Review: Leopoldstadt (Wyndham's Theatre)

© Marc Brenner

Towards the close of Tom Stoppard's epic and engrossing new play, he introduces the character of a gauche, slightly smug Englishman, who prides himself on his country's love of fair play and freedom, and regards his Jewish origins as "an exotic fact from my life gone by". Comic and crass, he is a semi self-portrait of the writer as a young man – one who didn't understand the tragic history of his family's Jewish past.

Leopoldstadt is the righting of that wrong, the undoing of that "fool's ignorance". Stoppard, as he explains in a touching essay in the programme, was born 82 years ago in Moravia, Czechoslovakia, as Tomas Straussler but was brought up as British and only really understood he was Jewish in 1993, when he met one of his surviving relatives and discovered that his mother and father's extended families had died in the Holocaust. He uses two real events – the drawing of a family tree, and the healing of a scar – within the drama.

But it is not an autobiography, rather an imagining of the story of the Merz family, textile magnates in Vienna, whom we first encounter in 1899 in prosperous splendour, when their money is buying them access to the highest reaches of society and finally see in 1955 when time and Hitler have done their worst and a bustling, lively clan are reduced to a few lucky survivors.

It's a world contained in a single room. Because this is a play by Tom Stoppard, the sweep of the work – brilliantly captured in Richard Hudson's stylised setting which moves from a suggestion of ornate grandeur to bleak decay – encompasses the setting up of the Jewish state, the intellectual life of Vienna, mathematics and the dream theory of Freud. Sometimes it is too much; there are many lessons of history to absorb.

But its heart is the family. Even here, the size can be baffling. There are 26 actors and 15 children on stage, playing many more characters through generations. The start of each act involves a certain amount of gear crunching, as you simply try to work out who is who and how they are related. Yet I think that is part of Stoppard's point. The aching centre of this play, its great plea, is that it is important to try to remember and to understand; what people recall and what they forget matter both in terms of society and the family home.

"You live as if without history, as if you throw no shadow behind you," one character reprimands the callow Leo. The play argues that this is impossible. It opens and closes with two family portraits, one full of presence and one of absence and is tightly structured around three great scenes of naming: one in the opening section where the grandmother goes through the family photographic album, musing that "you don't realise how fast they're disappearing from being remembered"; the next in 1938 when a Nazi civilian calls a roll of family members before evicting them from their apartment; the final an unbearable toll of remembrance.

It's held together by other themes too, not least what it is to be Jewish. In the opening sections, Hermann, the sophisticated head of the factory, played with extraordinary charismatic sensitivity by Adrian Scarborough, registering each flicker of feeling and thought down 40 years of his character's life, is full of pride and hope about his assimilation by society. He has converted, has married the Catholic Gretl (another wonderful tensile performance down many years by Faye Castelow) and his son Jacob has been baptised and circumcised on the same day. The play shows the limits of that assimilation and asks why that is, stretching its arguments into ways that ask questions about tolerance and prejudice down the years.

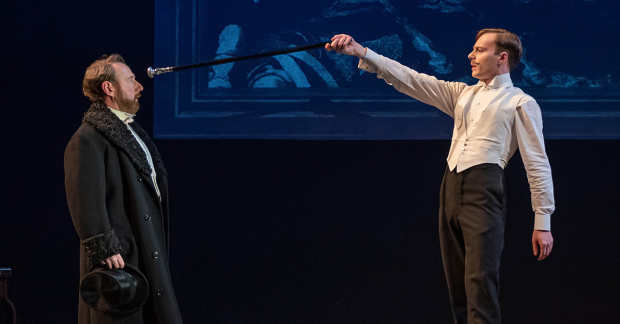

It asks other questions too: the limits of art – "barbarism will not be eradicated by culture," says a kindly doctor, describing the philosophical paintings of Klimt; the limits of politics. It is incredibly rich, packed with ideas. Patrick Marber's clear, direct production finds the lines of thought, and they seem to be embodied by the shifting tones of Neil Austin's sensitive lighting. Although the performances do not all yet absolutely gel (some people have quite a lot to do) there is outstanding and emotionally devastating work from Luke Thallon (in two roles, including Leo) and Sebastian Armesto who also makes the most of two contrasting parts. Ed Stoppard, the playwright's son, provides a gentle cameo.

It's an evening that leaves many people in tears. It left me profoundly moved but also full of thought and understanding. If it is Stoppard's last play, as he seems to imply, it is a very fine testament to all he has given and all he has learnt.