Review: The Fall (Royal Court)

Seven actors from the University of Cape Town dissect the consequences of the #RhodesMustFall movement in this new play

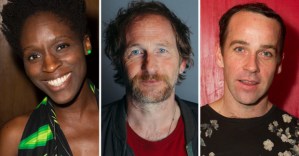

© Oscar O'Ryan

There was something resigned about the statue of Cecil Rhodes that stood on campus at the University of Cape Town. Sat in a chair, surveying the city, his chin resting on his right hand, he seemed to lean forwards apprehensively. It was almost as if he knew history was coming for him. As if he never got comfortable, even as his bronze body turned green. On 9th April 2015, after a swelling student protest, the British imperialist – a former prime minister of the Cape – was winched off his plinth and carted away.

In The Fall, at the Royal Court after an Edinburgh Fringe run, seven South African student actors recount the course of that #RhodesMustFall movement. Together, they describe protests that spanned organised occupations and literal shit-slinging, splintering into an enacted debate about the process of their protest – whether to educate and lobby or demonstrate and deface. Tensions brim into heated debate. Are they attacking a symbol instead of a structure? Is violence the right way to overthrow violence? It’s a vivid account. As Rhodes is ripped up, hovering over his plinth momentarily, "history is suspended in the air".

If the subject seems timely, it’s because the arguments have spread. Similar statues are coming down across America: confederate generals forced from their posts. History oughtn’t oppress us. If the arguments have become familiar, The Fall pushes on. What happens next? What replaces Cecil Rhodes?

That’s where the unified movement starts to fracture and split – women rail against men, light skin against dark, privileged against poor. It’s easy to pull something down, far harder to put something up in its place. Once you start breaking down power structures, where do you stop?

Told collectively and directly – old-school agit-prop – a lot of The Fall‘s drama comes from heated debate. Jostling argument does the job of action and, under Clare Stopford’s supervision, it covers the bases. The title’s a beaut. It cuts to the quick of the toppled statue while conveying the disintegration of the movement that brought it down – the inevitability of divisions prising people apart. That’s human, and it picks up the phrase’s theological connotations – The Fall being that first Fall of Man. In that, there’s the notion of Original Sin – and what’s colonialism (or Confederacy) if not that very thing? It’s a wrong we inherit in our different ways; a guilt society must absolve for if it’s to progress.

Music acts almost as a balm. The company’s accounts sit on top of South African song – struggle songs rooted in tradition that resisted apartheid and resurfaced against Rhodes. They instil The Fall’s power, underscoring speeches so that rhetoric seems rousing. They give the movement an urgency, and make the protestors a tribe. Some are percussive, beefed up with stamped feet; others almost purr – rich, warming voices that soak through your skin.

But the songs stand for something in their own right as well. They harmonize and overlap, many voices in sync – not just louder, but richer. Male voices underpin female voices. Individuals work together, the group gives way to soloists. It’s the sound of a movement, not the chant of a crowd. These songs aren’t merely singular. They’re plural and they’re present. Everything, in other words, that statues are not.

The Fall runs at the Royal Court until 14 October.