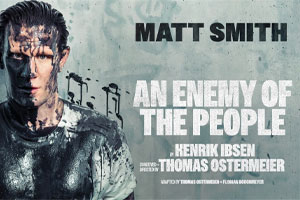

An Enemy of the People West End review – Matt Smith wades into the murky waters of modern politics

The radical take on Ibsen comes to the West End

On the night I saw the legendary German director Thomas Ostermeier’s English-language version of Henrik Ibsen’s An Enemy of the People, the death of the Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny had just been announced, and people laying flowers on the streets of Moscow were being systemically arrested.

Rarely can this 1882 howl of anger about one man’s inability to stand out against corruption have felt so pertinent, all the more so because Ostermeier’s production (first seen in 2012) tilts the balance so that instead of being a psychological drama about rectitude it becomes an impassioned examination of society and the powerlessness of democracy to check an abuse of power.

With Matt Smith in the starring role as Dr Stockmann, the scientist who discovers that the water at a local spa is polluted, it’s a searing cry from the heart about the erosion of civil and moral value, but also a depressing examination of the way that money rules in the modern. Opposed to Stockmann’s truth-telling are all the vested interests who rely for their wealth on the success of the spa.

But this is also very much a version of the play for the post democratic age. In Ostermeier and Florian Borchmeyer’s adaptation, with an English language version by Duncan Macmillan, Stockmann’s cry against liberals becomes “the greatest enemy of truth – is the f**king liberal majority. That’s who robs me of my freedom. That’s who has eroded our faith in experts, in evidence, in truth.”

Thus the great central act of the play where Stockmann extends his frustration with the small-minded town politicians (led by the mayor, his brother) are seeking to suppress his discoveries in the interests of the town’s prosperity into a sweeping attack on a rotten culture, becomes an open meeting where the house lights are up and the audience are invited to share their views on the billionaires who fund moon-shots when people are starving, and a narcissistic society of stuff that stops functioning opposition to greed.

It’s both patronising and electrifying, an impassioned speech which at once shares the difficulties the world is facing – with specific UK references to food banks, and the Post Office – and yet also underlines the sense of powerlessness most people feel. In taking Ibsen’s sub-text and turning it into the main text, Ostermeier is using theatre as a political rallying place, somewhere to ask what we really think.

Yet, with great precision, he frames the action to reveal the difficulties of that. In this version, Stockmann and his mates are exactly the kind of “wokey-cokey liberals” that Nigel Lindsay’s brusque industrialist Kiil, stalking the place with his Alsatian in tow, accuses them of being. In the opening scenes, Stockman, his wife (Kiil’s daughter) Katharina (Jessica Brown Findlay) and their friend Billing (a wonderfully laid-back Zachary Hart) are more interested in band practice and singing David Bowie’s “Changes” than they are in real action to change the world.

Bogged down by a new baby, hard up and finding it hard to grow up, they espouse all the great, good causes, but show little understanding of what they can do. The weak-spined newspaper editor Hovstad (Shubham Saraf) is just as bad. Everyone’s talking the talk. It’s no wonder things turn vicious.

All of this is presented with the verve and energy of a rather wild sitcom, on a witty set by Jan Papplebaum where the walls are eventually literally whitewashed. In the midst of events, Smith brilliantly holds the centre, his edgy intensity suggesting real jeopardy as Stockmann gradually becomes conscious of the effect of his actions and weighs what to do next.

He’s a superb actor who listens as intently as he moves, giving weight and ballast to a production that might fly too far off its axis. His scenes with the mayor, his brother, who Paul Hilton gives a twitchy, slippery dynamism, are compelling; both men manage to suggest the tense family dynamics beneath the high stakes for society itself.

The whole thing has a contemporaneity that makes it feel urgent, a tribute both to Ibsen’s prescience and to Ostermeier’s rigorous analysis of its relevance. If the ending is depressing, that is because it sums up so precisely the state of things.