1984 (Almeida)

Towards the end of this brilliantly imaginative adaptation of George Orwell’s great dystopian novel – an Almeida co-production with Headlong and the Nottingham Playhouse – someone says, “People won’t look long enough from their screens to see what’s really happening.” Is that Orwell? If so, it’s another sign of inexhaustible prophecy; if not, it sounds dead right.

The anthropomorphic theatricality of Animal Farm has always guaranteed its life on the stage. 1984 in 3-D is much harder, but its talk of Newspeak, thought-crimes and Big Brother fuses directly into Kafka, Harold Pinter and Martin McDonagh’s The Pillowman: it’s the ultimate grim parable of the repression of individuality, the triumph of state over citizen, regulation over love, censorship over free speech.

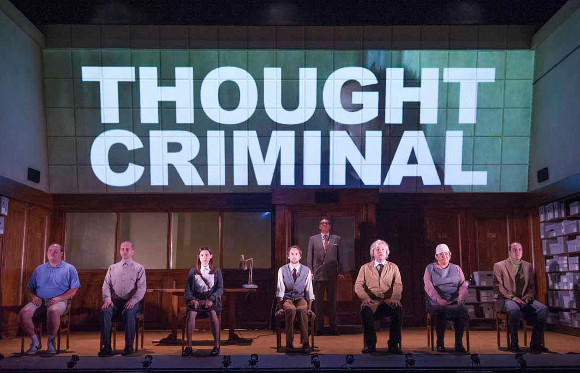

This adaptation and production by Robert Icke and Duncan Macmillan shows Winston Smith – beautifully characterised as a febrile, open-eyed innocent by Mark Arends – writing his diary which is being picked over in a sort of retrospective book club in the all-purpose ministerial setting of Chloe Lamford‘s stunning design; in contrast, the rebellious hideaway he shares with Hara Yannas‘ lovely Julia is projected on film on the top half of the set, as though it were a cinematic interlude.

Within this framework, we have scenes of routine and repetition, threaded with a hint of the banished past in a small girl’s singing of a forgotten street song, “Oranges and Lemons,” the grisly brush with the Brotherhood (also on film) and the final showdown in Room 101, where Winston meets Tim Dutton‘s all too plausibly intoned and grey-suited O’Brien. The nightmare interrogation in the Ministry of Love leads to torture by fingertips, then teeth, electric shock treatment and the tunnel of rats.

“The price of sanity is submission,” says O’Brien, and the price of survival is betrayal. For this is a love story. In the book, Winston and Julia find each other in ecstasy in the countryside; here, they go mad in the office, ripping at the walls and displacing an avalanche of paperwork. The power of the Orwellian metaphor is enhanced by the particular detail at its centre.

Michael Radford’s 1984 movie starring John Hurt as Winston and Richard Burton as O’Brien was pretty good, but this version reinvents the world of totalitarianism in the Soviet-style state of Oceania with a much more appropriate and theatrical formality. There is a trip wire of normality in the staging until, in Room 101, the cast are re-clothed in white boiler suits and the set replaced with a white antiseptic chamber.

The production marks the official start of Rupert Goold‘s tenancy as artistic director, and this opener certainly backs up his claim in the programme that he intends to make work that “asks big questions of plays, theatre and the world.” The sharp ensemble includes pertinent contributions to this end from Stephen Fewell, Christopher Patrick Nolan, Matthew Spencer and Mandi (formerly Amanda) Symonds and Gavin Spokes as Mr and Mrs Parsons.

See Also: Catherine Love – Can stage adaptations be too faithful?