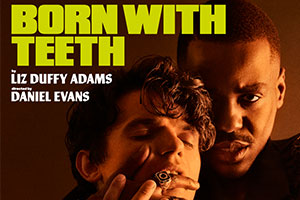

Born With Teeth review – Ncuti Gatwa and Edward Bluemel are playwrights dancing with death

Liz Duffy Adams’ world premiere play runs at Wyndham’s Theatre until 1 November

Put Shakespeare and Marlowe in a room and see what happens. That’s the basic idea behind this whirling counter-history, that spins the known facts of the relationship between the two men into a fantasy of flirtation, spying, love and suspicion.

It’s an odd confection, at once challenging and comic, slightly circuitous and oddly revealing. Written by Liz Duffy Adams, and already seen in the US in a different guise, it’s brought to vital, charismatic life by its casting: Edward Bluemel (of Killing Eve and My Lady Jane fame) as gentle Will and Ncuti Gatwa, so recently the Doctor in Doctor Who, as dangerous Kit.

But the play, directed with great bravura by Daniel Evans, doesn’t open with their writing, but with an image of them shouting in torment – tortured by the secret state that Elizabeth I brought into being to hold on to her perilous power amidst the religious wars of the period. “That didn’t happen,” says Shakespeare, stepping forward, and setting the scene. “But poets have big mouths.”

The atmosphere of nervousness continues as the front screen rises, and the actors are plunged into Joanna Scotcher’s set defined by Neil Austin’s banks of dazzling spotlights. In a private room at an inn, Marlowe and Shakespeare are meeting to collaborate on – though you are never actually explicitly told this – Henry VI parts two and three, a partnership that is actually backed up by a lot of current academic thinking.

The battle lines between them are quickly drawn. Marlowe, gorgeous in tight leathers (Scotcher’s clever costumes are remarkably descriptive) is gay, dangerous and constantly needling Shakespeare about how if he wants to get anywhere, he can’t rely on hard work alone. He will need to know people, and – the implication is – to betray people for money. Shakespeare is gently resistant to the notion, in awe of Marlowe’s genius, in thrall to his appeal, but quietly insistent that he just wants to get on with the job and write.

The dialogue is snappy, and often very funny. “We’re the same age,” Shakespeare moans when he’s being patronised. “Not in stage years,” retorts Marlowe. There’s a lot of retrospective irony in Marlowe’s constant bragging that he, the university educated son of a shoemaker, is “one of the greatest poets of our age” while Shakespeare, the country boy who went to grammar school and is versed only in Latin, Greek and rhetoric “will never be anything but a minor talent.” There is a fair amount of snogging.

But there’s also a lot of under-explained allusion to historical figures and their circles; background colour that makes sense if you know, but not a lot if you don’t. Not all the tension of Evans’ direction and the energetic choreography of Ira Mandela Siobhan can quite disguise the fact that the play returns again and again to Shakespeare’s reluctance to play the spying game and Marlowe’s threats to betray him. It doesn’t progress its themes so much as circle around them.

The most interesting sections – at least if you care about Shakespeare – are those which probe the differences between the two writers. Marlowe insists on inserting his own bold personality and controversial beliefs into every line he wrote while Shakespeare’s instinct is to disappear, to lose himself in every character. The moment when the two men act out Shakepeare’s inserted scene in Henry VI showing the love between a husband and wife is remarkably tender. The play’s concluding note, that Shakespeare consistently wrote Marlowe (who died in a tavern brawl in 1593 at the age of 29) back to life is intriguing.

But it is the acting that holds you. Gatwa is electricfying as Marlowe, all flashing wit and sexy swagger that he always manages to suggest is hiding not only a passion for a double life but a terror that it might all vanish. As Shakespeare, Bluemel is surprisingly endearing, suppressing smiles like a schoolboy, all nerves and anxiety on the outside, but with a calm, enduring centre. It’s a performance full of grace and charm.

The two men hold the play gently in their hands – “Is that an egg metaphor?” Marlowe asks, quick as the knife he carries, when Shakespeare tries out a line. Their efforts blow away a certain dryness, a whiff of literary connoisseurship, and fill the evening with rich life.