Review: A Number (Bridge Theatre)

© Johan Persson

One of the thought-provoking qualities of the current revivals of the work of the great Caryl Churchill currently taking place across London, is that they are directed by women – perhaps casting them in a subtly different light, certainly opening them to new conversations in a new decade.

Following on the heels of Lyndsey Turner's look at Far Away at the Donmar, comes Polly Findlay's take on A Number, a troubling hour-long inquisition about the nature of family and the possibilities of modern science. Its premise is devastatingly simple: a father, Salter, is confronted by his son who has just discovered he is not unique. He is cloned from another, slightly less satisfactory version, at his father's request. An irresponsible doctor has created many more duplicates. Perhaps they should sue, suggests the father.

A Number's original incarnation – at the Royal Court in 2002, starring Daniel Craig and Michael Gambon and directed by Stephen Daldry – emphasised the scientific dystopia; it had a clinical coolness about it that thrust the spotlight onto its ethical issues. Here Findlay and her designer Lizzie Clachlan (who also designed Far Away) let its themes arise in the most homely of settings – a scruffy, battered suburban front room. This gently underlines one of Churchill's most unsettling qualities, the way she allows the epic to emerge through the domestic – a conversation in a garden, a scream in the night, a gesture across a kitchen table.

I am not in fact utterly convinced by the way that the set revolves between scenes, revealing the home from different angles, allowing a fireplace mirror to suggest an infinite recess of possibilities of fathers and sons. It seems to me to overcomplicate an already elaborate structure. Nor do I like Marc Tritschler's interscene music, which seems overemphatic.

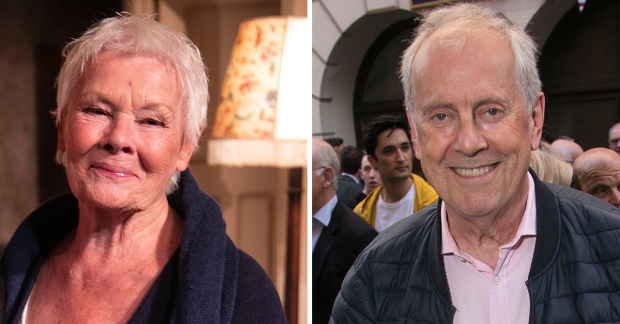

However, the production's approach liberates the extraordinary, perturbing emotion of the play. By placing Roger Allam's crumpled, battered father in this setting, his terrible, fallible ordinariness is revealed. Allam plays him brilliantly, as a slightly wheedling, bemused narcissist, whose belated realisation of the consequences of his actions dawns only slowly. "I wanted the same but different", he explains, trying to justify why he replaced angry, difficult Bernard 1 with gentle, loving Bernard 2.

As three versions of the same genetic code, Colin Morgan is utterly riveting, distinguishing beautifully between each incarnation. Bernard 2 is all wounded confusion – "any number is a shock" – his sense of uniqueness undermined by the revelation of his multiplicity, his grasp on his relationship with his father disturbed. He folds his body into himself, touching his face as if trying to validate his existence, while Bernard 1 – the child we come to think Salter has neglected – is all truculent swagger and anger.

Yet the moment when he sits on the sofa, absolutely still and silent – as Salter reaches towards him– is utterly riveting; you see all the hurt and vulnerability of this little boy, alone in the dark, rising through Morgan's face and body. The contrast with the breezy happiness of the final clone we encounter, trying to offer his own form of comfort, emphasises the tangled web of nature, nurture and love that Churchill has so skilfully woven.

On the table next to Michael, the final visitor to the Salter home, whose genetic heritage – "we have 30 per cent of the same genes as a lettuce. I love that" – means far less to him than his love for his wife, sits a photograph of a smiling boy, origin of all the genetic material and all the anguish. It's a characteristically subtle touch in a fine and superbly acted rethinking of a provocative and powerful play.