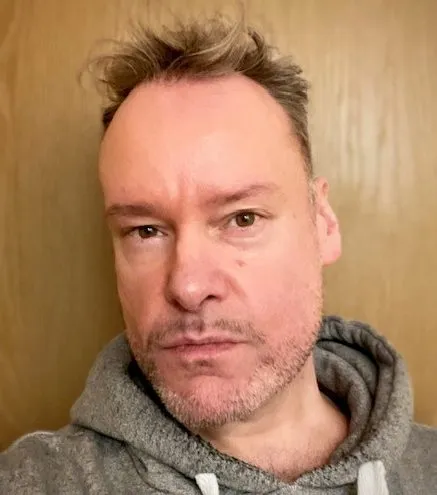

The production marks Tim Crouch’s directorial debut at the Globe and he also stars as Prospero

This is Tim Crouch’s Tempest as much as it is Shakespeare’s. Admittedly, for anybody unfamiliar with this most fantastical of the Bard’s late romances, it probably isn’t an ideal introduction, but theatrical iconoclast Crouch breathes bracing new life into a frequently produced play.

Gone is the storm, and the magic practised by deposed Duke Prospero (played by Crouch himself) and his spirit servant Ariel (not the usual ethereal figure here, but a stoic, middle-aged, female-presenting eccentric, possibly a shaman, portrayed with vinegary authority by a compelling Naomi Wirthner, knitting away on the sidelines while the stories unfold). Prospero’s, or rather Caliban’s, island is no tropical paradise, nor is it the sci-fi-adjacent lunar landscape depicted in Jamie Lloyd’s Drury Lane version in 2024. Instead, Crouch and designer Rachana Jadhav seem to have conceived it as a sort of Polynesian-flavoured curiosity shop, with artefacts, tin cans, dusty old books, giant masks, pulleys, mirrors, angel wings, candles, all jostling for attention. It’s a ramshackle, rather beautiful eye-full, offset by modern dress costumes that range from pedestrian through hipsterish to appealingly bizarre.

This version is less about Prospero seeking vengeance on his usurping sibling (usually Antonio, but here Antonia, gleefully played as an upper-crust villain by Amanda Hadingue) and watching as his daughter Miranda falls in love with shipwrecked Ferdinand, the first young man she has ever clapped eyes on. Rather, it’s about the very act of bearing witness, and the ritualistic, incantatory practise of the same tale being told time and time again.

In Crouch’s vision, Prospero, Miranda, Ariel and Caliban are the four storytellers, fated (or doomed?) to recount the plot and action of The Tempest apparently ad infinitum. Lengthy speeches usually delivered only by Prospero are divided amongst the quartet, suggesting that the power and emphasis of a story changes according to who’s telling it, and much of the text is re-ordered and embellished. Orlando Gough’s score – an esoteric, genre-defying mix of world music, contemporary classical and what sounds like modern jazz, potently sung by Emma Bonnici and Victoria Couper – runs through the evening like hypnosis and a taunting.

Crouch’s signature preoccupation with blurring the boundaries between audience and actors gets an enthusiastic outing, with all other characters – the Neapolitan king Alonso, his drunken servants Trinculo and Stephano, the kindly advisor Gonzalo – plucked out of the Wanamaker’s auditorium. It’s fun and a little unsettling, although the clambering over sections of the audience gets a bit repetitive. It would be a shame to give the game away, but the reveal and subsequent employment of young love interest Ferdinand (a winning Joshua Griffin) is a stroke of meta-theatrical genius.

Not all the humour lands and some of the acting is pretty coarse; it’s unclear whether that’s deliberate, given that more than half of the dramatis personae are supposed to be audience members dragged up on stage, but it does mean that a lot of the comic business becomes excruciatingly annoying. Having Patricia Rodriguez’s overbearing Stephano and Mercè Ribot’s cowed Trinculo rampaging drunkenly all over the theatre is probably more fun for the actors than it is for the audience. Shorn of a lot of his lines and some of his authority, Crouch is a low-key, mercurial Prospero, but it’s a performance that lingers in the memory. Jo Stone-Fewings delivers fine work as Alonso and is genuinely touching when reunited with his long-lost son.

Even more moving is Sophie Steer’s Miranda, a gawky, forthright wild child, blissfully unaware of the world beyond the “island” she has always inhabited. Steer gives her an open-faced emotionalism and physical restlessness that boils over into utter joy when she encounters Ferdinand, then realises the sheer scope of humanity beyond her limited experience. Faizal Abdullah’s Caliban is another unconventional take; he’s not the crude monster often presented, but a taciturn, sensitive, Malay-speaking lad in a dirty football T-shirt and flip-flops, his life rhythm markedly different from the European interlopers on his island. There’s a sense of kinship between this Caliban and Ariel that tears at the heart.

Equal parts haunting and frustrating, sinister and unpredictable, this is a challenging treatment of a familiar play. It won’t be for everyone – a concession Crouch even builds into the production in a particularly funny moment near the end – but chances are you’ll be discussing it or thinking about it long after the performance is over. As a testament to the power of storytelling, it’s a considerable success.