Neck of the Woods (HOME, Manchester International Festival)

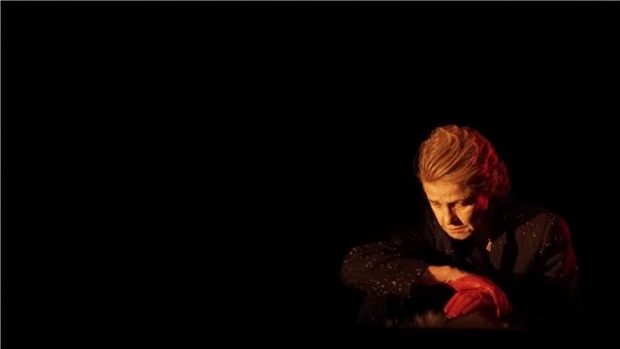

© Jutta Pohlmann

Manchester’s is a fusion festival. Alex Poots, outgoing director of Manchester International Festival, has a knack for matchmaking. In his decade at the helm, he has paired Punchdrunk with Adam Curtis, Elbow with La Halle Orchestra, Marina Abramhovic with Robert Wilson – all to great effect. Elsewhere this year, Wayne McGregor and Jamie xx, choreographer and DJ, have woven their work together for a much-lauded contemporary ballet, Tree of Codes, and, at the Whitworth, the Gerhard Richter/Avro Pärt exhibition is supposed to be excellent.

Matches don’t always strike, though, and so it is with Neck of the Woods – a collaboration between visual artist Douglas Gordon, pianist Hélène Grimaud, writer Veronica Gonzalez Peña and the actress Charlotte Rampling with the Sacred Sounds Women’s Choir for good measure. It’s not so much cross-arts as ships-that-pass-in-the-night arts.

It starts in the pitch dark with the sound of an axeman at work. We hear panting and the sharp thunk of an axe hitting wood, so loud you flinch every time. It sounds strangely animal, like a butcher hacking at flesh and bone, and it goes on for ages until, with a creak, then a lurch, then an almighty crash that makes the whole room shake, a tree topples to the floor.

Lights inch up on a glossy black stage: a strip of piano played by blood red hands; six axe handles clumped together like a bulrushes. Charlotte Rampling sits upright, dressed in beige and blood red, and purrs her way through a text – a nightmare about white wolves, then a purred recital of Red Riding Hood. She wrings her red hands and, behind a gauze, more hands seem to wave in the wind, as the choir voice the breathy sounds of the forest. Snow falls.

The combo resists concrete interpretation: I read it in terms of our relationship with the natural world, how we’re taught to fear it and to see ourselves as separate from it. Hands – and their prehensile thumbs – chop down trees, dance over keys and slice open wolves, but they are as much a part of nature as the woods and the wind.

Then the piece swerves: Red Riding Hood’s wolf starts to seem almost human, a predator of a different sort, and the huntsman, her saviour, a reflection of the storyteller, her father. Is Gordon suggesting that we project human ills onto the natural world? It’s never entirely clear and, Grimaud’s piano playing excepted, it’s never remotely interesting.

In fairness, Neck of the Woods doesn’t ask to be judged as theatre. The stage suits public pronouncements and political thinking. It addresses the world and confronts its audience. Gordon and co. want to have a little think about woods and wolves and stories and sex and human hands. It’s more a meditation; an art exhibition in the form of a performance and it approaches its subject from a number of angles. Trouble is it’s nowhere near taut enough for the stage. In the dark, our attention will drift – and drift it does.

Neck of the Woods runs at HOME, Manchester until 18th July. Click here for more information and to book tickets.