Boris Godunov (Royal Opera House)

© Catherine Ashmore

It comes at a cost, since the absence of tacked-on heroine Marina means one of the opera's most celebrated scenas is missing, but the gains in dramatic tautness are unmistakable. Set in a recognisable suburb of Jonesland complete with repetitive wall patterns, duplicated portraits and endless lateral processions, this Boris is a close-focused drama of ambition, usurpation and assassination.

Boris Godunov is crowned Tsar following the mysterious death of the true boy-heir, Dmitry. Did he do it? That question clouds his reign and allows a false pretender, Grigory, to hatch a plot in which he will 'become' Dmitry, claim he was never killed, and foment an overthrow.

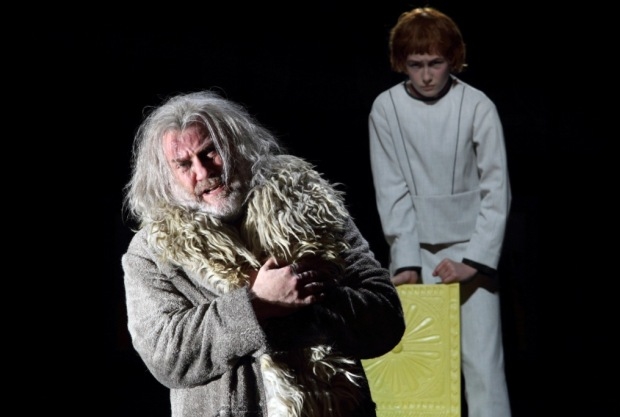

At the heart of this production are four shatteringly rich and expressive performances: David Butt Phillip as Grigory, intense and powerful in his idiomatic singing even though his character disappears halfway through the opera and is only referred to in the third person thereafter (I'm skirting round a spoiler here), Ain Anger as his mentor, the monk Pimen, John Graham-Hall as the duplicitous Prince Shiusky – and Bryn Terfel.

'A lethal eye'

It's not often the Welsh wizard passes as a light singer, but compared to some of his profondo predecessors he is mellifluous. That characterful bass-baritone lies just high enough for musicality to trump darkness. His Boris exists in a state of mental agitation as he's haunted by the murder of little Dmitry, an act we see played out again and again in a gallery above the stage. Terfel's casting, which some had questioned, is entirely consonant with Jones's interpretation.

There's a link to the past in the appearance of John Tomlinson, a great former Boris, of course, in the character role of Varlaam, which he carries off with aplomb, and a nod to the future in the outstandingly mature performance of young Ben Knight as Boris's son Fyodor. A role that's often taken by a woman packs an especial punch here thanks to the teenager's touching vocal and dramatic strengths.

Set designer Miriam Buether and costume designer Nicky Gillibrand keep well away from Tsarist tropes in a timeless, placeless environment that allows Mimi Jordan Sherin's lighting to draw the eye always where it needs to be. In a staging with no extraneous imagery, therefore, the attention and tension are unbroken, and only a questionable bulk order from Wigs 'R' Us proves in any way distracting.

Antonio Pappano conducts with a lethal eye for dramatic brilliance. The constant flow of his orchestral colouring make a nonsense of the oft-heard claim that the 1869 version of Boris Godunov lacks melodic interest, and when he unleashes Mussorgsky's bells the house resounds to their savagery. As for the Royal Opera Chorus, the men in particular remind us that their ENO colleagues may be hitting the headlines but they're far from being the only show in town.

Boris Godunov runs in repertory at the Royal Opera House until 5 April. The performance on 21 March will be broadcast live to cinemas.