Review: The Antipodes (National Theatre)

© Manuel Harlan

You've got to hand it to Annie Baker. The woman can write. Her plays may not be to everyone's taste, but word for word, line for line, they have an audacious authority, a sense of being absolutely the strange and magnificent thing she intends them to be. They are unlike any other plays being written today.

The National Theatre has so far imported three of her works. In The Flick (2013), three people potter around an empty cinema for more than three hours; in John (2015) a couple visit a peculiar B&B and talk to the owner and her blind friend for more than three hours. The Antipodes, from 2017, only lasts two unbroken hours, but in many ways, it is even more challenging and elusive: a play about plot that has none of its own, an examination of fiction and reality that refuses to give up its own mysteries.

It is set in a sleek, modern conference room, with patterned carpet, chairs on castors, a huge glass conference table and mountainous pile of mineral water boxes (designed by Chloe Lamford, who also co-directs). Overhead, there is an elaborate circular light fitting – a conscious visual representation (because everything in Annie Baker's world is meant) of the discussions that will ensue about the way it is possible that time moves in a spiral, so that a man could travel the world to the antipodes – the place on the opposite side of the earth – and return to find himself facing his own retreating form.

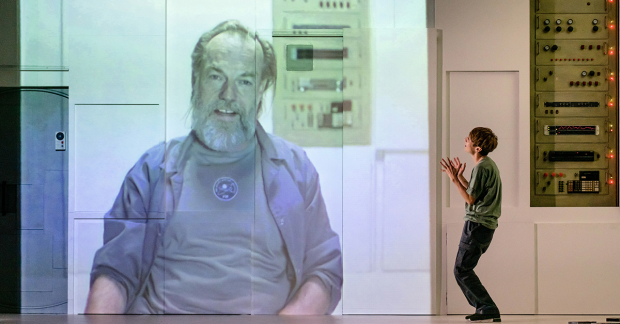

Such ideas are prompted by requests from Sandy (Conleth Hill), the solipsistic and preening maestro who sits at the head of the table asking his team (six men and one woman) to tell him stories as part of a brainstorming session of some sort in this "sacred space". "The rest of the world might be going to hell, but stories are better than ever. And we've been given the opportunity to create something unprecedented….We can change the world."

Story telling is thus the explicit theme and the actual fabric of the play. Faced with a request for total honesty, the characters share their experiences of losing their virginity, of their fears and regrets. One character, Danny M2 (marvellously shy Stuart McQuarrie) tells a strange story about his attitude to caring for a chicken; but he baulks at revealing too much. "Sometimes when I tell personal stories, it doesn't feel real." Another, Dave, (nervy Arthur Darvill) permanently anxious to please his boss, recites tales of trauma but glosses them as comedy. Sarah, the ever-helpful PA (wonderful Imogen Doel) whose changing wardrobe marks the passage of the days, pops in to make a Grimm family saga into a personal anecdote.

Other stories remain hidden: what are the complications of Sandy's life that draw him from the room? Have the woman Eleanor (perky Sinead Matthews) and the black man Adam (Fisayo Akinade, terrific) been employed to improve diversity? Why is Josh (nervy Hadley Fraser) the only one without an identity badge? Outside the room, the world seems to be going to pot. Storms are raging. The stories dry up, until Brian (the perpetual notetaker, Bill Milner) is driven to desperate measures to conjure new myths.

Themes appear: monsters, what they are and how they emerge; who has the right to speak in any room; the workings of time; the lifespan of animals threatened by man. Heaven and hell are regularly mentioned; the characters seem to be stuck in limbo, trying to free themselves by their own invention. Nothing is stated, but in the end the power of story to help humans understand themselves is suddenly vindicated.

Baker's own production is reticent and so deliberately quiet that it flattens the sharp shifts of mood from satire, to reflection, to horror and high comedy (including a brilliant scene where communications break down as the assembled company try to communicate with a disembodied voice.) But she cleverly captures the sense that this is all not quite real; the slo-mo shifts of action, the frozen poses create the mood of a dream.

It's all so sharp, and so pertinent, venturing to worlds where most playwrights fear to tread. Hours after the performance had ended, I found I was still thinking of the play and its themes, pulling at threads, thrilled by its rich ambition. Annie Baker. What a writer.