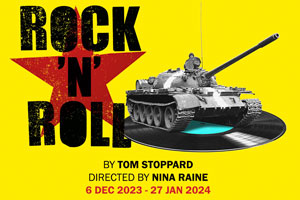

Rock ‘n’ Roll at Hampstead Theatre – review

The Tom Stoppard revival runs until 27 January in the Upstairs space

When Tom Stoppard’s Rock ‘n’ Roll was first produced at the Royal Court Theatre in 2006, the UK was engaged in drawn-out conflict in the Middle East, Labour were in power, and the nihilistic optimism of the play’s bopping ending might have felt bolder than it does now. At the Hampstead in late 2023 in a new production directed by Nina Raine, it feels like a programming less engaged with the current moment than you might expect. This is a dense but accessible play (or it should be), its intergenerational narrative of trades (in romantic partners, low-level state secrets) and reversals charged with distinctive Stoppard classical references, and love and regard for the generative power of rock and pop.

Hapless, music-obsessed Jan (Jacob Fortune-Lloyd), with an origin story similar to that of the playwright himself (Czech, but coming of age in England) and Max (Nathaniel Parker) his Marxist, materialist Cambridge professor, roar at each other, diverge then drift back together over the course of some 20 years, along with the political fortunes of Jan’s country. When Jan returns to Czechoslovakia in 1968, as Soviet tanks arrive, to surveillance, imprisonment, and the repressed underground rebellion of subversive group The Plastic People of the Universe, Max’s own world is threatened by his wife Eleanor’s (Nancy Carroll) cancer.

Fortune-Lloyd does a good job of showing us how Jan grows into himself over the years, both more and less certain as an older man who has suffered, while Parker’s Max is an upright island, seemingly the only Marxist academic in an England increasingly going to the dogs, matched in fury by Carroll’s very funny and warm Eleanor. The production sings in her refutation of her husband’s materialism in the face of her sickness: she and her mind are still there, she protests. Carroll also plays Eleanor’s daughter, the former flowerchild Esme, less well-sketched though charmingly chaotic, who has been drawn to Jan since she was a teen.

All the actors are strong, though some are limited to only a scene or two each: it’s hard to imagine many playwrights living their Monsterist dreams similarly in this funding landscape. They’re somewhat hamstrung by the choice to produce Rock ‘n’ Roll in the Hampstead’s Upstairs in traverse; though Anna Reid’s earthy-toned set marries outdoors and inside, Cambridge and Prague, the actors feel somewhat marooned, with some floundering vocally in the space. Sounds can be heard from offstage and there’s echoing: it sets everything at a considerable distance that must be overcome for the comedy and speed necessary for such a play, and as a result, much characterisation seems to get increasingly and distractingly bigger.

Unfortunately, there’s no getting away from a sedentary feel to this production: it drags less in the second half, though it also feels increasingly unsure of what it’s saying. The blasts of rock and pop and dancing in the scene transitions feel less a striking choice and more an indictment of the same energy lacking in the scenes themselves. Brenock O’Connor’s elusive Piper is a welcome addition to some sequences, strumming away, but otherwise, there’s a faithfulness and lack of willing to experiment here which serves the production less well.

It doesn’t feel as if Raine gets really under the skin of what’s happening. Anna Krippa’s first scene as Lenka, Eleanor’s Greek student with an eye for Max, helps to activate the rest of the play – it feels like the audience sit up and shake themselves – and tie the threads of art, love and politics together. But though we follow the emotional truth of what passes between Max and Jan, the weaving of Stoppard’s layers elsewhere doesn’t work as it might, as the clarity of the history and agents the actors are referencing doesn’t come across. It feels hurried through, that we’re on firmer ground when dealing with Sappho, Syd Barrett, or the relationships. “That’s the story, I’m afraid,” Jan is told when he complains journalists never want to write about the music of Plastic People of the Universe, just the dissidence. There’s the feeling that the play is straining against the same limitations.

Though this Rock ‘n’ Roll sits fairly well at the Hampstead, perhaps a different take on the play could’ve given it a vibrancy lacking here. Does its programming here and now speak to a slip into further vague political quietism? We’re all travelling the same direction really, Stoppard seems to say. He can’t help his sentimentalism, though, animating his reluctant or would-be revolutionaries with real, difficult to resist feeling. His characters with convictions sing, and there’s a hell of a kiss.