”Dixon and Daughters” at the National Theatre – review

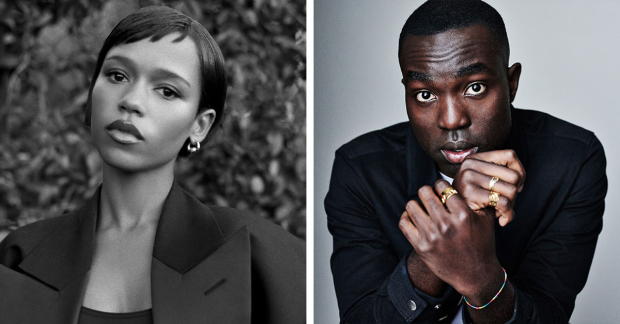

© Helen Murray

Its essential aim is to examine the question most often asked of survivors of domestic violence and abuse – why do they stay? It does this by showing a family torn apart by the decision of a victim to take an abusive man to court.

It’s hard to write about without giving too much away, because some of its impact depends on the sense of dread that Bruce brings to the play, letting its secrets emerge slowly. But it begins when Brid Brennan’s tightly-wrought Mary returns from a short spell in prison to be greeted by her daughters Julie (Andrea Lowe) and Bernie (Liz White) and her granddaughter Ella (Yazmin Kayani).

The anger and resentment in the air of Róisin McBrinn’s carefully naturalistic production are heavy; so is the memory of their dead father which lies over the daughters “like a lead blanket”. Kat Heath provides a set that shows the rooms of their childhood home, both upstairs and down, some semi-screened from view, which has both a dramatic and a metaphorical purpose. Paule Constable’s lighting is equally dual-purpose and equivocal.

© Helen Murray

As secrets are revealed, the family dynamics emerge too. Julie, played with sulky unhappiness by Lowe, is on the run from a violent boyfriend, struggling to give up drink and constantly picked on as useless by her angry, prickly mother. White makes Bernie the quietly efficient coper, earnestly trying to smooth over the cracks, while Brennan reveals the fear beneath Mary’s aggressively hard-done-by exterior. Kayani, in a wonderfully fresh and open performance, is like her mother in trying to be the good girl; but her own life has been fractured by her unhappiness at university.

The action is enlivened, and the story complicated by the intervention of Alison Fitzjohn’s forceful Briana, constantly intoning self-help mantras in her determination to make her life meaningful, and Posy Sterling’s loose-canon Leigh, whom Mary has met in prison and is determined to mother in a way she has not managed for her daughters.

There is a lot going on and arguably too many stories of misery at the hands of men. The action sometimes loses momentum as another thread emerges. Nevertheless, the honesty of both writing and performances shines through, making the play an involving examination of exactly why women continue to suffer in silence, in homes where they should feel safe.