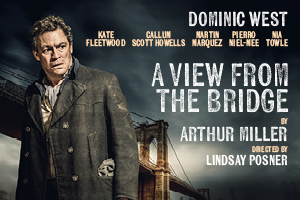

A View from the Bridge with Dominic West in the West End – review

Lindsay Posner’s production runs at Theatre Royal Haymarket until 3 August

Arthur Miller set himself up to be compared with the greats. In A View From the Bridge, written in 1955, it’s the fate-driven tragedy of Greek drama he emulates, framing the action with a chorus in the shape of a lawyer narrator who sees the story of a working-class longshoreman in Brooklyn as worthy of comparison with the fall of kings.

Some of these devices seem old-fashioned and heavy-handed now, but A View from the Bridge has survived because of its insight into the dynamics of emotional relationships. And it offers an absolutely cracking central role for any actor as Eddie Carbone, a man who sees himself as honourable but is undone by his unacknowledged passion for his niece Catherine.

It hasn’t been seen on the London stage since Ivo van Hove’s ground-breaking production in 2014, which stripped away the realistic setting and concentrated on the impact of that relationship. Lindsay Posner’s new production, imported from Bath’s Theatre Royal, is less insightful, but still packs a punch and gives Dominic West a chance to follow in the footsteps of actors such as Michael Gambon and Mark Strong in the central role.

West is good at suggesting the rough life of the streets, as he showed in his career-shaping performance as Jimmy McNulty in The Wire, and here he convinces as a man who lives by his strength and his reputation in the closed world of the docks. He mines the humour in Eddie’s simple attitudes, his sense of himself as a good provider.

But his jutting jaw and constantly working mouth suggest suppressed emotions that he cannot examine or express. He’s proud that he helps his wife’s Italian cousins illegally come to find work in America; this is a world whose codes he understands. But when a relationship develops between Rodolpho, one of the “submariners”, and Catherine, he is utterly unable to comprehend why he feels the “boy ain’t right”. Roaming the stage like a bull, his bonhomie vanishes and his anger rears as he precipitates his own tragedy.

The performance, like Posner’s direction, is relatively straightforward. Peter McKintosh’s lowering tenement set, where only Paul Pyant’s lighting distinguishes between internal and external scenes, crowds on the characters just as surely as their poverty and their struggle to get by.

It’s interesting watching the play at this distance to note how Miller writes about men but makes the women the tellers of truths. Everyone except Eddie knows what is happening; they point it out to him. He just can’t accept that image of himself. Kate Fleetwood gives a fine, damped-down performance as Bea, the clear-sighted wife and Nia Towle is gloriously open as Catherine, growing from child to adult in the course of the play. As her love, Callum Scott Howells matches her attractive tolerance, and the scene between them, when they discuss whether he is marrying her only for the sake of citizenship, is perhaps the most powerful of the night.

Aspects of the drama – the desperation of the migrants, the shrinking nature of poverty and a man’s inability to examine his own nature – resonate, even if the specific circumstances have dated. People still gasp when Eddie commits the ultimate betrayal. It is a gripping story, well-told. Just as Miller intended.