Why don't more visual artists design for theatre?

Matt Trueman looks at why the art world and theatre world don’t collide more often

© Robert Altman

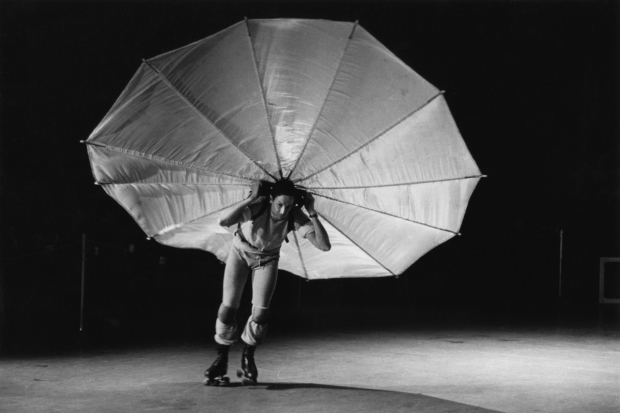

The other day I went along to the Robert Rauschenberg retrospective at the Tate Modern. In amongst the screen prints and combines, there are snatches of performance, projected on the walls. For years, the American worked with choreographers like Merce Cunningham, Paul Taylor and Trisha Brown, creating sets and costumes, later choreographing his own pieces. (One of his, famously, involved two winged rollerskaters circling a trained ballerina rather clumsily.)

Visual art tends to keep itself separate from theatre these days, so Rauschenberg’s designs intrigued me. One, Cunningham’s Minutiae, had six dancers in chalky tie-dyed leotards leaping through a colourful sculpture. He often created his sets live, using found objects and sounds – a process he called "live décor," which fed back into his solo practice. One of his combines, First Time Painting, was created live onstage at the American Embassy in Paris.

It makes sense that he’d be drawn to performance. It is, in a sense an amalgam art-form: shape meets sound; bodies, light; movement, words; time, space. The stage is arguably the ultimate mixed media space and Rauschenberg might be the ultimate media mixer. His early treasure troves, his combines, his screen-print collages and his machine sculptures, all of them are about combinations. What’s his tub of mud doing, as it bubbles away to a soundtrack on loop, if it’s not somehow dancing?

'Stage design works through signs and through space. But what might visual artists make of that space?'

One of his designs is particularly striking. Created for Trisha Brown’s piece Glacial Decoy , it takes over an entire wall in the Tate Modern: four panels containing a ticking slideshow of black and white photos. The images move left to right. A motorbike. A plinth. Some cows. A curtain. Tree roots. And so on. Each is its own distinct image, but together, they set your synapses firing. Your eye spots shapes and shadows that repeat. Your brain scrabbles for connections. You feel this design. You don’t just look at it. You live it.

(© Photo: Peter Moore © Barbara Moore / Licensed by VAGA, NY. Courtesy of Paula Cooper Gallery, New York ))

It made me wonder why we don’t see visual artists in theatre. Set design is an art-form in its own right, for sure, and its best practitioners are attuned to the particular way that the theatre makes meaning. Stage design works through signs and through space. But what, I keep wondering, might visual artists make of that space?

Plenty have worked in theatre in the past. Picasso created backdrops for the Ballet Russes, and Dali did the same for opera. Edvard Munch designed many of Ibsen’s plays, returning to his work in sketches over and over. (Stephen Unwin’s production of Ghosts took his designs as its starting point a few years ago.)

'Contemporary artists treat theatre with scepticism or even suspicion'

These days, though, it’s comparatively rare. David Hockney worked at Glyndebourne in the mid-seventies momentarily, and Tracey Emin assembled a few works – well, replicas – into a fringe production of Jean Cocteau’s Les Parents Terribles in 2004. Antony Gormley collaborated with the choreographer Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui on Sutra, delivering a stage full of pillars and plinths.

Mostly, though, contemporary artists treat theatre with scepticism or even suspicion – surprising when you think how performative their work can be. Obvious examples, but the flies hatching and dying in Damien Hirst’s A Thousand Years are performing and the Chapman Brothers’ hellish dioramas are essentially stage model boxes. The attitude, though, was caught by Marina Abramovic: "To be a performance artist, you have to hate theatre." It is, she explained, too fake to be truthful.

'Visual artists might reshape the concept of and the sensation of sitting in the theatre'

Cough, cough, bullshit. In any case, fakeness has its own reality. Ragnar Kjartansson’s Barbican exhibition showed as much. It included his model boxes for a knowingly sentimental, "over-romantic" opera staged at the Volksbühne. Der Klang der Offenbargung des Göttlichen (The Sound of the Revelation of the Divine) showed empty landscapes beneath swirling strings, an ironic reclamation of 19th Century pictoral music plays that got rid of actors. Kjartansson has also staged two minutes of Mozart’s intoxicating final aria from The Marriage of Figaro on a loop for 12 hours – a piece he called Bliss, an overdose of beauty.

This is what visual artists might do: reshape the concept of and the sensation of sitting in the theatre. As visual art becomes more experiential – think Gormley’s mist-filled Breathing Room – theatre designers are going the other way. Jeremy Herbert, who incorporates immersive elements into his sets, exhibited at Frieze and Es Devlin built a mirror maze installation (an echo of The Nether set, perhaps) in Peckham last year. Wouldn’t it be interesting if visual artists came the other way?