The Baker’s Wife review – a subtle and delicate confection for the London stage

The Stephen Schwartz musical runs at Menier Chocolate Factory until 14 September

With Wicked, Pippin, Godspell and the stage version of The Prince of Egypt, Broadway’s Stephen Schwartz may have produced more varied and majestic scores than this adaptation of a whimsical 1938 French movie, but The Baker’s Wife probably represents his most subtly complex and enchanting work.

The original production in the mid-1970s was a notorious mess that never got to New York while Trevor Nunn’s 1989 London premiere was lovely but lacked the requisite lightness of touch. American director Gordon Greenberg gets the balance between lush romanticism and wry humour mostly right in this richly enjoyable new version for the Menier, overlaying it with heartbreak, sultry atmospherics and an unmistakable erotic charge.

The first thing you’ll notice is the set. Designer Paul Farnsworth has had a French field day turning the Menier auditorium into a rural village square: locals play boules on the green or shelter under an ancient tree, ivy entwines wrought iron balconies in front of shuttered windows on all sides, villagers and audience members sit at café tables, and an antiquated boulangerie sign and old-fashioned street lamp dominate the scene. The sense of immersion into an idyllic other time and place is delicious, and lighting designer Paul Anderson bathes it alternately in the golds and ochres of summer sunlight or the cobalt blue of night. It’s a ravishing eye-full, so much so that it’s almost possible to overlook how thin the story and characters are.

Joseph Stein’s book matches the languid pace of Marcel Pagnol’s screenplay. What it lacks in dynamism it makes up for in eccentric charm, and it has a biting wit that stops this story of an ageing baker who downs tools when his younger wife dumps him for an even younger local hunk, much to the consternation of the bread-crazed villagers, from becoming saccharine. Only in France would the collapse of the boulangerie be viewed as a catastrophe, but a magnificent cast play it with such relish that it’s easy to get involved.

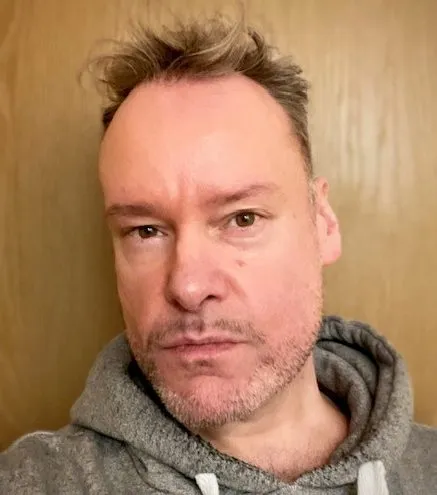

Clive Rowe invests the appropriately named baker Aimable with such kindly effervescence that it’s painful to watch it being taken away from him. His bereft second act solo, the haunting, minor-keyed “If I Have to Live Alone”, is the emotional lynchpin of the piece and is more moving because Rowe doesn’t play the easy sentiment. Genevieve, his wife, is underwritten but Lucie Jones gives her spirit and potent sensuality. Her version of the show’s most famous number, the soaring “Meadowlark”, really a three-act play in aria form, is a tour de force of acting through song but builds organically to its roof-raising climax; the tone of the musical performances throughout is more conversational than grandstanding, which is unfashionable but refreshing. The score is really an American showbiz take on French music but has authentic sparkle and grace, plus moments of Mediterranean heat, and Schwartz’s lyrics are heartfelt.

Another highlight is “Chanson”, the lilting anthem to monotonous contentment (“every day as you do what you do every day, you see the same faces who fill the café…”), which opens the show then recurs periodically. lt’s delivered entrancingly, with subtly Gallic vocal timbre, by a luminous Josefina Gabrielle as the all-seeing café proprietress who acts as a warm, wisecracking sort-of commentator whilst in permanent conflict with her irascible husband (Norman Pace).

Stein’s writing is broad but the company does a stellar job of filling in the details, creating a credible community on stage. The petty squabbles, long-term feuds, mutual affections and putdowns feel joyously real, and the villagers are a funny, infuriating, engaging bunch. Choreographer Matt Cole has them moving en masse or dancing like real people rather than showgirls: his work here is a million miles away from his award-winning Newsies, but it’s excellent.

Sutara Gayle’s judgemental spinster, Finty Williams as a bullied wife, David Seadon-Young’s tactless but well-meaning village drunk and Matthew Seadon-Young (yes they’re real-life brothers) as a manic priest, all register strongly. Michael Matus’s ennobled roué, flanked by his trio of “nieces”, is a fabulous comic creation, incorrigible yet likeable. Joaquin Pedro Valdes as Dominique, the confident young buck who lures Genevieve away, exudes star quality and careless sex appeal. Although at times he seems to be in a different show from everybody else, he sings thrillingly and has combustible chemistry with Jones. It’s unhelpful that their second act duet “Endless Delights” is cut as it fleshes out their relationship; as it is, these key characters disappear for much of act two.

Currently, Greenberg’s technically ambitious production is tonally inconsistent and sometimes lacks urgency: it feels as though it needs slightly longer to bed in. However, with its luxury casting and lush visuals, this satisfying, delicate confection is already a heady delight.