The RSC's original home was born in the ashes of a crisis – with the help of a woman unable to vote

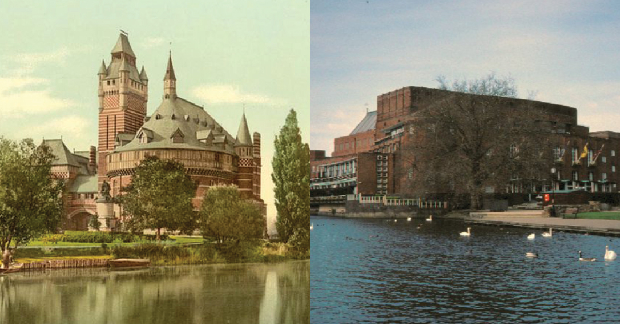

© Left: Snapshots Of The Past / CC BY-SA (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0), right: David Stowell / Stratford-upon-Avon

It is not entirely clear what started the flames – some speculate it was an electrical fault or simply a lit cigarette end dropped that day. What is known is that on 6 March 1926, just weeks before the summer season was due to begin, a fire destroyed the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre in Stratford-upon-Avon.

As the flames raged, a human chain was formed among staff and public to remove all books, costumes and paintings from the theatre. Thankfully no human was killed during the disaster although two horses drawing fire engines from Warwick died from exhaustion. Even the theatre cat managed to escape with eight of its lives intact.

The company's (then known as the New Shakespeare Company) search for a temporary home began immediately and a new space was found at Stratford's local cinema. Dressing rooms were added and the stage was extended in order that the season could open on schedule, a remarkable feat given the scale of the disaster.

The company could not remain there permanently however and over the next few years, significant fundraising was completed for the rebuild that would take place. Thomas Hardy and George Bernard Shaw were two prominent writers who made contributions. Funnily enough, Shaw had been a major critic of the 1879 theatre that now lay in ruins, but this did not stop him from donating in the theatre's moment of crisis.

There was an open competition to determine the new theatre's architect, which saw 71 applicants send in designs from around the globe. The final shortlist consisted of three Americans and three Brits, one of whom was the sole female finalist, Elisabeth Scott. At this moment in history, less than 100 years ago, unmarried women under the age of 30 were barred from voting in the UK – if Scott won, she would become the first woman to design a major British building but remain unable to vote. It speaks to the bravery and perseverance of suffragettes that this law was changed by the time Scott was decided as the final winner and her design had come to life.

The winning blueprint itself had been inspired by her past trips to Germany and offered art deco detailing rather than the more traditional Tudor and gothic style of the old theatre. She also wanted the public to feel at ease in the new building, as well as boasting a fantastic auditorium: "Acoustics and sightlines must come first. At the same time I have taken full advantage of the exceptionally beautiful site on the banks of the Avon".

Six years after being destroyed, the new theatre opened on Shakespeare's birthday, 23 April 1932. Performances of Henry IV Part I in the afternoon and Part II in the evening celebrated Scott's new space which was roundly praised by newspapers. She would have further success in her distinguished career but arguably none as lofty as this, and the Scott Bar on the current site serves as a testimonial to her ingenuity and skill.

Like many theatres now faced with an unprecedented challenge, the RSC has no obvious way to defend against the coronavirus. This is a different situation to 1926 – the theatre company cannot simply start over again. Instead they are showing a different kind of strength and creativity to realise that a strong virtual presence is the best they can do right now. Making filmed RSC productions available with Marquee.tv and the BBC is significant. These initiatives will keep Shakespeare's work alive whilst the theatre that bears his name is closed.

This article was made possible thanks to the knowledge and generosity of David Stevens, who has worked with the RSC for over ten years.