Richard II at Bridge Theatre review – Jonathan Bailey is a vicious monarch

Nicholas Hytner’s production continues until 10 May

Of all Shakespeare’s heroes, Richard II is the one who most clearly presents himself as an actor. He’s always trying on roles like clothes, wearing the mantle of kingship, seeing how it looks and then throwing it off – seemingly on a whim.

It’s a role ripe for star casting: Eddie Redmayne, David Tennant, Ben Whishaw are all recent Richards. Now Jonathan Bailey, hot off the back of Bridgerton and Wicked, has his shot at the part in a new production by Nicholas Hytner, which turns a history play, described as a tragedy, into a thriller.

The most compelling quality of the staging – driven on by a Hitchcockian score by Grant Olding – is the way that it treats the unfolding events not as historical inevitability, but as if they are changing moment to moment. From the start when Bailey’s petulant, self-obsessed king first confronts Royce Pierreson’s bullish Bullingbrook (listed according to first quarto spelling) in a scene where a lot of angry noblemen are getting very cross and shouting at each other, while flinging down their passports, it’s never quite clear what is going to happen next.

On Bob Crowley’s bare thrust stage, which uses platforms to bring up occasional furniture, and played in plain modern dress, Richard’s fitted tailcoat and tie pin contrast sharply with the upstart’s casual gear. As he peacocks for approval, there’s a sense that he is testing the limits of his power, never quite in control of his own emotions. Surrounded by hangers-on, he sniffs cocaine and waits for their approval for his edicts; they warily gauge his mood.

It’s not just the characters who never quite know what he is going to do. The audience, roped in as a wider populace, are also held in suspense. In historian Helen Castor’s excellent programme essay, she explains how the real, historic Richard was obsessed with the sacred state bestowed on him from the moment he ascended the throne as a child of ten, but never drew the right lessons from the situations he found himself confronted by.

Hytner and Bailey reflect that sense of absolute power tinged by temperamental instability. In the scene where Richard is holed up in Flint Castle, and Bullingbrook (soon to be Henry IV) is outside the walls, the attackers wheel on stage a huge rocket launcher, while Richard appears on the balcony, dressed in saintly white. At one moment he is defiant, and they look nervous, the next he’s in tears and about to give up. It could go either way.

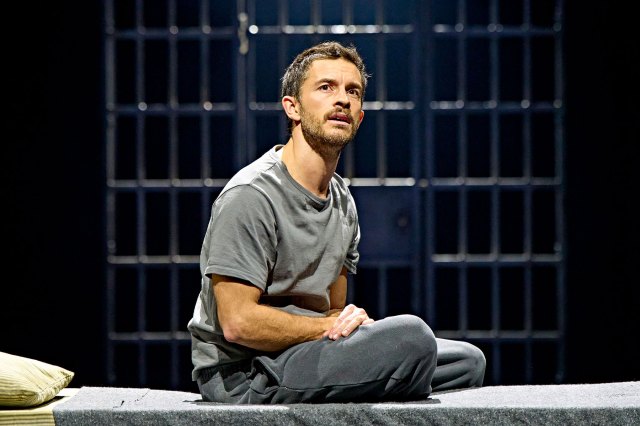

It’s the same in the famous deposition scene, where the two antagonists hold the golden loop of the “hollow crown” between them, circling one another warily as the pretender asks Richard whether he is prepared to abdicate. He vacillates, at one moment agreeing and the next withdrawing his offer. Bailey plays each ‘ay’ and each ‘no’ differently, waspish, regretful, petulant.

“Let us sit upon the ground and tell sad stories of the death of kings”, isn’t a poetic meditation as much as a bout of wallowing self-pity, delivered whilst sitting among the literal rubbish of a ruined kingdom. Even as he faces death, when Richard is usually deemed to have discovered the compassion and humanity that has hitherto eluded him, Bailey is angry when the music he hears is played out of time.

It’s a bravely vicious performance, leavened with wit and humour and yet also deliberately mannered and alienating. This riveting and not always comfortable portrayal is absolutely matched by Pierreson, who cleverly charts, with the smallest inflections of head and eye exactly how difficult it is to make policy on the hoof.

Hytner mirrors the various crises that beset them, sitting Pierreson at the same desk Bailey once occupied and letting the difference register. He surrounds them with a subtle and differentiated set of very contemporary courtiers, in hoodies and anoraks, with Michael Simkins’ Duke of York constantly burdened by the responsibilities placed on him, like a grumpy retiree doing everything for a quiet life while Christopher Osikanlu Colquhoun’s ambitious Northumberland is silky and ruthless. Badria Timimi is an eloquent Bishop, whose principled stand for an anointed king earns Bullingbrook’s forgiveness, while Amanda Root adds comic heft as the Duchess of York, on her knees in wellies.

It’s propulsively driven, and often surprisingly funny, wheeling along with an absolute confidence. It’s been a long time since Hytner’s directed a history play and it feels worth the wait.