The Maids at Donmar Warehouse – review

Kip Williams adapts and directs Jean Genet’s 1947 classic

Kip Williams’s adaptation of Jean Genet’s claustrophobic chamber piece The Maids arrives at the Donmar Warehouse following the international acclaim for his take on Wilde’s Dorian Gray, which saw Sarah Snook multiply across screens and mirrors in a dizzying exploration of self and celebrity.

Here, he applies a similar video-heavy aesthetic to Genet’s 1947 text, which follows two sisters who plot to murder their employer, the glamorous Madame. That premise has been transposed into a modern influencer bubble. Madame, played with brittle poise by Yerin Ha (soon to appear in Bridgerton), is a social media star whose carefully curated image teeters on the edge of collapse after her boyfriend is accused of a crime – as part of a trap engineered by her own maids, Solange and Claire, played by Phia Saban and Lydia Wilson.

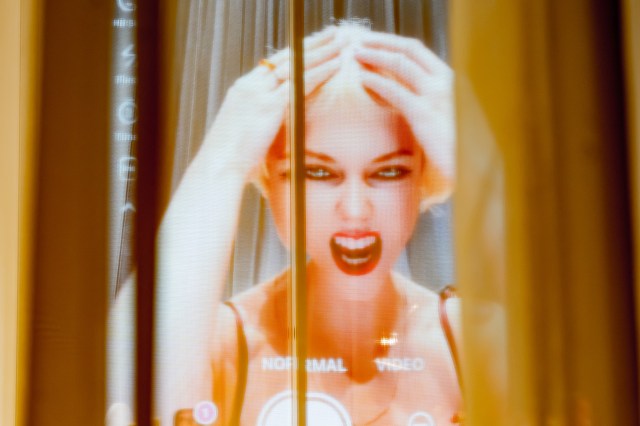

What unfolds is a tightly wound, high-decibel psychodrama, full of raised voices and rapid-fire emotion. Smart phones are brandished by the performers as their images are projected on vast, mirrored screens that dominate the space. In theory, it’s an ideal match for Genet’s feverish role-play, in which the maids, Solange and Claire, repeatedly act out the murder of their mistress, the Madame – just as we in our Instagram-swaddled ways ritualistically post curated content to our grids, expecting affirmation with added hashtags.

Rosanna Vize’s hyper-realised set and costumes do much to anchor the production. Her vision of the Madame’s world is one of oppressive excess: carpets crawl up the walls, peonies and chrysanthemums are stuffed into scores of vases, and the Donmar’s compact auditorium feels almost inescapably stifling. It’s an environment that mirrors the psychological trap of servitude, where beauty itself becomes suffocating.

The production is, without doubt, a feast of bells and whistles – technically immaculate, visually audacious, and conceptually dense – but that polish sometimes comes at the expense of intimacy. The performances, though bold, brash and captivating, often feel dwarfed by the machinery surrounding them. We see every twitch, every tear magnified, yet rarely feel the rawness beneath. It’s always arresting, but never quite transporting. Snapchat filters snuff away the sense of genuine connection.

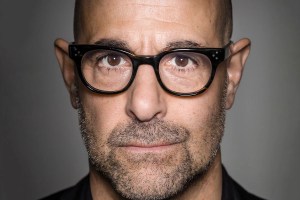

Performances are suitably adept. Saban and Wilson hurl themselves into the roles with frenzied commitment, their energy matching the restless momentum of Williams’s video-led staging. Wilson in particular delivers a monologue masterclass in a chameleonesque opening sequence, as her accents slips haphazardly across English-speaking nations. Ha, arriving late to the party, makes an instant impression as the Madame, loathsome and likeable with disconcerting ease.

It often feels like watching a live feed of the internet itself – a cascade of competing images, emotions and identities that never quite lets you breathe. That’s apt, in a way. The piece becomes a reflection on how social media turns status into performance, friendship into currency and self-worth into statistics. When Solange tells her mistress, “You have so many friends – 28.4 million of them,” it lands as both satire and tragedy.

Where Dorian Gray succeeded, this Maids sometimes falters. The former had a sense of narrative propulsion – a forward motion that carried the audience through its many distorted worlds. The Maids, by contrast, is static and cyclical, bound to one room and one ritual. It’s a suffocating structure by design, reflecting the sisters’ lives, but it can leave the evening feeling stymied and awkward. Whereas Dorian Gray was gracious and ferocious, this feels airless, punishing – and perhaps deliberately so. Amongst all the chatter, the show doesn’t feel like it truly shows its teeth.

Yet there are moments when Williams’s approach finds a strange, unexpected poetry: when the screens freeze on the tormented sisters’ faces, spliced by partitions in the mirrors , or fleetingly hint that, perhaps, the duo’s plan may finally come to.

If The Maids never fully coheres, it nonetheless reaffirms Williams as one of the most distinctive directors working today. And it bodes well for Dracula, which he brings to the West End next spring – a story whose gothic ferocity may suit his brand of visual and psychological dissection far better. For now, though, The Maids feels like an experiment admired more than loved: a lavish, looping dream. Bells and whistles are all well and good – but sometimes they just add to the noise.