British theatre is in danger of cutting itself off from Europe

© Siebbi, Nicolas Genin

To Rome, last month, for the Europe Theatre Prize – a biennial festival built around a set of presentations. Orchestrated by critics from across the continent, it seeks to celebrate the artists, companies and institutions that have changed and, indeed, are still changing the art-form around Europe. Given Brexit – a frequent topic of conversation, not to mention consternation – it felt like a pertinent place to be.

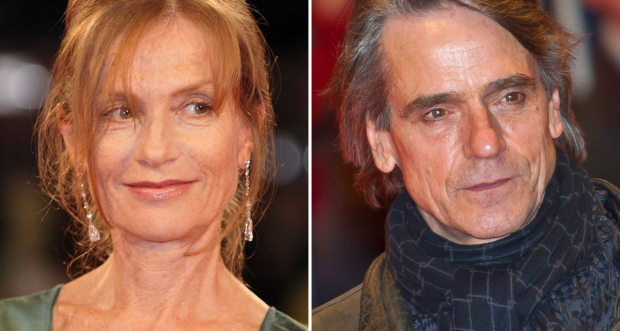

Britain, as it happens, had a winner: Jeremy Irons was honoured alongside his fellow actor Isabelle Huppert. They join an illustrious list of individuals, that includes Pina Bausch, Peter Brook, Robert Wilson and the late Harold Pinter, but I couldn’t help thinking Irons an odd choice. The intention, I imagine, was to redress an absence of performers in the prize’s history. Of the 15 previous recipients, only one, the French film star Michel Piccoli, was an actor.

Actors can only gain a continent-wide reputation through film

Irons is a fine actor – no doubt about that. He has a mercurial quality, as capable of carrying off majesty as he is malevolence. (Witness Scar in The Lion King, a voice like shrapnel and silk, then cast the man as Claudius.) It’s also true that Irons transcends the role of actor. More than most, he has an artist’s inclinations and the word that kept cropping up was 'vagabond'. He is an aesthetic nomad; a rover who follows his interests and allows his interest to be piqued. "The idea of a career seems to me like a prison", he once said. It’s what makes him watchable – engaging because he is himself engaged. Irons seems to toy with his parts, playful and inquisitive. He relishes a challenge.

But is he, I wonder, worthy of a theatre prize? For all his talent and his manifold charisma, Irons has hardly changed the face of theatre in this country – let alone, on this continent. There was Godspell, yes, and his Tony Award-winning turn in Tom Stoppard‘s The Real Thing, but this is an actor who went a whole 18 years without stepping on a stage. Around that are a couple of stints at the RSC, a fitful flurry of roles in recent years, but little that has pressed itself into stage history. Actors can: Anthony Sher has, Judi Dench and Ian McKellen has, Irons hasn’t. (Long Day’s Journey Into Night, due in the West End next month, is unlikely to change that.)

Our theatres have all but stopped touring to mainland Europe

It’s telling that his biography in the prize programme began by detailing an extraordinary screen career. Theatre pops up almost as an afterthought – a footnote to Oscars and Emmys, to The French Lieutenant’s Woman, Brideshead Revisited and, er, Die Hard With A Vengeance. True, he brings an eye-catching theatricality to the camera that always leaves a lasting impression, but when a seven-strong panel sat down to discuss his career and his character, only one of them had worked with him in theatre. Indeed, we heard more about his fondness for restoring old Irish castles than about his propensity for stage acting.

The point, though, may be that actors can only gain a continent-wide reputation through film. Huppert, for her part, has always been a theatrical creature and, alongside her singular screen career, she has always sought out daring directors to work with: Robert Wilson, Luc Bondy, Benedict Andrews and more. British audiences got a glimpse of her last year. Even so, as with Piccoli and Irons, her reputation reaches across Europe (and the word) via celluloid.

Look down the list of previous winners and something stands out. Either an artist leaves something concrete that can travel without them – Pinter’s plays were produced across Europe, much to his own frequent amusement – or their work itself travels. Peter Brook and Pina Bausch, Robert Lepage and Patrice Chéreau – these are world-renowned artists whose shows span the globe, let alone the continent.

In that, Britain’s directors are in danger of missing out – and with that, British theatre risks cutting itself off. Our theatres have all but stopped touring to mainland Europe, lured instead to the bright lights (and big bucks) of Broadway, the English-speakers of Australia and New Zealand or, in the RSC’s case, the cultural diplomacy of China. We are, however, in danger of forgetting about our closest neighbours.

Could a Robert Icke or an Ellen McDougall show be mounted for such a festival?

That wasn’t always the case. The National was the first western institution to cross into Russia during the Cold War. Shows toured to Eastern Europe and Scandinavia, as well as the major western European theatre cultures. Blame the ease of long-haul travel and transport, perhaps, but this sort of cross-cultural exchange was once deemed valuable.

In Rome, I saw the work of two German-based directors, Susanne Kennedy and Yael Ronen, both recipients of this year’s New Theatrical Realities Prize. Their shows were both singular and astonishing. Kennedy turned Jeffrey Eugenides’ The Virgin Suicides into a strange study of teenage girls, the four sisters represented by manga-like mannikins dolled up like Hindu gods. Ronen, meanwhile, showcased a puckish, punkish cabaret devised with actors of Romany descent that challenged received stereotypes and stood up to all too real, extant prejudices.

The point, though, is that German theatre was being presented in Rome – a product, perhaps, of the rep system. Earlier in the week, the festival had seen shows by Estonia’s NO99 (one third of Three Kingdom’s creative team) and the Russian designer-director Kirill Serebrennikov, recently detained on bogus fraud charges.

Could a Robert Icke or an Ellen McDougall show be remounted for such a festival? I sincerely doubt it. Scottish institutions are well represented – the Traverse and Vicky Featherstone’s inaugural National Theatre of Scotland programme have both shown work at past festivals – but most of the game-changing English artists recognised have worked independently, either touring like Cheek by Jowl and Forced Entertainment or employed overseas like director Katie Mitchell and Deborah Warner.

European imports have had a tremendous impact on British theatre in the last decade. For that to become a two-way relationship, British theatres have to tour to Europe. We can’t simply rely on playwrights and film stars.