© Nobby Clark

Oblique wordplay, broken sentences, meanings just out of reach. The first act of David Mamet's 1992 two-hander about education and power lulls the watcher into a false sense of security. There's something difficult to grasp about the interrupted, back-and-forth dialogue between John, a professor at a university and his student Carol, but what exactly? It seems to be a case of a benevolent teacher helping to support a struggling student; an awkward, angry and confused young woman being transformed into a budding, confident intellectual.

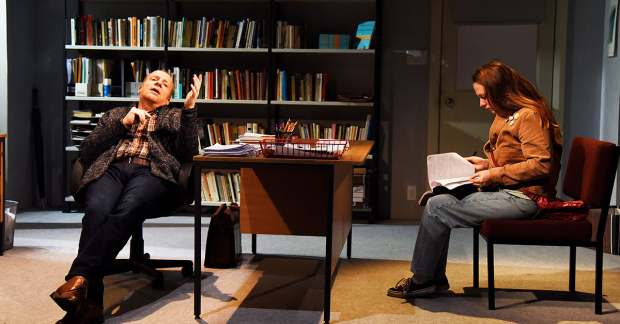

"Surprise is a form of aggression", says John at one point, and both surprise and aggression burst at the seams of this play. Each of Oleanna's three acts bring a new perspective on the previous; a new interpretation that's both entirely true and entirely false. Everything is played out in John's university office, on Alex Eale's beautifully 90s book shelf-covered set featuring classic clunky phone and computer monitor. The audience is witness to events that are reported afterwards to unseen third parties: John and Carol's view of what happens differs significantly, but what about ours?

This question is one of the key, most clever and most unsettling elements of Mamet's script which makes the audience privy to a situation that usually happens only behind closed doors. Lucy Bailey's sleek, smart production plays on the guilt we feel as passive observers. It's only by act three that what we see becomes undisputable.

There's a lot going on in the 80 minutes run time, and it's not just about that oftentimes murky relationship between pupil and teacher, it's also about who has access to power, why, and whether that's right. There's no question Carol undergoes a metamorphosis; both characters do. And by the third act you begin questioning what you felt about the first, where a teacher on the verge of tenure at his university argues against education for all and encourages a vulnerable student to return back to his office regularly so he can take time to guide her through his ideas on a one-to-one basis.

Bailey's direction hits right at the heart of Mamet's intentions, leaving us feeling bewildered and more than a little uncomfortable. Her two actors, Jonathan Slinger as John and Rosie Sheehy as Carol, are very good, their contrasting energies playing off each other with a real intensity. Their turns help to make our interpretation of what we see on stage unstable. Neither of the characters are likeable, neither of them are easy to read, and there's so much going on underneath each performance that it ensures we leave the auditorium our heads whirring in thought.