At the End of Everything Else (Unicorn Theatre)

This delicate and imaginative tale tackles pollution with eco power

© Manuel Harlan

As we finally accept the absolute certainly that our world is under threat from global warming and pollution, Mark Arends‘ play offers a hopeful message that the earth may find itself in better, more careful hands once today’s children are old enough to take charge. Surely by then we’ll have come up with a carbon-neutral lifestyle?

The writer and director was inspired to create At the End of Everything Else after reading about the monstrous plastic island that floats in the Pacific ocean, wrecking sea life with its landmass of discarded bottles, wrappers and cartons.

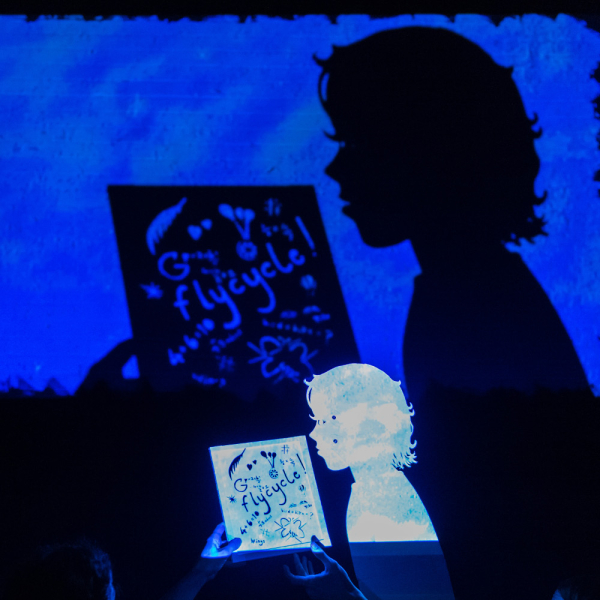

He wonders how this ecological nightmare can ever be resolved, but in the meantime, Arends and company demonstrate their own impressive commitment to sustainable living by powering the entire performance themselves. They pedal steadily on bikes throughout the 45-minute show, generating enough electricity to light the stage, the auditorium, lanterns and a variety of projectors. This inspired engineering feat is thanks to Colin Tonks from Electric Pedals.

Instead of using actors on stage, animators John Horabin and Penny Layden tell the story through an intriguing mix of stop-frame animation and shadow-puppet silhouettes, projected onto the white-painted back wall of the theatre.

The heroine, little Icka, grieves for the mother she never knew. When she adopts an orphaned bird, Icka discovers co-operation and working together can conquer problems that appear insoluble. Along the way she also comes to terms with the fact that her mother will never come back, but accepts that she and her Dad can find happiness again.

Some of the effects the animators create are very beautiful and include the charming little bird Tito, a winged bicycle and a fantastical trip around the world, complete with landmarks like the Eiffel tower and Taj Mahal. These visual feasts are a delight to watch, and they’re accompanied by Mark Arends’ tender original score.

It’s hard to quibble with such a well-intentioned and imaginative piece of theatre. But for a young audience, the story becomes convoluted and underpowered as it progresses into the fantasy sequences, and its eco-message blurs.

The concept of the plastic island in the Pacific isn’t made entirely clear, especially as in Icka’s mind the island is strongly linked to her lost mother, who visits in dreams and begs her daughter to release her.

But Icka and Tito’s final efforts to lift the rubbish out of the ocean are ably supported by children from the audience, who hurry eagerly on stage to do their bit towards the required pedalling and wing flapping.

The commitment and inspiration that shine through this production are not in question. But a clearer, stronger narrative would lift it into another sphere.