”Sound of the Underground” at the Royal Court review – transgressive, confrontational and buckets of fun

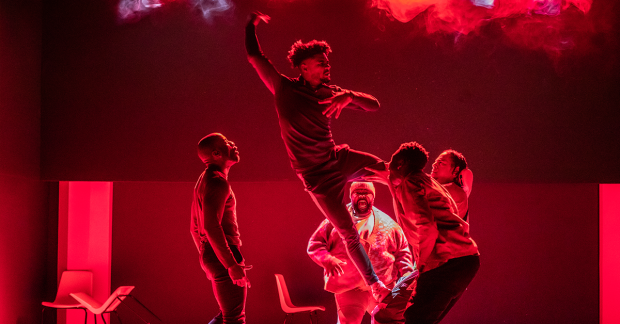

© Helen Murray

What an extraordinary work this is, not so much a play as a provocation, one that overturns traditional theatrical structures in order to make its points and leaves you full of questions – but smiling broadly at the same time.

Written by the non-binary writer Travis Alabanza and co-created with and directed by Debbie Hannan with contributions from all the performers, it takes the form of a take-over of the Royal Court by an octet of artists, emerging from the underground scene of London’s queer nightlife to proudly take their place centre stage. It’s deliberately transgressive and confrontational – but also gloriously funny, rude, and a celebration of the transformative power of art.

Its power springs from the personalities of its performers, who begin the evening by introducing themselves in front of a green ruched curtain which seems deliberately out of place. Their lines, which appear spontaneous but in fact are carefully scripted, introduce the idea that will sustain the entire evening: that these are artists who are emerging from underground because they have – as Tammy Reynolds as Midgitte Bardot puts it – “a lot of stuff we want to say about the state of art, our art, our world…and we are doing it in the most radical way…We’ve made a play!”

Then the curtain rises, on a conventional “kitchen sink” setting (designs by Rosie Elnile and Max Johns) which satirises the Royal Court’s reputation for realistic, political drama. Here the performers sit, plotting an action which turns out to involve the murder of RuPaul of Drag Race fame, who they despise for making drag sanitised and commercial, ignoring its radical roots.

Gradually the set too is dismantled in the frenzy of an imaginary war which is paused while the cast moan about their conditions, the under-funding of the arts in general, and pass around a bucket to raise contributions to supplement the £75 a show they estimate they are earning, which is even less than they get working in clubs and for hen parties.

This section ends with them lip-synching to their own voices, their concerns emerging – the way drag bars are closing even as drag’s popularity becomes more mainstream, the rise in homophobic and transphobic attacks even while people want drag acts as entertainment, the importance of queer culture as an exercise in reimagining and changing the world.

While this is going on, in a brilliant exercise in form meeting content, the set itself is being transformed into a cabaret, where Ms Sharon Le Grand brings the first half of the evening to a close with a fabulous rendition of “Sound of the Underground”. By the second half the stage is a curtained palace-like club, where the performers each perform a special number. Our sardonic compère Sue Gives a F**k, who has previously been very sharp on the subject of hen parties and their Prosecco habits, tells dirty jokes while offering a potted history of queer life down the ages.

The performances are a wonder, political and skilful, flamboyant and refined. Mwice Kavindele as Sadie Sinner the Songbird offers a burlesque dance on the theme of colonialisation; Wet Mess enters dressed as a baroque painting before rapping in Elizabethan garb; Lilly SnatchDragon’s striptease with fans is like a reinvention of Louie Fuller’s dances with coloured silks; Ms Sharon Le Grand turns the Cheeky Girls into an operatic aria, while Rhys Hollis as Rhys’ Pieces sings about the power of the club. Finally, drag king Chiyo breaks off in the middle of a striptease to express their fury that while their body is applauded in a club setting, on the street it makes them a target for violence that rainbow-flag waving does not protect them from.

It’s a direct challenge to the happily applauding audience, only marginally softened by a conclusion that once again asserts the beauty of fantasy and community. In its combination of bluntness and sophistication, this is not an easy show, or a smooth one. It doesn’t conform to any traditional notions of political theatre. But it is in its very bones something that feels new and timely, just as Alabanza promised.