Michael Coveney: Reflections on Rik Mayall as David Hare reopens Skylight

© Dan Wooller

The comedian Rik Mayall, who died suddenly on Monday, aged 56, was best known for his outlandish performances in the television anti-sitcom The Young Ones, as Mad Gerald and Lord Flashheart in Blackadder with Rowan Atkinson and Stephen Fry, and as the cravenly repellent Tory MP Alan B'Stard in The New Statesman.

But to what extent were these larger-than-small-screen performances the ravings of a maniacal stand-up comedian, or the brilliant inventions of a seriously talented comic actor? The answer is, surely, they were both, and it's interesting that almost everything he was in – apart from The Young Ones and Blackadder – found its way on to the "live" stage.

There were extensive national tours with his friend Ade Edmondson in both Ben Elton's Filthy Rich and Catflap (Mayall was an obstreperous television comedian flanked by his minder and his agent, played by Edmondson and Nigel Planer) and in his and Edmondson's Bottom, as well as a West End bow for B’Stard in The New Statesman, written by Laurence Marks and Maurice Gran.

He was always, mostly, himself, to the power of several extra megawatts: Marks and Gran said they wrote B'Stard merely by shoving Rick in The Young Ones into a pin-striped suit. So this process of transferring himself to the stage was slightly different from how Rowan Atkinson sidled into a Michael Frayn and Chekhov bill some years ago and Simon Gray's Quartermaine's Terms more recently; or how Lenny Henry has stormed the "legit" heights as both Othello and Troy Maxson in August Wilson's Fences; or indeed Nigel Planer in various musicals, including Charlie and the Chocolate Factory.

But, like them, Mayall also cast aside his comedy persona to play "straight" theatre, and was a huge success between 1985 and 1991: as a scarily unstable, abrasively unfunny Khlestakhov in The Government Inspector directed by Richard Eyre at the National (Jim Broadbent was the Mayor); as a genuinely wistful and mournful Vladimir in Waiting for Godot, directed in the West End by Les Blair (Ade Edmondson was Estragon); and in two Simon Gray plays, a revival of The Common Pursuit, and as an Irish petty criminal who befriends the spy George Blake in prison in Cell Mates.

The latter, of course, was the play Stephen Fry walked out of three days after the first night and booked a one-way ticket to Belgium. Honestly, Belgium! The reviews were bad, but not that bad. The play, fatally wounded, staggered to an early bath, but after the initial kerfuffle and slanging matches, everyone calmed down and just about made up thereafter. But Mayall never played another stage role.

There's a theory that after his quad bike crash in 1998, he was never quite the same again, developing the epilepsy that might have caused his death (no confirmation forthcoming yet), but most of his friends and colleagues have been as mystified by his demise as they are upset.

I think he was a really fine actor, but he was a great personality, too, and preternaturally funny, and that was what made him different. After the accident, he was in a coma for five days, and claimed that he'd done much better than Jesus, who only rose from the dead after three. As he came round in hospital, he said to the first doctor he saw, "So, you're the bastard who keeps sticking needles into me." Ave atque vale, as some pseudy prat of a poet called Catullus once said.

David Hare on the playwright's life

David Hare always gives good interviews, and in a recent conversation with film producer Peter Ansorge at the Charleston Festival, Sussex home of the Bloomsbury set, he said that being a dramatist is a corrosive business; he would never recommend anyone to spend a night with John Osborne, Harold Pinter or Tennessee Williams. Does he include himself in that company of malcontents, I wonder?

He also said he didn't understand why anyone would be against Great Britain being part of Europe, as so many of our forebears died on their battlefields. He grew up and went to school in Sussex and always felt France to be very near, and talked of directing Shaw's Heartbreak House, in which the great storm of the First World War looms over the last act. Shaw had written the play in an English garden where he could hear the distant bombing.

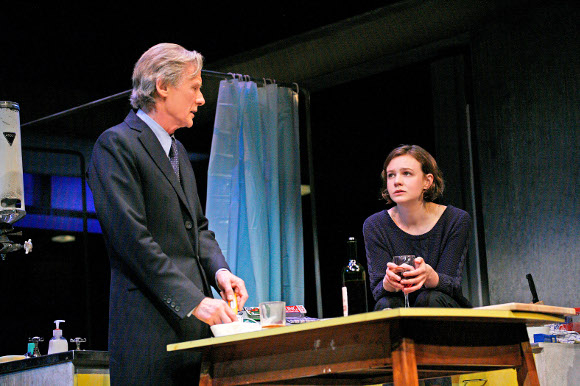

With Skylight opening next week, he was asked by a Guardian reader in a Q&A about collaboration: "The more you work with the same people, the more you raise each other's game." Skylight is directed by Stephen Daldry (their fifth collaboration), designed by Bob Crowley (their ninth) and stars Bill Nighy (their tenth). If nothing else, Carey Mulligan should stop them all becoming too cosy with each other, too. And the set looks like a stunner.