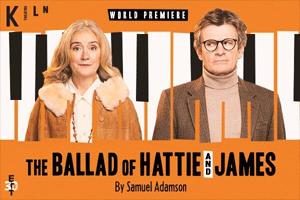

The Ballad of Hattie and James at the Kiln Theatre – review

The new play, starring Sophie Thompson and Charles Edwards, runs until 18 May

Samuel Adamson’s new play, were it a musical ballad, would challenge even the most competent conductor with its ambition.

There’s the epic scale, which spans a lifelong tumultuous friendship between its eponymous heroes (played by Sophie Thompson and Charles Edwards). Changes in tempo and focus as we yo-yo across decades between crucial moments in their relationship. Crescendos to time and multiple themes to explore – jealousy, addiction, misogyny, grief, the power of music and the cost of musical talent, to name a few. All while trying to depict two exceptional classical pianists with two actors who are, like most of us, not exceptional classical pianists.

Director Richard Twyman seizes the baton gamely and with invention. The pianist problem is solved by Berrak Dyer, who joins the cast on stage and plays exquisitely each time the script calls for ivory tickling from Thompson or Edwards. This leaves them free to express the emotion behind the music with movement or dance, a technique classical music aficionados should enjoy, along with many inside jokes about the art form. Jon Bausor’s simple set revolves us through time, and a screen gives us exact dates and locations, while the piano offers grounding continuity.

The polar-opposite natures of free-spirited feminist (and later alcoholic) Hattie, and awkward yet arrogant Benjamin Britten nerd, James, are played with skill and gusto. Thompson bowls about the stage with her trademark barmy charm, while Edwards keeps James somehow loveable, even while exploring decidedly unloveable traits. They are funny foils for each other, too. “James, how do you get through the day?” deadpans Hattie, when her friend (who has perfect pitch) rapturously tests out her mother’s piano, only to shut the lid on joy with a disappointed, “Oh God, it’s very out of tune.” Meanwhile, Suzette Llewellyn provides solid protean support, shifting effortlessly from school teachers and stepmums to lovers.

Well, call me James but something about this play, despite its promise (and many of the building blocks) of a mellifluous and moving ditty, feels similarly out of tune.

Perhaps most challenging is that Hattie and James’s connection never quite gets off the ground. There’s plenty of talk of the pair being the platonic loves of each other’s life (and an undercurrent of “will they, won’t they?”, confusing given that they are both openly gay). But their first encounter as teenagers in 1976 isn’t enough to convince us of their bond, and before long we’re whizzing into the future, watching painful partings and loaded reunions without enough investment to care as deeply as we yearn to.

And thanks to all of the decade-hopping, the events that buffet their friendship feel oddly timed. The reveal of the tragedy that first tears them apart comes too early to break hearts. And, perhaps to leave an intriguing breadcrumb trail through the maze of years, other bombshells are mentioned before they happen, leaving their fuses to fizzle amid conversation. By the time the bombs hit for real, their blasts feel muted.

This is a play that, without doubt, explores some fascinating ideas. James’s subconscious misogyny, and how tragedy can turn treasured art forms into beacons of pain were two subtle threads my mind tugged at on the way home. But to let so many ideas truly sing, the timing of this ballad might need some simplifying.