George Takei’s ”Allegiance” at the Charing Cross Theatre – review

© Danny Kaan

Allegiance only managed 111 performances during its 2015-16 run on the Great White Way, but thanks to a well-received pro shot screen version, a subsequent West Coast staging and the sheer indefatigability of Mr Takei, this is a musical that refuses to go quietly. In fact, in Tara Overfield Wilkinson’s UK premiere production at the Charing Cross Theatre, it refuses to do almost ANYTHING quietly… and the result is a rousing, haunting, surprisingly multi-textured piece of musical theatre that maintains, for the most part, a healthy balance between cynicism and sentimentality, and sheds light on horrendous real-life events that were only taught about and acknowledged comparatively recently.

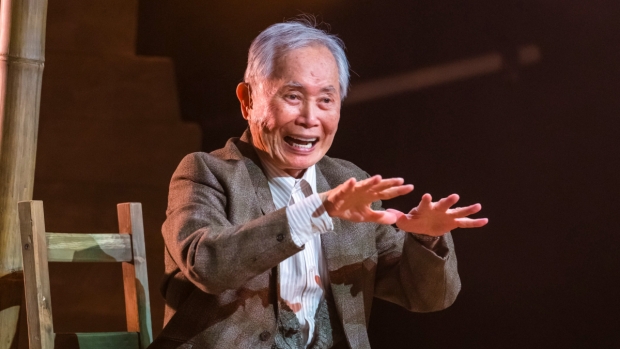

Now it’s London’s turn to bear witness to this tale of the forced internment of over 125,000 Japanese-Americans by the Roosevelt administration during World War II. Takei spent some of his childhood in one of these camps and his presence lends an authenticity and gravitas to a musical that is by no means perfect but has sufficient emotional heft and dramatic meat to make a pretty satisfying evening in the theatre. Marc Acito, Jay Kuo and Lorenzo Thione’s book is part history lesson, part family saga and part love story, shot through with unexpected moments of touching comedy, and finds dramatic tension in the contrast between the Japanese-Americans who were determined to prove their patriotism to Uncle Sam, and those who revolted due to their treatment. It’s occasionally a little confusing but it never trivialises the trauma of war and imprisonment, and neither does it make it such a slog that it’s hard to sit through.

Overfield Wilkinson’s staging is sublime, confidently managing a playing area where the audience is arranged on both sides but where focus and sightlines are always clear. Some of the stage pictures are unforgettable – a train carrying people across America to the internment camps assembles in seconds using just packing cases and human bodies, a garden tree is disassembled to make confining walls – and the way the actors move in the space often verges on the hypnotic, blurring the lines between direction and choreography. In the moments where the dancing explodes, Overfield Wilkinson’s work is again terrific, and crucially it always looks like real people moving, not just a well-drilled team of chorines.

© Tristram Kenton

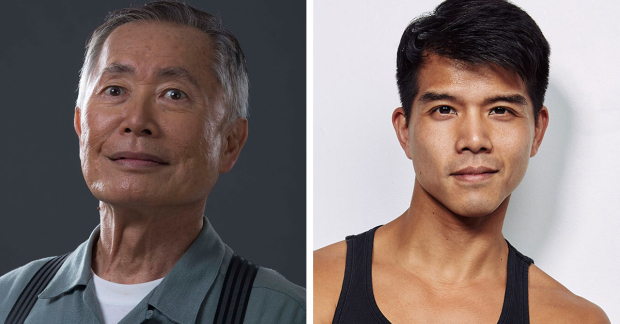

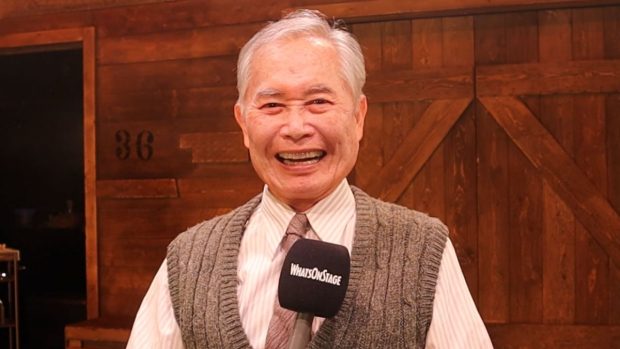

Takei is a lovely stage presence as grandfather Ojii-chan, then turns up the intensity as Sam, the embittered grandson looking back at his family’s tragic past. It’s a genuine thrill to encounter him on stage, as it is to see the West End debut of Broadway leading man Telly Leung as the younger iteration of Sam. Leung brings charm, pathos and a glorious ringing tenor to the part and there’s beautiful work from Aynrand Ferrer and Masashi Fujimoto as his sister and father respectively, both rather more complex figures than they first appear. Ferrer’s voice is an astonishing instrument, serene, sweet and powerful, and uncannily reminiscent of Lea Salonga, who originated this role on Broadway. The challenging ballad “Higher” that climaxes the first half is a real corker, and Ferrer’s rendition of it is stupendous. Megan Gardiner is delightful as the steely but kind nurse that Sam (quite understandably) falls in love with.

Given the misguided atrocities directed at Japanese-Americans following the 1941 Pearl Harbor bombing, some of which are dealt with pretty unflinchingly here, it is perhaps surprising that the overall tone of Allegiance is less furious than it could be. The show is seldom either bland or hysterical, with a sweetness and lightness of touch alongside the high drama that one would not necessarily have expected. If ultimately it succumbs to the tear-soaked Les Mis finale trope of dead loved ones warbling soulfully from beyond the grave, the emotion feels genuinely earned, and you’d have to be made of stone not to shed a tear at the conclusion’s revelation and reconciliation.