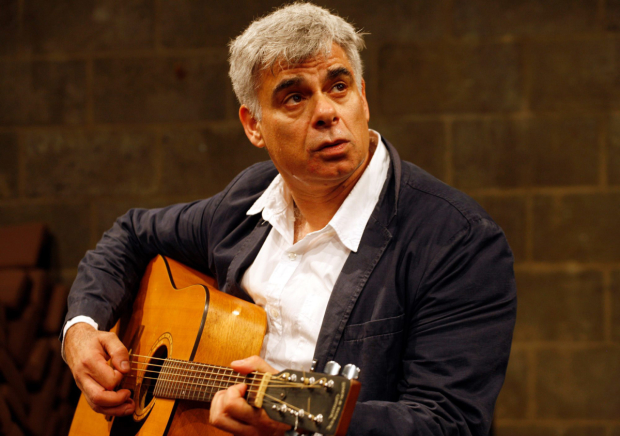

Review: Living with the Lights On (Young Vic)

© Simon Annand

It was by the banks of the River Avon that Mark Lockyer first met the devil. He was halfway through a Stratford season, playing Mercutio in an RSC production of Romeo and Juliet, when an American tourist going by the name of 'Bees' invited him to take a trip to hell.

Bees might have been a product of Lockyer’s mind, but there’s no doubt the actor took that trip to hell over the next few months. In this confessional solo show, 20 years on, the middle-aged actor recounts the complete unravelling of his mental state. What starts with stage fright and an impromptu saxophone solo in the middle of the Capulet ball just after a break-up ends actor forcibly committed as a danger to himself and to society. It goes to show just how fragile our minds can be; how easily sanity can give us the slip.

Lockyer is an engaging and energetic raconteur, and, in many ways, he makes mental illness seem a real blast. Telling this story from his own perspective, Lockyer makes a kind of sense of his increasing insanity. He skates over the oddities – £350 spent on flowers for a first date or a stage manager’s note that he’s started to smell – and rattles through one hilarious anecdote after another.

What you notice instead is the feeling and intensity of every experience. Lockyer bursts through events like a human adrenaline shot. It’s like he lives life in italics, everything maxed out. He tumbles through events, hurtles from one incident to another. Life’s a blur, a runaway train. Lockyer beautifully conveys the sheer momentum of manic depression. He knows something’s not right, but his checks are bouncing, his balances are off and his brakes have all but broken.

There are, of course, all these telltale signs – every one of them missed. They must have seemed like eccentricities to others, I suppose, but taken together they make an alarming picture of a man in distress. There were the 17 saucers of "holy water" a company landlord found dotted around his bedroom or the time he sat, shoeless, in a travel agent booking next-day flights to Skiathos. Lockyer’s onstage "antics" in Stratford might have rung alarm bells, but you’d expect trained medical professionals to take suicide attempts seriously. Yet Lockyer’s let go after swallowing 80 paracetamol and again after attempting self-immolation. No beds. No time. No care.

The only person in possession of the full picture is, of course, Lockyer himself – and he’s hardly the sanest of judges. The form intensifies that and, as Lockyer bounces into impersonations – each a masterful little caricature – you get a real sense of him: an actor who seems to contain multitudes; a man who sees through people, simplifies them and sorts them into types. How, then, does he keep a hold on his own complexities and contradictions?

Occasionally, the tone strays into self-help presentation, but Ramin Gray‘s staging is deceptively casual. The bare stage is lined with bits of the theatre space – a stack of seating, a rack of stage lights – and it’s a mark of how easily anything can come apart. Life isn’t a polished performance, but a process. To get through it in one piece, we have to take care of one another.

Living with the Lights On On runs at the Young Vic until 23 December.