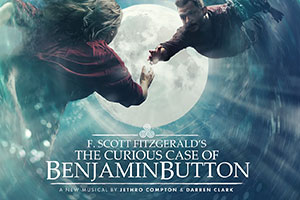

The Curious Case of Benjamin Button review – an unqualified triumph of a musical

The show returns after a critically lauded run in 2019

Is this the most emotionally devastating British musical since Blood Brothers? The audience reaction the night I saw The Curious Case of Benjamin Button suggests that it might be, the entire house spontaneously yanked out of their seats on the last beat of music, openly weeping but cheering with joy. It dresses up a bleak but universal meditation on mortality, love and loss in a bizarre yet compelling central premise and thrilling, swoon-worthy music: I don’t think even Standing At The Sky’s Edge gives its patrons this much of a richly enjoyable emotional battering. Watching this intelligently expanded and substantially reworked version of a piece that was already a winner in its original 2019 iteration, feels like encountering a beloved friend after years apart and noticing that they have grown even more beautiful with time.

Time, its measurement and the way it impacts on our lives is a major preoccupation of Jethro Compton and Darren Clark’s musicalisation of the F Scott Fitzgerald short story about a man born 70 years old who ages backwards to infancy. The title is probably best known from the 2008 Brad Pitt movie, but script writer, co-lyricist, designer and director (because, apparently, you can never have enough strings to your bow) Compton transplants a story preposterous on paper but riveting once you’re under the spell of the show, to his native Cornwall and setting it between the early 20th century and the 1980s.

In response, songwriter Clark provides a score that shifts and shimmers from delicate to thunderous as it encompasses folk ballads of aching longing, fishermen’s shanties, and rousing mineworkers’ chorales that thrill the blood. In fact, since a team of five actor-musicians has now more than doubled to a dozen, it’s musically even richer than before, a particular gain being complex new instrumental sequences and multiple-part harmonies that make the hairs on the back of your neck stand up. There’s even an anthem sung in Kernewek, the ancient Cornish language. Clark’s musical arrangements have been significantly upgraded, employing a combination of percussion, drums, strings, brass and guitars, and have a similar drive and sense of melancholic exhilaration as Once, Come From Away and the soon-to-return Hadestown. It sounds meatier now, more excitingly percussive. The tunes are memorable, haunting even, and surge through the theatre like a tsunami of feeling.

The main feeling generated by the cumulative effect of inspirational musicianship, magnificent acting performances, a heartrending story leavened with humour and stage magic by the bucketload, is total euphoria, even as you’re wiping the tears off your face. The tone is pitched somewhere between the mystical and the downright wacky, that proves entirely bewitching. The rollicking humour of so much of it throws the moving elements into profound relief.

Compton directs with a surface simplicity that belies some serious mastery of his craft. Relationships are convincingly, clearly established within clarity and economy, and locations are conjured up by little more than a couple of planks, upturned boxes and a change of light but are never less than vivid, while the cast of prodigious multi-talents swap character in the blink of an eye. We see Button travel backwards through service in World War Two and a subsequent blissful family life, watching the historic moon landings on TV, to nursing his beloved wife at her death aged 61 while he gets ever more youthful. Potential mawkishness is mostly kept at bay by wit and the sheer invention and ingenuity of the theatrical storytelling. What could feel excessively whimsical acquires an emotional urgency that proves overwhelming as the story hurtles towards its inevitable conclusion: our hero as a babe in arms unable to recall his tumultuous life except as a series of vague dreams. Fantastical as the story is, it deals with love, mortality and the passage of time in a way that is at once relatable and thought-provoking, and the overriding message – to make the most of the life we’ve been given – has seldom felt more pertinent.

As with Operation Mincemeat, first seen on the fringe at around the same time and now a sensational commercial hit, The Curious Case of Benjamin Button has had money and rigorous artistry lavished upon it, so that it now looks entirely match fit for the West End and maybe even Broadway. However, it feels very special to experience it in Southwark Playhouse’s intimate new theatre.

In all honesty, it’s hard to tell whether this is “better” than the pre-pandemic Benjamin Button as that was a perfect miniature musical, with a soaring score and a heart as big as the moon that is a recurring motif in the text, but the production values are considerably higher. It now has a choreographer (Chi-San Howard) who provides swirling, swaying, stomping dances that are even more remarkable for being executed by a cast simultaneously playing a multitude of instruments. Compton’s set is a lovely, atmospheric jumble of fishing nets, buoys, staircases, trapdoors, corrugated iron and good honest wood, complemented by Zoe Spurr’s gorgeous lighting, while Anna Kelsey’s distressed-but-expensive looking costumes are the epitome of shabby chic. The only problem is that Luke Swaffield’s sound design, while honouring the alchemy of voices, band and some stunning aural effects, occasionally obscures the lyrics in the rapid storytelling sections when the whole company are singing.

The show certainly benefits from the addition of Jamie Parker as the titular character, giving a performance of near-classical intensity and skill. Watching him age backwards from blustering, bewildered old gent to kind but haunted young man, with an economy and precision that takes the breath away, is a masterclass in stage acting. He is central to the action, yet slightly removed from it, inevitably for the progressively ever more dewy-skinned protagonist with a terrible life burden, longing to fit in but also petrified of discovery. It’s a magnificent achievement.

Opposite him as Elowen, the woman he loves and loses almost on repeat, Molly Osborne is an irresistible combination of quicksilver and steel, playful and pragmatic. Her ageing-up is done as impressively and subtly as Parker’s ageing down, and her singing pierces the soul.

In a uniformly brilliant ensemble cast, particularly effective are Benedict Salter as Benjamin’s understandably appalled father, pursuing him through the story like a conscience made flesh, and Philippa Hogg, marvellous in the original and equally good here as she gets to put over a multi-layered poisoned lullaby with equal parts sweetness and venom as the doomed mother. Jack Quarton does detailed, truthful work as a child Button champions who then ages into an adult who might be able to help him, and Ann Marcuson is gloriously vivid in a variety of roles.

Tickets for the first production became like gold dust, and I would imagine that’ll happen all over again as word spreads about a piece that could very well be the Next Big Thing. It feels grander, more monumental now, but still retains a sense of relatable, often heartbreaking humanity. It’s not a big leap to imagine this becoming a West End, then global, smash hit.

There’s still only a handful of musicals guaranteed to leave you in a soggy but uplifted heap, grasping for superlatives and thinking about when you can go back to see it again…but here’s one. It’s impossible to emphasise the impact and achievement of this utterly wonderful show without resorting to hyperbole, so I’m just urging you to see it. An unqualified triumph.