Matt Trueman's top ten shows of 2017

The WhatsOnStage critic picks his favourite pieces from the last 12 months

© Jonathan Keenan

10. The Welcoming Party, Manchester International Festival

Theatre-Rites is a very grown-up children’s theatre company, and Sue Buckmaster’s promenade piece for the Manchester International Festival taught adults and kids alike about the realities of refuge and asylum. Staged on the imported African timber of the 1830 Warehouse in Manchester's Museum of Science and Industry, it took a multicultural cast’s experiences and turned them into theatrical ones: immigration office games, interrogation cages and human conveyor belts. Best of all: a gorgeous cross-contintental journey in miniature.

© Johan Persson

9. Follies, National Theatre

It was Vicki Mortimer‘s set that got me – that crumbling, caved-in old Broadway theatre; bulldozed brick walls and rubble on red velvet. Silvery, sequinned showgirls shimmered like ghosts. As it dazzled, Dominic Cooke‘s staging went to work – a vast philosophical mediation on performance and past, aging and youth, nostalgia and regret. Woo-wee. Musicals can do that? My resolution for 2018: Brush up my Sondheim.

© Johan Persson

8. The Ferryman, Royal Court

Though not as indelible as Jerusalem, Jez Butterowrth‘s grand Irish family saga held me rapt. It was enchanting, rambling and still a tight-knit Troubles thriller, proving the salt'n'pepper beardyman a consummate stage storyteller. If three hours flew by in a maelstrom of geese, children and blarney, it stuck with me. Four months later I clicked why. Almost every Carney family member had disappeared somehow.

© Marc Brenner

7. Barber Shop Chronicles, National Theatre

Sometimes spirit does more than substance. Inua Ellams‘ roving piece about black masculinity, nipping into barber shops across Africa, had plenty of the latter, but it was the expansive, open-armed gusto of Bijan Sheibani’s staging that made it. Here was a cast clearly having a blast: a group of black actors – black men – showing their range and celebrating their diversity. Barber Shop Chronicles set a new bar: every character this rounded and rich. There's still time to catch it too – the show's running until 9 January.

© The Other Richard

6. An Octoroon, Orange Tree

Dizzyingly clever and bracingly upfront, Brandon Jacobs-Jenkins‘ remix of an old Dion Boucicault melodrama was a sublime example of thinking through theatre. Using black-, white- and red-face with as much nerve as verve, it exposes the outmoded, unexamined racism of Boucicault’s plantation tale, while restoring some of its original radicalism. Sounds heavy? Ned Bennett‘s spritely and surreal staging ensured otherwise, with Ken Nwosu unflappable as hero, villain and author in one. I can’t wait to see it again at the National next year.

© Robin Fisher

5. Re-Member Me, Almeida Theatre

If Robert Icke’s Hamlet took its time, Dickie Beau’s reclaimed history. Lip-syncing to a load of old Hamlets, Re-Member Me was an act of cultural exhumation – one that asked why we’re Hamlet-mad, but also who and what that eclipses. As it honed in on the late Ian Charleson’s forgotten Hamlet, it blossomed into a potent memorial to the victims of AIDS. The rest should not be silence.

© Alex Brenner

4. Palmyra, Summerhall

Clowning through clenched-teeth and chucking china plates at each other, Nasi Voutsas and Bertrand Lesca have turned the double act into a running duel. Their vicious two-man routine was an Edinburgh smash hit. The title changed everything, so that (un)friendly banter reflected the aggression across the Middle East. Tense as hell, Palmyra was a hostage situation and an arms race. Can destruction be creative? You bet.

© Sarah Lee

3. Consent, National Theatre

Nina Raine’s Consent – a modern classic, I’m sure – gained prescience as the year went on. Reflecting off two separate, contentious rape cases, it shed light on the issue of sexual consent, but Raine turned her title around and around like a Rubix cube. A play that looked at the privileged private lives of London lawyers, it asked how we consent to class, elitism and the law itself; who gets judged and who gets to judge. It’s a watchmaker’s play, made of many little moving parts and all too timely.

© Helen Murray

2. Suzy Storck, Gate Theatre

Suzy Storck shattered me. A portrait of insidious, invisible domestic abuse, it showed a young women pinned down by marriage, then ground down by motherhood. Magali Mougel’s play crept up on us – cutesy to start, wrung raw by the end. Caoilfhionn Dunne was devastating as Jean-Pierre Baro’s staging gradually inched up the violence. It changed the way I see the world – something I suspect might happen rather often at Ellen McDougall’s Gate.

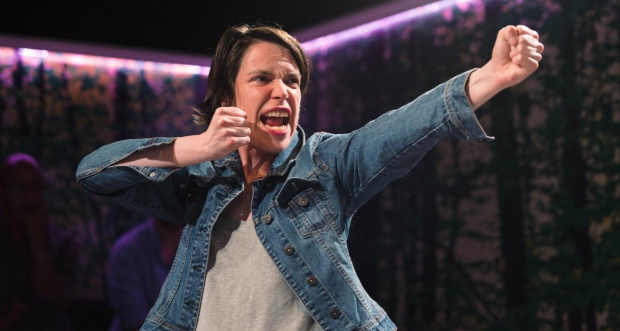

© Stephen Cummiskey

1. The Suppliant Women, Young Vic

If anyone still doubts the power of participation, The Suppliant Women surely settles the matter. As with The Events, another ATC show, a community chorus led David Greig’s strident adaptation of Aeschylus. Refugee women fleeing male violence, they were transfixing: achingly vulnerable, then ferociously united. A simple show that far transcended itself, it tapped into two contemporary crises at once – one personal, the other political. Staggering.