Boys from the Blackstuff at the National Theatre – review

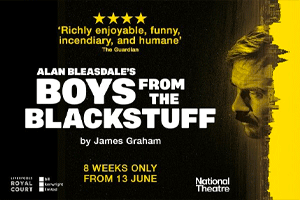

James Graham’s play, based on the classic TV series, continues at the National’s Olivier Theatre until 8 June before transferring to the West End’s Garrick Theatre from 13 June

It’s impossible to overestimate just how significant Alan Bleasdale’s television series Boys from the Blackstuff was if you were around in 1982. Here, in five superlative, succinct, funny and heartbreaking episodes was a reflection of the brutal effects of unemployment on Britain in the early years of Mrs Thatcher’s government.

Thatcher’s unmistakable tones open James Graham’s stage play drawn from the series, reminding everyone of the human dignity and self-respect lost by unemployment. Then, in sharp ironic contrast, under the rusted iron structures that form the centrepiece of Amy Jane Cook’s flexible set, we see the truth beyond the honeyed words: five men standing in line at the benefits office, answering questions about their availability for work.

The play, originally produced at Liverpool’s Royal Court, and soon to transfer to the Garrick Theatre, doesn’t have the same visceral impact as the series. Its compression means that it becomes episodic, so that the lives of these men (and it is mainly about men) become emblematic rather than richly involving and felt as they were in a more discursive medium.

Nevertheless, it is a thoughtful and moving piece of writing. Its humane view of the value of work and of people remains a sharp and passionate reminder of how a society is impoverished both physically and spiritually if those struggling with poverty and under-employment are regarded not as individuals but as scroungers. It’s a cry from the heart that rises beyond history to become a lesson for today.

The play builds its structure around the contrasting figures of the desperate Yosser Hughes, stalking the action wild-eyed, crying “gizza job” and the gentler figure of Chrissie, too kind and conciliatory for his own good. Both Barry Sloane as Yosser and Nathan McMullen as Chrissie are walking in the footsteps of legendary performances from Bernard Hughes and Michael Angelis, yet they lend their own energy and commitment to bringing their conflicting attitudes to their disintegrating lives into sharp focus.

Kate Wasserberg directs with a smart sense of the liveliness embedded in Bleasdale’s writing that Graham has preserved. From scene to scene, humour and tragedy are closely interlinked. Many scenes land with great power: Snowy’s great hymn of praise to the majesty and satisfaction of plastering, just before the “sniffers” from the Department of Employment track him down with fatal consequences, or Yosser’s encounters with the clergy at both ends of Hope Street, when he – famously – confesses “I’m Desperate, Dan”.

The story of Liverpool, too, makes its mark, constantly reflected in Jamie Jenkin’s wonderful videos of the Mersey, and in the memories of ex-docker George (Philip Whitchurch, gently impressive). He beautifully describes the way the riches of the world made their way into the city via its docks – until Liverpool’s significance as a port was lost when the Mersey proved too shallow and too thin for containers, and the growing trade with Europe meant it was literally facing the wrong way.

The world conjured is as lost now as that of the Victorian cotton magnates. Those docks in modern Liverpool are a tourist attraction and zero-hours contracts have replaced the absence of jobs. Yet when Lauren O’Neil’s Angie, a woman at the end of her tether, talks about being hungry and being unable to feed her children, the relevance of this play is as clear as ever. Its truthfulness rings like a bell – and its reappearance has prompted the BBC to show the original series once more. A modern classic has been resurrected.