Review: "Master Harold"…and the Boys (National Theatre)

© Helen Murray

The great South African playwright Athol Fugard wrote Master Harold…and the boys in 1982, when apartheid was still alive and well in his homeland, where the play was banned. It is based on an incident in his own childhood in 1950. Yet decades later, in a changed world, its message about the corrosive effects of racism on human relationships feels as searing and urgent as it did when it was first performed.

It's a classic example of a play where a single room – in this case, a tea shop in Port Elizabeth, beautifully evoked with a rain-soaked skylight and a pattern of wooden tables designed by Rajha Shakiry – stands for an entire world. Here we meet Willie and Sam – the boys of the title – waiters in the café, practising their moves on a quiet rainy afternoon for a forthcoming ballroom dancing contest.

They seem comic, but they are deadly serious, moving with grace and purpose in their attempt to win the competition, Willie's efforts somewhat undermined by his tendency to beat up his girlfriend. "It takes the romance out of ballroom," remarks Sam, wryly. They are soon joined by a real boy, but their master in the distorted values of apartheid, young Hally, son of the owner, whose relationship with them is a disturbing mixture of unexamined superiority, and needy affection.

When he learns over the telephone that his father – crippled and a bitter drunk – is about to come home, the swirl of his emotion overwhelms him and he turns on the men who have provided him with kindness and support. The effect is shocking; the temperature drops to zero and the audience gasp. Director Roy Alexander Weise modulates the mood on a pinhead; each beat of the changing moods is wonderfully caught, through early joshing, to deep pain, to its final, emotional conclusion.

One of the many extraordinary qualities of the play is how brutally honest Fugard is, looking back on his own behaviour with shame and understanding; another is the way that sense of shame – and by implication its effect on the white population of South Africa – becomes its theme. Hally is an extraordinarily critical self-portrait, a boy who talks of equality and human rights but is so bound up in his pompous narcissism that he can't see what is happening around him. It is the self-centredness of youth, of course, and Fugard gives his young self that pass, but it is also a devastating analysis of unkindness and assumption.

Against Hally's casual racism and assertion of privilege, he sets Sam and Willie's world of service alleviated by their visions of ballroom glory. The scene in which Sam and Willie explain with dazzling eloquence and mounting excitement why they love dancing soars. "It's like living in a dream about a world where accidents don't happen," Sam explains, wistfully.

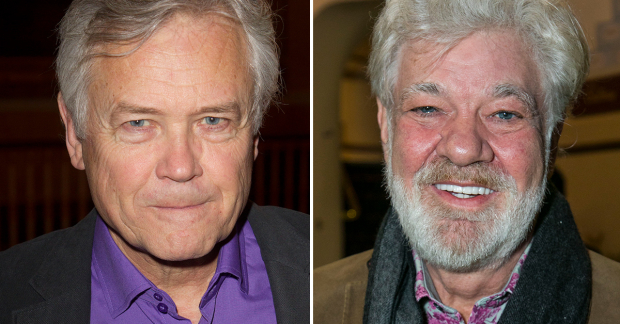

Lucian Msamati, natty in white jacket and black pumps, delivers the words like a poem of possibility. He is such a wonderful actor, really one of our very best, and he is magnificent here, quietly registering every moment of feeling, watchful and careful when he must be, expansive when he can, and finally, devastatingly, trying to behave in the most dignified way possible when the ground on which he has taken his principled stand is pulled from under him.

As the slow-witted and large-bodied Willie, Hammed Animashaun is equally powerful, capturing the contradictions of this big-hearted man who is fuelled by anger and fear, yet is willing to sacrifice his last sixpence to hear a song of wonder. Between performances of this stature, it's hard for Anson Boon's gauche, gangling Hally to make his mark; this is his stage debut. He catches the grating Afrikaner accent and the shocking drops of prejudice that pepper his conversation, but nerves perhaps prevent him from finding the shades of feeling that would help him to mine the character's soul.