Tambo & Bones at Theatre Royal Stratford East – review

Matthew Xia’s production runs until 15 July

Philadelphian writer Dave Harris’s play (he is also an acclaimed poet), which was first performed Off-Broadway last year, opens in an idyllic but artificial rural setting (Bones rolls his eyes at such ‘fake-ass nature’) accompanied by folksy banjo music. It’s a riff on the ‘traditional’ minstrel show in which the characters are defined by their laziness and gullibility, with added swearing (certain words are used in a way white people would never dream) and modern asides. “This is not Hamilton,” they note wryly.

The sense of absurdity and the costumes are straight out of Waiting for Godot. It’s very leisurely and contrived but the tone shifts when a knife comes out. The minstrel show, which originated in the nineteenth century in which white performers in blackface enacted racist stereotypes, has astonishingly only been obsolete in the UK for about 35 years. The Black and White Minstrel Show was a staple of the BBC’s prime-time light entertainment schedule from 1958 to 1978 and a stage version that toured holiday resorts lasted until 1989.

There are dynamic performances by Rhashan Stone and Daniel Ward as the two protagonists who embody contrasting archetypes. Tambo is the intellectual idealist who wants to change the world through inspirational speeches and sociological jargon, and keeps trying to deliver a treatise about race relations in America that Bones tells him no one wants to hear. Bones, the entertainer, initially appears rather dim but is actually an ambitious businessman (he tells a sob story about being homeless as a child with his cancer-stricken single mom before revealing that it’s all made up). In the present day (‘from sleep to woke’), the duo’s fame, fortune and power as rap stars eventually leads to world domination in which Tambo and Bones become the founding fathers of a new world order (spoiler: genocide is never the answer).

I admired the ambition and uninhibited nature of Harris’ writing and the energy of Matthew Xia’s exuberant production but much of the humour that had swathes of the audience in stitches left me slightly bemused (admittedly I respect rap music but can’t say I enjoy it regularly). All of this is absolutely not a criticism – there’s no shortage of shows aimed at white people and the manufactured outrage around the fact that a ‘Blackout’ performance is being held for one performance out of about thirty has been infuriating to witness.

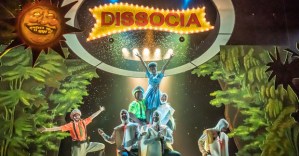

The production features some dazzling stagecraft in the form of Sadesya Greenaway-Bailey and Ultz’ set designs that showcase both old-fashioned artifice and contemporary urbanism. The lighting and sound design by Ciaran Cunningham and Richard Hammarton respectively contribute to a party-like atmosphere, though anyone who experiences from sensory overload might want to tread carefully.

It breaks one of the few sacred rules of theatre, which is that a two-hander (albeit one supplemented with two white robots enacted by Jaron Lammens and Dru Cripps in the short final section) should never exceed 90 minutes, no interval.

There’s no curtain call and a standing ovation is enacted to an empty stage – hopefully the performers can experience the appreciation from the wings.