Urinetown (St James Theatre)

© Johan Persson

Urinetown The Musical, like Avenue Q, Spamalot and The Book of Mormon, is an ironic, subversive musical that is clever enough to have it both ways, have its cake and eat it, take the rise out of the genre and contribute a parody-like sophomoric advance at the same time.

And everything about Jamie Lloyd's production at the St James is geared to pointing up the parallels with The Threepenny Opera and Les Misérables in its brutally sharp telling of greed and corruption in the world of Urine Good Company big business while the people rejoice in the sewers and learn to be free to pee.

The only thing missing from the music and lyrics of Mark Hollmann and Greg Kotis is anything like a melody or a truly great song, something of a fault in a musical, I admit, and for a show that is primarily satirical, it’s not really all that funny.

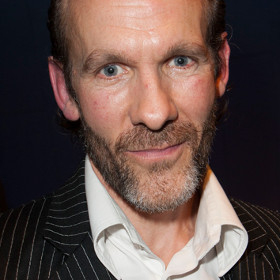

But nobody’s broken this news to the cast, who set about their communal task with fervour and a fanaticism that’s almost frightening. The situation is laid out by RSC star Jonathan Slinger as a no-nonsense Officer Lockstock (the other cop’s called Barrel) in "Too Much Exposition": the toilets have been privatised in a water shortage and public expressions of relief outlawed.

It’s a privilege to pee, sings Jenna Russell‘s Mrs Lovett-like urinal manager, Penelope Pennywise, while Simon Paisley Day‘s grim-featured president of the urinal monopoly, Caldwell B Cladwell, jumps into bed with the politicians and policemen to suppress the townsfolk before they come out of the water closet.

Love, naturally, finds a way in the romance of Cladwell’s daughter, Hope (Rosanna Hyland), a hostage to fortune and the cause, and the muscle-flexing, valiant man of the pee-people, Bobby Strong (Richard Fleeshman); the uprising has to work its way tortuously through the sewers as well as a series of negotiations and stand-offs that result in the utopian delusion of unprotected amenities and rivers of free-flowing, well, water.

I first saw the show in New York over ten years ago at the rackety Henry Miller Theatre, before it was rebuilt and then re-named the Stephen Sondheim. It had a downtown, improvisational air and naughtiness about it that has been transformed by Lloyd and his designer, Soutra Gilmour, into a slick, formulaic and virtually heartless spectacle, stunningly well performed on a split-level set.

So while the end result is highly impressive, it does not invite any kind of warmth or delight in the audience. It’s so busy sending up conventions of both Brecht and Broadway that it forgets to reveal its own true purpose then tries to redeem itself by disowning the habit of idealism and granting Cladwell the economic and political high ground in the effectiveness of his tyranny. Freedom’s a chimera and rebellion so much pissing in the wind.