Review: De Profundis (Vaudeville Theatre)

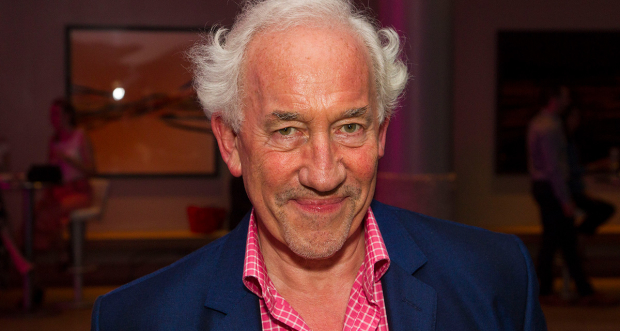

Simon Callow stars in Frank McGuinness’s adaptation of Oscar Wilde’s letter, written while incarcerated in Reading Gaol

© Dan Wooller for WhatsOnStage

In 1895, Oscar Wilde, then 41 years old, was incarcerated for gross indecency. It is largely seen as the end of Wilde's career – the moment his reputation was left in tatters and he had to endure two years of intense punishment within a variety of penal institutions. It was while imprisoned in Reading Gaol that he decided to write this De Profundis, an exceptionally long letter addressed to former lover Lord Alfred Douglas ("Bosie"), . It's that letter which, as part of Dominic Dromgoole's Wilde season in the West End, has been adapted by Frank McGuinness into a monologue, performed by stage veteran Simon Callow.

Sat on a lonely chair against a darkened Vaudeville stage, it's hard to imagine many performers being able to pull off what Callow does with the text. His face is a constantly moving swirl of emotions as he speaks Wilde's prose, portraying everything from thinly veiled anger to despair to, at times, rampant narcissism. Callow, largely marooned in a sea of shade, pulls off the difficult feat of never feeling too static, weaving through the text and the constituent emotions.

McGuiness reverently reassembles and crops the 50000-word letter into a more cogent 90-minute experience, using Wilde’s relationship with Bosie to provide a neat through-line and narrative thread. We see Wilde being seduced by his young compatriot, the wars between the writer and his lover’s father the Marquess of Queensberry, and his eventual imprisonment. If anything, the performance loses some of the intellectual’s sardonicism and thoroughness by trying to create a more neat structure – downplaying, for example, the religiousness of the original piece.

But for the most part, McGuiness lets Wilde’s text stand on its own two feet, creating a vivid depiction of a man coming to terms with a great sense of loss, while still burning with the desire to write and reason. Wilde furnishes his tale with paradox and ironic complexity – while he lambasts the infantilism of Bosie (Callow dripping with scorn when he delivers the word ‘undergraduate’), he also reveres and cherishes his infant son Cyril, taken from him by the law.

Intriguingly, McGuinness’s chosen passages see Wilde write largely in the passive, with acts committed unto him rather than by him. It’s an active attempt to disprove any sense of agency, for Wilde to justify his actions, and present himself as a figure caught out in a space between romantic intellectualism and intellectual romanticism.

Wilde was a man who, though largely playing life as a comedy, ended it in the midst of great tragedy. One memory stood out among others – Wilde recalls how, as he was being led to prison, he was forced to stand on the platform of Clapham Junction station, where he was laughed and jeered at by the crowds around him. As De Profundis recalls, "for a year after that was done to me [Wilde] wept every day at the same hour and for the same space of time".

De Profundis has now completed its run, but the Wilde season will continue with Lady Windermere's Fan at the Vaudeville Theatre from 22 January to 7 April, with previews from 12 January.