Robert le diable

week has been the late departure of the lead soprano from the Royal Opera’s new

Robert le diable, when it should have been the revival of

Meyerbeer’s grand work after a 120 year absence. Putting aside the gossip and speculation as

to what happened in the rehearsal room, as well as the earlier casting issues

that have bedevilled the production, let’s focus on the real event.

Giacomo Meyerbeer was the most

celebrated opera composer of his day, enjoying enormous success with this and a

handful of other works, but his reputation diminished rapidly after his death,

not least once his protégé Richard Wagner got his fangs into him. In the twentieth century he was almost

unperformed; one could have been a regular operagoer for 40 years in this city

and hardly had an opportunity to see his work, making this major revival a

must-see for anyone wanting to go beyond the usual limited repertoire.

A four and half hour opera, famed

for its grandiloquence and over-blown gesture, is a forbidding prospect, even

for the most hardened, so the appointment of Laurent Pelly as director, known

for his whimsical, broad-comedy approach, might have been an attempt to soften

the blow. He lightens and simplifies but

in the process strips the opera of its epicness. Long stretches of just two or three

principals on stage calls out for some extraneousness and the sparseness causes

the evening to drag.

When Pelly rises to the chorus

scenes, it’s certainly colourful with a strange mix of styles. In an almost surrealistic opening, a mass of

men in armour, (along with a bear) inhabit a café over-looked by mutli-coloured

model horses. The theme is carried

through to the ladies-in-waiting of Isabelle’s court, brightly-daubed from head

to foot, but then dropped, as a stylistic hotch-potch takes over. Act 3 has the most stirring visuals, with a

Gustave Doré-inspired background of engraved mountains with natty projections

that effectively evoke a hellish realm.

Pelly increasingly acknowledges

that this is ultimately a creaky work peopled by blood and thunder villains,

flawed heroes and pure women. In the

final act, the most literal of staging devices seems to be mocking the

simplicity of Meyerbeer’s dichotomy, as Robert is torn between good and

evil. Hammer horror takes over in the infamous

dancing zombie nuns scene (no joke, that’s how it’s written). The supernatural was something of a trend in

1831, following the success of Der Freischutz a few years

earlier. These nuns could be a lot ruder

(what would Ken Russell have done with them?) but it’s elegantly choreographed

and certainly brings things to life, in every sense, halfway through a long

evening.

Meyerbeer’s score is rich and melodic,

with ample opportunities for virtuosic singing.

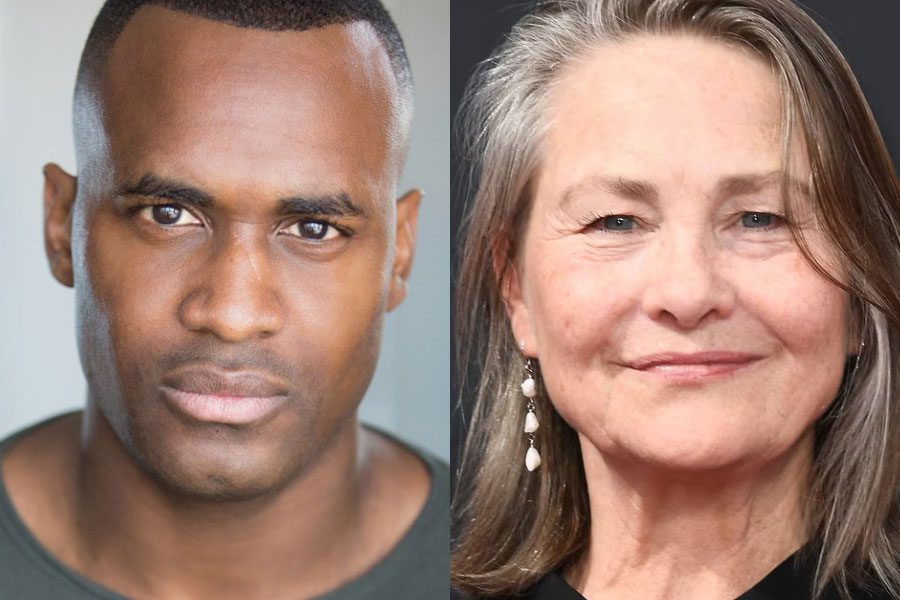

Patrizia Ciofi, who took over at just a few day’s notice, is

astonishingly good and Bryan Hymel, who impressed in the year’s other French

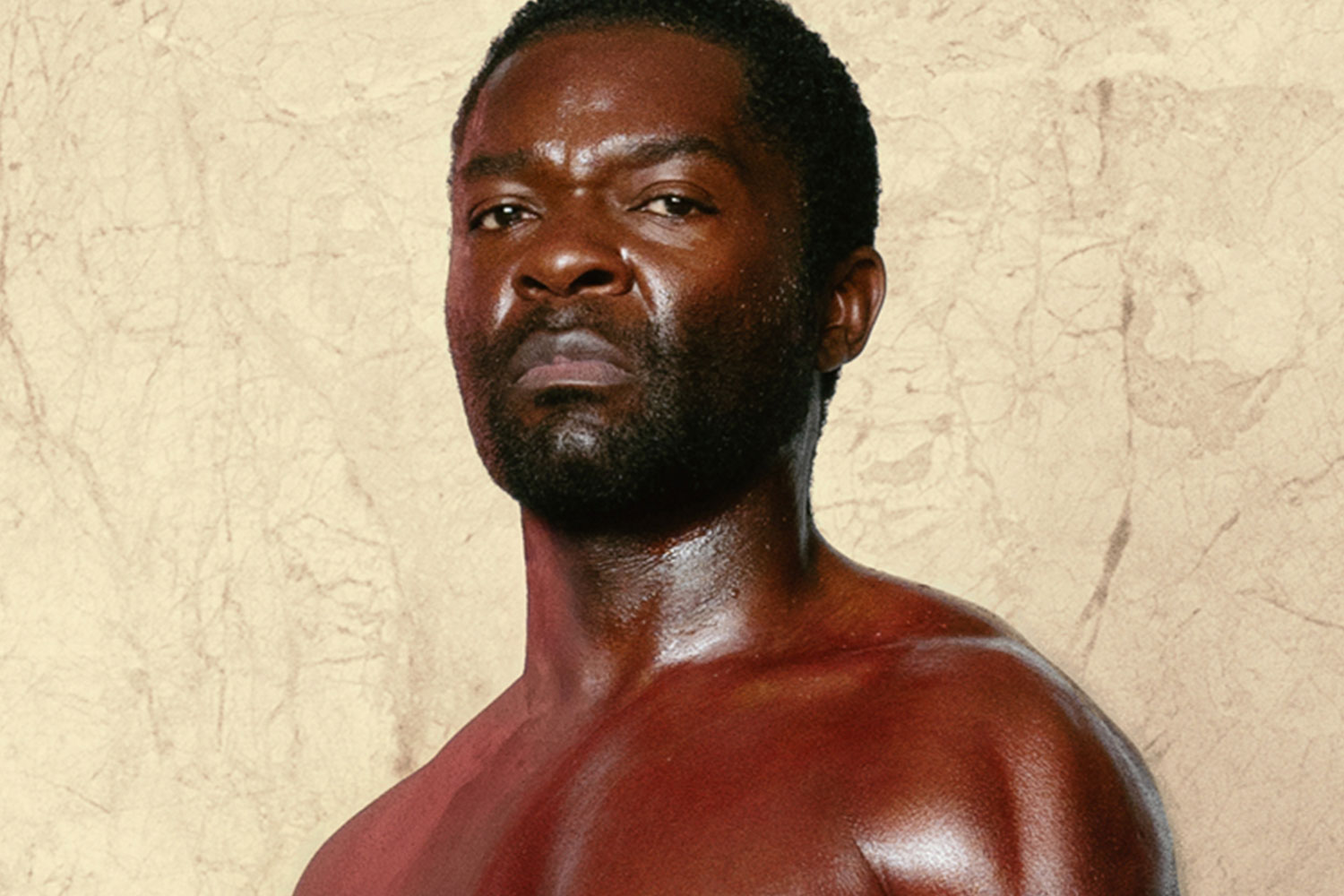

blockbuster Les Troyens is similarly heroic here as Robert. John Relyea is a black-voiced baddie and

Marina Poplavskaya, whether you like her or not, delivers. Smaller roles are ably filled, from Jean-François

Borras’s resonant Raimbaut to a batch of knights and heralds sung by Jette

Parker Young Artists.

Daniel Oren conducts with finesse

and makes this a worthwhile outing but one you

may not want to repeat.

– Simon Thomas