Lists like the New York Times' Best American Plays aren't stupid, they're helpful

As the American paper draws together 25 key plays since Angels in America, Matt Trueman asks what the value is of the ‘Best Of’ list

Lists are stupid, right? And while we're at it – since it's almost Tony time – awards are dumb too. It's an easy line to take. Art isn't a competition, after all. It's not there to be ranked, nor is there a standard to measure it by. There's no best or worst, no winners and losers. These are merely industry inventions. Art deals in ideas rather than ideals.

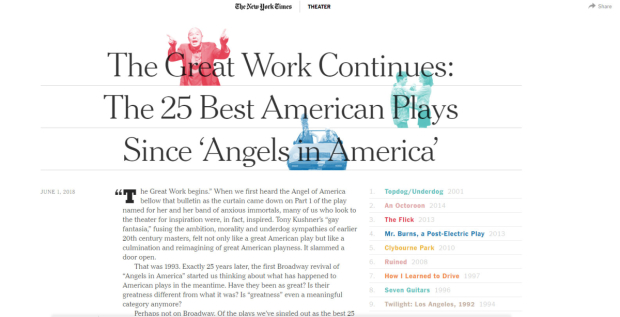

Last week, the New York Times published a podium-style piece, anointing the 25 best American plays of the last 25 years. Lists being lists, it would be easy to find fault. The boundaries are arbitrary – one play per playwright, only 'straight' plays allowed – and the caveats are clear. Mainstream work inevitably tends to win out, and scripted plays largely squeeze out slipperier sorts of show. It's easy to rail against what's in and what's out, because such lists are subjective, a product of who's picking and when.

Lists are a key mechanism for identifying the art that really stands up

Still, if the NYT list looks like clickbait (25 Plays To See Before Theatre Dies), a lot of care's gone into it. Five critics came together to argue the toss, and editors made space for scripts that didn't quite fit. There's a logic to it, too: Angels in America, arguably the last indisputable classic of the American stage, has just turned 25. Why not consider the scripts that have swum in its slipstream? The debate the list triggered is precisely its point.

Because lists like this aren't stupid, even if they're easily dismissed. They're a key mechanism for identifying the art that really stands up, helping to enshrine artworks as classics and sift the great from the good. Lists – and we're due a few ‘best of the decades' in 18 months time – are important.

Zooming out matters. At the risk of writing myself out of a job (some would say I do that daily), we critics aren't really best placed to pronounce on a play's real quality. We watch in the present, with all the hype and noise that entails. Over-excitement's a danger, as is missing the point. Shows can chime on the night and fall apart the next day, and a play that pings off a particular political moment can feel threadbare down the line.

Critics' standards are shaped by the immediate moment

We try to cut through that, to see a show for what it is, but our standards are shaped by the immediate moment. Lionel Bart wasn't as far off as we like to flatter ourselves when he distilled the reviewer's role down to judgement: "It's a good show, go see it; it's a dodgy show, don't". Where we go beyond that, to look at what a show's saying, we're still speaking about its place in the present. Classics transcend that.

The great Italian writer Italo Calvino tried to reach for a definition. "A work which relegates the noise of the present to a background hum", ran one. "Any book which comes to represent the whole universe", or "a book which has never exhausted all it has to say". He was writing about literature, but his words hold true for most other art-forms – certainly for plays. We still look into The Crucible and see ourselves and our world reflected, 55 years on. Ditto Doctor Faustus, the Oresteia and so on.

Yet, we've lost the habit of reviving new plays of late. We tend not to revisit our most recent successes – at least in this country. Time was a major new play would work its way round regional reps. Waiting for Godot had at least three run-outs within three years of its debut. Caryl Churchill's Top Girls was on in Bristol after a year. By contrast, Jez Butterworth's Jerusalem is due its first pro revival this month after close to ten years.

Our recent fixation on new writing and new work – the mantra that theatre must speak to and of the moment – has disrupted the way we shore up our great plays. That's shifting: Chichester has a Debbie Tucker Green double bill, and Sheffield Crucible's reviving Love and Information next month. It's still rare though and, in the absence of revivals that test a play's timelessness, lists looking back have to fill the gap.