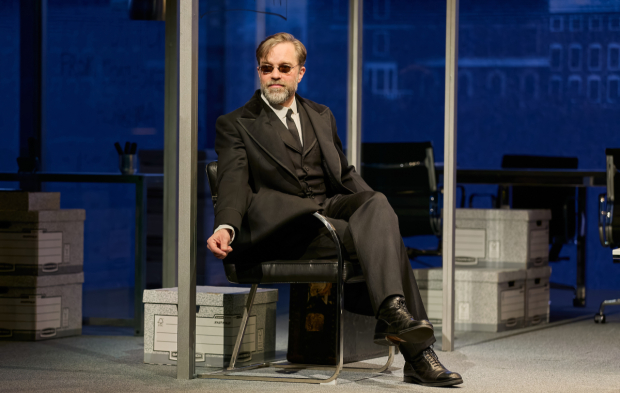

Hadley Fraser on painting with steam in ”The Lehman Trilogy”

© Helen Murray

From fronting major musical revivals to classic plays, the man has the enviable ability to appear anywhere. He even originated the prickly role of Sam in spooky thriller 2:22 A Ghost Story, which continues to run to this day in various starry productions across the West End.

His latest challenge is playing one of the leads in the ongoing revival of The Lehman Trilogy at the Gillian Lynne Theatre. The show is a three-strong-cast-led voyage through the century-spanning rise and fall of the Lehman Brothers – the famous banking institution whose collapse in 2008 will likely be remembered as a major moment in 21st century global history.

Having not seen the original production, Fraser is galvanised by the challenge Ben Power’s text, adapted from Stefano Massini, presents: “In terms of the dramatic and narrative structure I don’t think I’ve ever done anything like this. Multi-character shows [Fraser and co-stars Nigel Lindsay and Michael Balogun play all the characters from the founding of the Lehman’s company in the early 19th century through to the conclusion of the play] are a new and exciting territory for me.

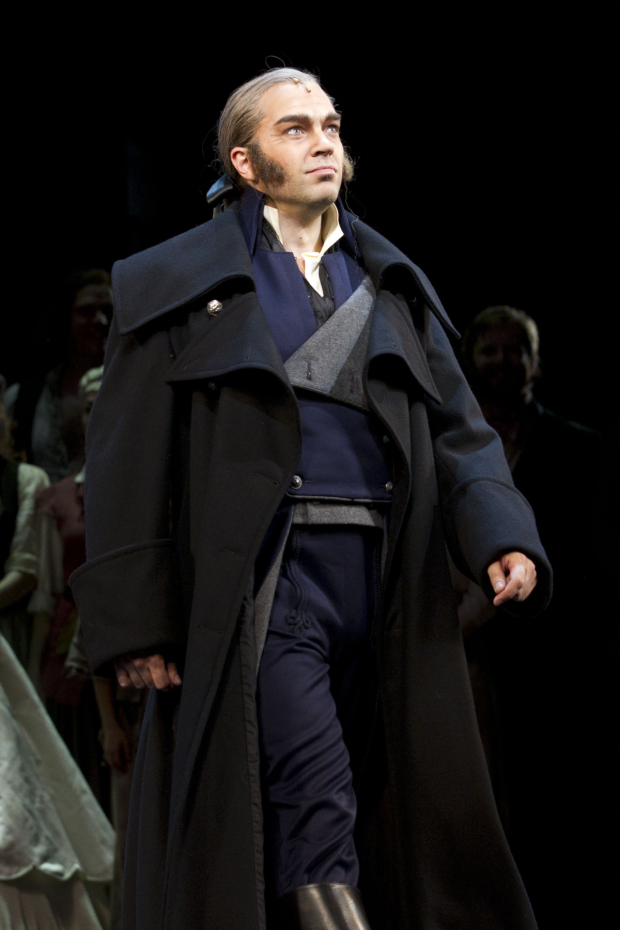

© Mark Douet

“There’s a difference to something like 39 Steps and Complicité where there might be the immediate immersion in character. In the rehearsal room our director Sam Mendes spoke about Picasso. One of the few painters who was successful in his lifetime, when the painter went to stay with people they’d drop great hints about him drawing something or painting something on a napkin so that they’d become millionaires overnight.

“One time, while staying with someone he didn’t particularly like, on his way out he told them he’d left them something upstairs – as soon as he left they rushed upstairs and he’d drawn something in the steam of his bathroom mirror.

“When we’re playing these multiple characters in Lehman, Sam said we’re painting in steam rather than with oils. It’s not a complete immersion in a fully formed thing, it’s more of a delicate suggestion. As a performer, that can be a challenge – for Nigel, Michael and I we have to pull it back slightly.”

I ask what it’s like, working on a show where audiences sort of know where it’s headed: “The ‘trilogy’ in The Lehman Trilogy is something that’s often ignored. Given the audience know how it’s going to finish, getting to the destination isn’t necessarily the most important thing. By the end of the play we instead have more fun when we start breaking the theatrical rules we begin with.”

© Mark Douet

As Fraser notes, Lehman is an important asset to the West End: “There will always be room for epic plays – shows without bells and whistles. Es Devlin’s design is, of course, out of this world, as is the projection, but it ultimately relies on the three of us to tell the story. It feels quite like some sort of primal exercise – we could be gathered round a campfire in medieval times as a group of travelling players – that feels very conscious and not something that is shied away from.”

We pivot to talk Fraser’s career more widely, especially the way in which he bounces quite seamlessly from the musical sphere (with roles in Young Frankenstein, Les Mis, Phantom, The Pajama Game and more) to the play sphere (Saint Joan, The Deep Blue Sea, The Vote and Coriolanus) and back again: “I’d be hesitant to suggest there’s a grand plan – it’s much more by accident than by design. Certainly I’ve been able to make the choice occasionally – and I count myself lucky I’ve been able to do that.

“Early in my career I did consciously make a few decisions to guarantee I was always seen being able to do both – doing something like Chess followed by Lehman – when I started out I’d have just not believed that was possible.

“Things that have been most surprising or exciting for my career have, luckily, also been surprising or exciting for me. Like when Lehman appeared I didn’t know it was coming or even expect to be asked to audition for it. But even brand new shows – there’s a lot to be had in making new shows, new writing. Going forwards, doing a decent spread of new writing as well as old – both across plays and musicals – will make me a happy chap.”

Fraser has nothing but praise for some of his recent projects – including the UK premiere of Annie Baker’s hit The Antipodes, which ran at the National Theatre. Baker is, to Fraser, “the most brilliant playwright encased in the most beautiful, quiet human. She’s a singular writer. Plays that investigate storytelling can sometimes spend too long instead investigating their own naval, but The Antipodes succeeds where others fail.”

© Dan Wooller

Another recent project was the ill-fated City of Angels – which closed before opening night due to the onset of Covid lockdowns. Fraser hopes that one day it’ll be back: “There will always be a desire on behalf of Josie Rourke [director] and Nica Burns [producer] to bring it back – though it’s an expensive show at a precarious time – a big production that had a sh*t-hot cast (who knows if we’d be able to get them all returning). Nevertheless, if I’m 83 and someone is asking me to play Stine, I still would.”

What comes through talking to Fraser is his respect for punters and spectators – those who continue to watch him in action: “I’m very keen to give audiences the benefit of the doubt in terms of their appreciation. There’s a huge knowledge without the theatregoing community and they do not suffer foolish shows gladly – unless [he laughs] what they’re going for specifically is a foolish show.”

It’s an attitude that sits at the heart of The Lehman Trilogy – a three-man odyssey that Fraser describes as “physically exerting” in the similar vein to a blockbuster musical (“You come off sweating knowing you’ve probably lost several pounds”).

As both forms come so naturally, it’s no surprise he’s kicking it out of the park at the Gillian Lynne every night.